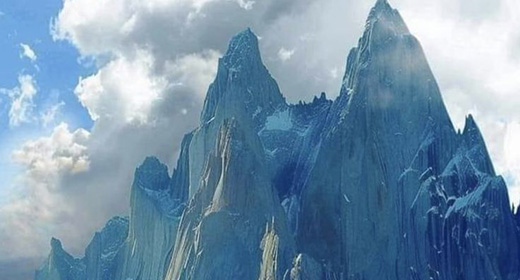

In the late 1960s, a gorgeous stretch of beach in Ha’ena State Park was the site of a hippy haven called Taylor Camp…

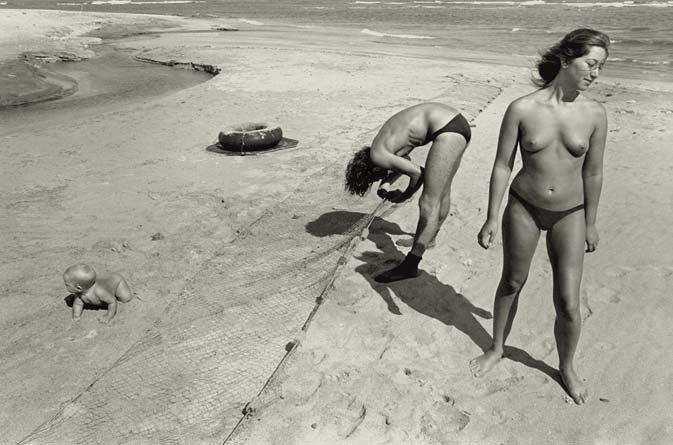

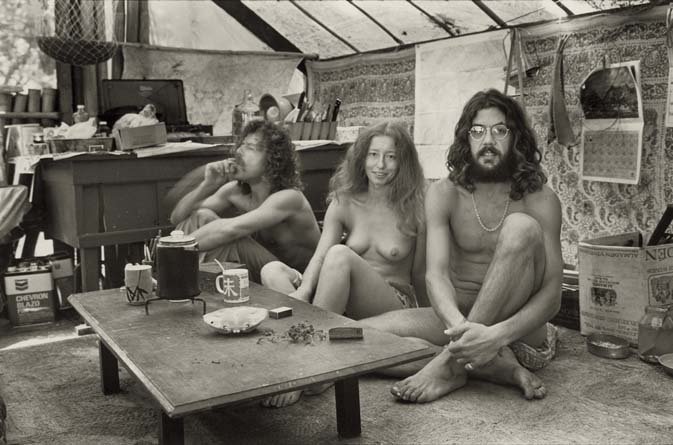

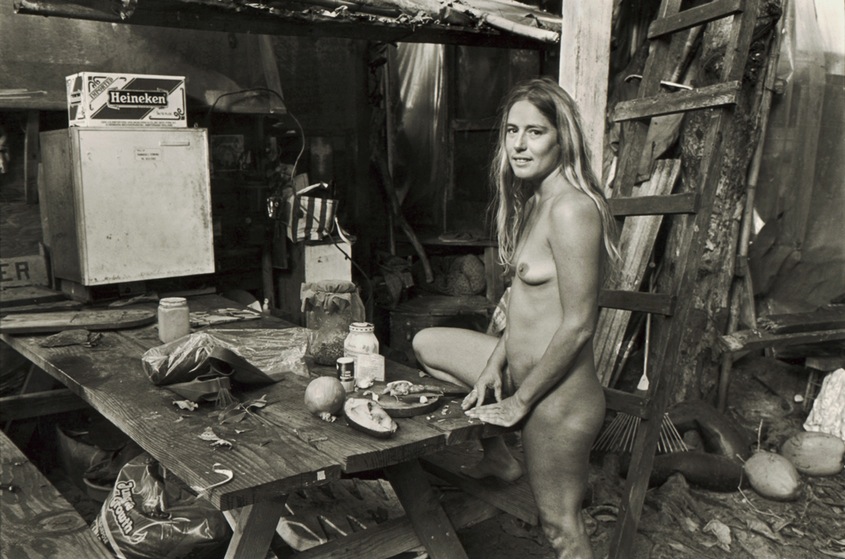

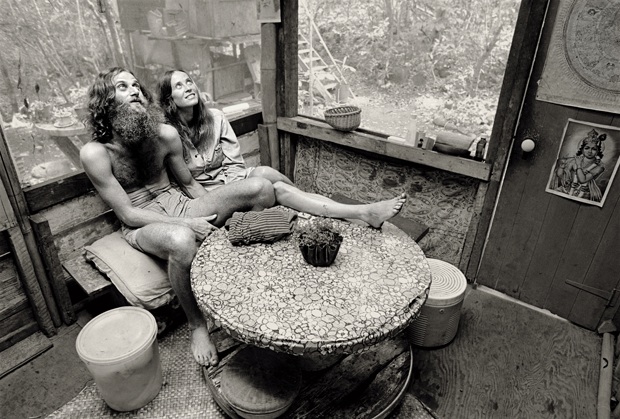

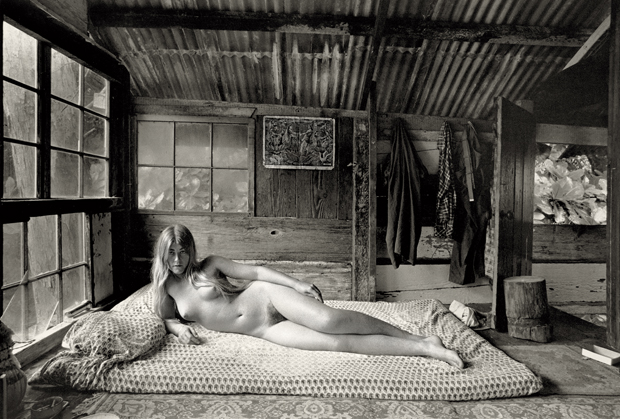

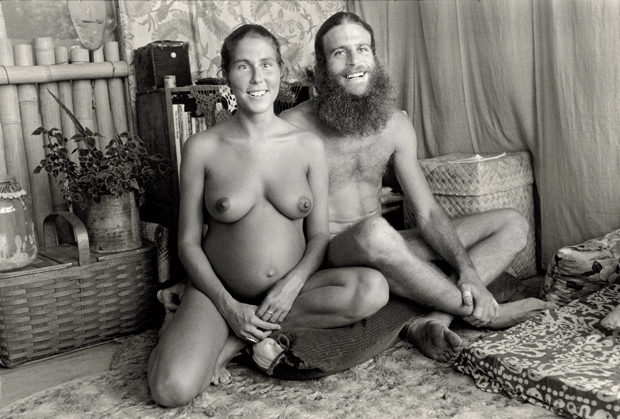

Anti-establishment all the way, clothing was optional and decisions were made according to the “vibes”. It was the ultimate hippie fantasy.

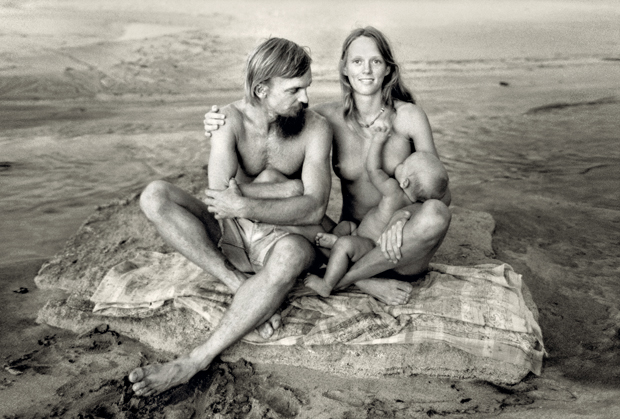

A band of young people came to the same place in 1969, most of them refugees from strife-ridden college campuses and Vietnam War protests. They drifted in from all over the mainland, looking to turn down the volume at the end of the blaring 1960s and pitched tents in a North Shore park, playing beach volleyball in the buff and smoking marijuana, activities that ultimately got them evicted.

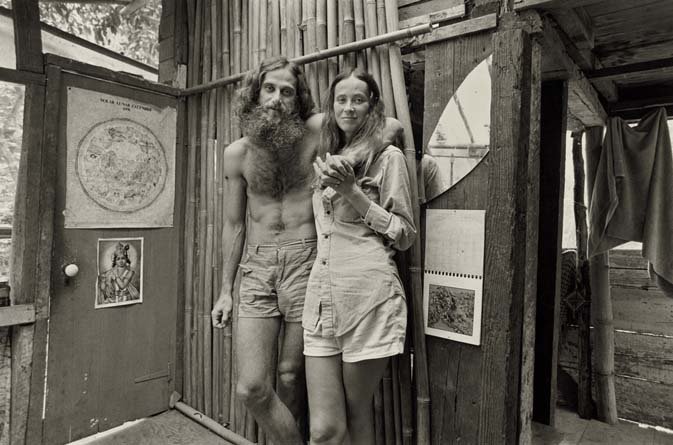

Enter Howard Taylor, brother of movie star Elizabeth, who bailed them out of jail and invited them to settle on a beachfront property he owned that had just been condemned by the state. His kindness was also an act of revenge because the state would have to deal with the squatters before they could turn the place into a public park. “It’s your land and they’re now your hippies,” he told officials. After joining the campers for Christmas dinner in 1972 with his celebrated sister, Taylor left them to their own devices.

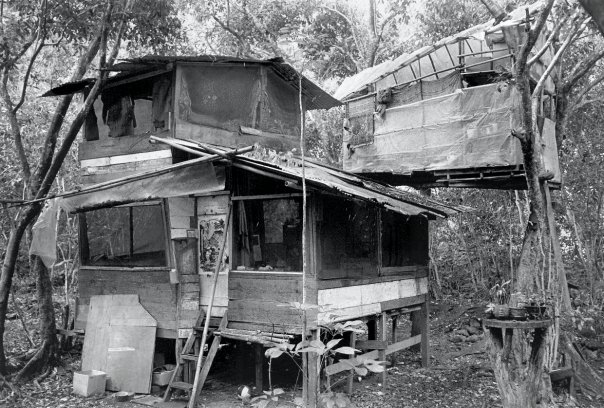

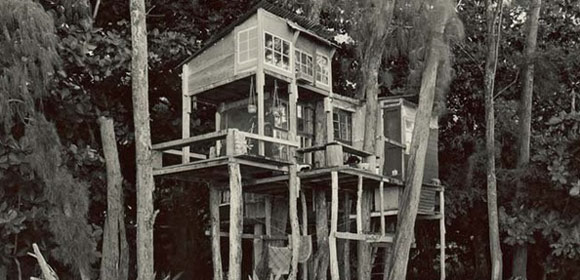

The society dropouts started building their beach-front tree houses with bamboo, scrap lumber and salvaged materials. The “flower power campers” were living out their utopian dream without any restrictions or supervision.

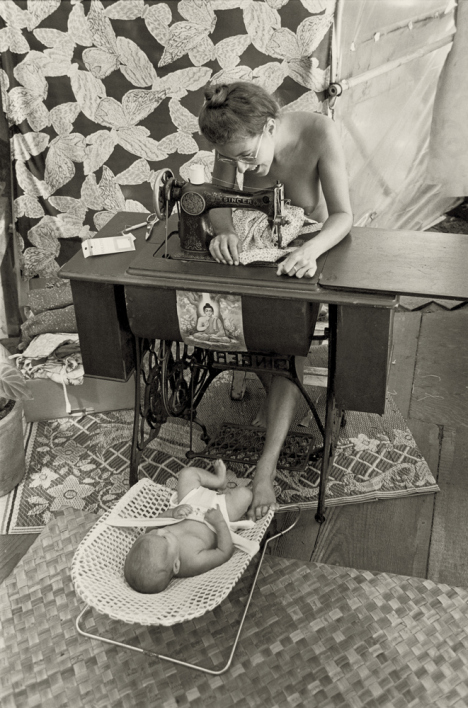

They lived off the land (and the occasional food stamps) and fished and recruited a medic and a midwife. The children went to school and even got a ride from the school bus after some campers convinced the driver to include Taylor Camp on his route. Word of the village spread far and wide and more hippies, surfers and troubled Vietnam war veterans arrived to start a new life in the ungoverned beach community.

Taylor Camp stood for eight years, until in 1977 it was razed to the ground. As the state government began to close in, the community enlisted the help of Legal Aid attorney Max Graham and his assistant JoAnn Yukimura, who would go on to become both Wehrheim’s wife and the country’s first Japanese-American woman mayor. Although the evictions were delayed over a few years, most the campers were ultimately persuaded to abandon camp of their own volition, relocating to different parts of the island and country. The few who stayed behind were robbed and beaten by local troublemakers until they were carted out by the authorities and every last remnant of the camp was burned. A mother and her infant were among the few who remained until the end.