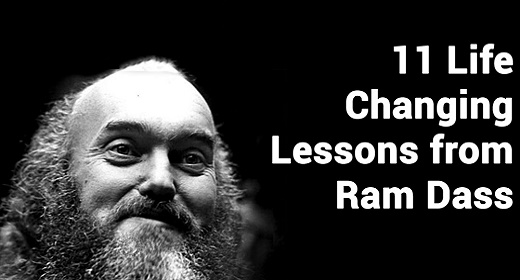

by Amishi Jha: Our ability to pay attention is unreliable when we’re under stress…

In her new book Peak Mind, neuroscientist Amishi Jha explores cutting-edge research on elite soldiers revealing how mindfulness training protects our attentional resources, even in the most high-stress scenarios imaginable.

You are missing 50% of your life. And you’re not alone: Everyone is. I say this confidently, even without knowing who you are, or how your brain might be different from the last one we tested in my lab at the University of Miami, where I research the science of attention and teach cognitive neuroscience courses.

Over the course of my career as a brain scientist, I’ve seen certain universal patterns in the way all of our brains function—both how powerfully they can focus, and how extraordinarily vulnerable they are to distraction—no matter who you are or what you do. I’ve had the opportunity to peek inside the living human brain, and I know that at any given moment, there’s a high probability that your mind just isn’t here. Instead, you’re planning for the next item on your to-do list. You’re ruminating on something that’s been bothering you, a worry or a regret. You’re thinking about something that could happen tomorrow, or the next day, or never. Any way you slice it, you’re not here, experiencing your life. You’re somewhere else.

Mental time travel is one of the biggest culprits degrading our attention. We do it all the time. We do it seamlessly. And we do it even more under stress. Under stress, our attention gets yanked into the past by a memory, where we get stuck in a ruminative loop. Or we may get launched into the future by a worry, leading us to catastrophize on an endless number of doomsday scenarios. The common denominator is that stressful intervals hijack attention away from the present moment.

Mental time travel is one of the biggest culprits degrading our attention. We do it all the time. We do it seamlessly. And we do it even more under stress.

This is how mindfulness first entered my lab as a possible “brain-training tool.” I wanted to know whether training people in mindfulness exercises could help them be more effective in high-pressure situations. Our basic definition of mindfulness was this: paying attention to present-moment experience without conceptual elaboration or emotional reactivity.

I wondered if training people to keep attention in the here and now, without editorializing or reacting, could serve as a kind of “mental armor.” I wanted to answer this question: Could mindfulness training protect and strengthen attention?

To find out, we set our sights on one of the most high-stress, high-demand populations: the military.

Can Mindfulness Stabilize Attention?

“This is never going to work.” That’s what then-captain Jason Spitaletta said to me as we walked onto the Marine Corps Reserve Center in West Palm Beach, Florida. He sounded good-natured about it. He smiled when he shook my hand and cheerfully told me our study was probably doomed. Marines, he said, were just not going to go for it. Mindfulness wasn’t something they’d invest in—it was too “soft” sounding. (This was 2007—it was very new to everybody back then.) Nevertheless, Captain Spitaletta and his co-leader Captain Jeff Davis had agreed to host our study on mindfulness and attention. When we’d spoken to Davis on the phone a few months before, he’d seemed skeptical yet open, acknowledging that they needed to try something new.

Spitaletta and Davis appeared exactly the way I figured Marines would look: jarheads. I admit that I had a moment of cognitive dissonance. It was hard to picture these two—stoic, brawny guys in desert camo—sitting and meditating. And if even I had trouble picturing it, military leadership would likely have its own doubts. At this early point in our research, there was no precedent for mindfulness meditation as “cognitive training.” We were going to put this to the test and see what the data revealed. My main goal was to set the conditions for a strong experiment: asking the right questions and selecting evaluation metrics that would be sensitive enough to detect even small changes in attention. With thoughtful planning and luck on our side, we’d get a clear answer, one way or another.

My team and I set up our computers and gave the Marines various cognitive tasks. We also looked at their mood and stress levels. And then, for the eight weeks of pre-deployment training that followed, they were offered a 24-hour program modeled off of the well-established, mindfulness-based stress reduction techniques that had been tested in medical settings, but contextualized for a military cohort. They were introduced to a foundational set of practices: attention to the breath, body scans—practices that entail bringing attention into the present moment, in a “non-editorializing” way. We knew we needed to deliver these practices in a way that would make sense to this demographic so that it would be accessible to them. Their homework: 30 minutes of mindfulness practice every day.

Eight weeks later, we were back to test them again. Some had done the assigned 30 minutes daily on several days, but most did far less. They were all over the place. This was what data from the field can often look like: lots of variability across participants. To plot the results, we split the group in two, based on how much they practiced. Here’s what we saw: While the low-practice group got progressively worse in terms of attention, working memory, and mood over the eight weeks, the high-practice group remained stable. At the end of the training, the high-practice group performed better and reported feeling better than the low-practice group and a no-training control group. What we found echoed some of our earlier studies, except this time under even higher demand: Mindfulness could indeed stabilize attention.

After this phase of our study, the Marines were deployed. When they came back, we retested them. And again, the results were initially a mixed bag—nothing was reaching statistical significance. The group was small; some members had dropped out of the study, left the military, or moved on to a new post. Many had stopped doing the training practices during deployment.

What we found echoed some of our earlier studies, except this time under even higher demand: Mindfulness could indeed stabilize attention.

Still, one pattern stood out. When we looked at those who had been in our low-practice group at pre-deployment, a subset of participants actually performed better than before they left. This result contradicted the earlier data and made no sense—why were they performing so well? After all, even before they were deployed, they’d done minimal practice compared to the others.

Basically, this low-practice group had turned themselves into a high-practice group on their own. Mid-deployment in Iraq, with what I can only imagine were unpredictable schedules and very demanding circumstances, they’d taken it upon themselves to do more mindfulness practice, because it was blatantly apparent to them what a difference it made.

Now, it’s important to note that this study—our first trial run of delivering mindfulness training in a military setting—was promising. Still, it didn’t produce stunning results—it was small, and the data were variable. But even though the results were modest, the implications were huge. First: Mindfulness-based training could be introduced to high-demand groups to protect attention. And second: It wasn’t a situation where you could say “any exposure to training is helpful.” It required regular practice to benefit.

We had right in front of us living, breathing proof that mindfulness training created a kind of “mental armor” that could effectively protect individuals’ attentional resources, even in the most high-stress scenarios imaginable.

The Minimum Effective Dose of Mindfulness Meditation

Today, contemplative neuroscience labs, like mine, are bringing people into the lab to practice mindfulness exercises while lying comfortably in a brain scanner. What are we finding? During mindfulness practice the brain networks that are tied to focusing and managing attention, noticing and monitoring internal and external events, and mind-wandering are all activated. And when participants go through multiweek training programs, here’s what we see over time: Improvements in working memory. Less mind-wandering. More decentering and meta-awareness. And a greater sense of well-being, as well as better relationships.

And the really cool thing is, we see changes in brain structures and brain activity that correspond with these improvements over time: cortical thickening in key nodes within the networks tied to attention (think of this as the brain’s version of better muscle tone for the specific muscles that a workout targets), better coordination between the attention network and the default mode network, and less default mode activity. These results give us insights into the why and how of mindfulness training, insights that we need before we can prescribe the what—meaning what specifically you need to do to achieve these benefits.

The US Army, excited about our early research, asked me how quickly I could scale up to offer it to many, many more soldiers. They wanted me to get trainers out to multiple military bases—fast. The program needed to be time-efficient and scalable. It had to be the lightest, most compact, most impactful

version we could offer. What was the minimum required dose for these time-pressured people, who desperately needed this training, to see results?

My lab set out to drill down to a real “prescription” we could offer people. I partnered up with Scott Rogers; he’d already written books on mindfulness for parents and lawyers, and his style was flexible, practical, and accessible. Looking back at the data we’d already gathered where we’d broken the training group into two smaller groups, a high-practice group and a low-practice group, we hit on something. The high-practice group did benefit. So we zoomed in on them. The average number of minutes per day that this group practiced? Twelve.

We had a number. We took it and designed a new study. We asked our participants (football players this time) to do only 12 minutes of practice. And to help them hit the nail on the head, Scott recorded 12-minute-long guided exercises for them to use. They didn’t have to set their own timers or even push stop—they just had to follow along. We made it as user-friendly as possible.

We ran the month-long study asking them to do their guided 12-minute exercises every day. Once again, we broke the sample into two groups: high practice and low practice. And once again, the high-practice group showed positive results: attentional benefits. And on average, these guys did their 12-minute exercises five days per week.

Then we conducted a study in elite warriors, special operations forces (SOF). We were fortunate to partner with an operational psychologist who worked with SOF who was certified in offering mindfulness-based stress reduction. We trained him to deliver our program. We called the program Mindfulness-Based Attention Training (MBAT). As we had done before, my research team and I packed our laptops and headed to yet another military base, to see if this training actually worked outside of our campus environment and out in the field. We tried two variants of MBAT: one that would be delivered over four weeks, as we designed, and another over two weeks. The results were exciting and promising: MBAT benefited attention and working memory in these elite warriors. The benefits were only there when the program was delivered over four weeks. Two weeks was too short.

Do You Have 12 Minutes to Meditate?

So what does this all mean for you? Mindfulness training does indeed have a dose-response effect, which means the more you practice, the more you benefit. Based on these many studies, what we’ve come to understand is that asking people to do too much, especially those with a lot of demands and very little time, demotivates them. The key is having a goal that is not just inspiring, but possible. Twelve minutes worked better than 30, and five days worked better than every single day. So this is what I want to encourage you to do: Practice 12 minutes a day, five days a week.

For only a little effort and a small investment of time, you can reap an enormous reward. I get asked by many high-achieving, high-stakes professionals whether this practice can be condensed even more. Inevitably, someone will ask: “Four weeks is too long—can’t we just do something in an afternoon?” Or “Twelve minutes is too hard to find in my day, so can I do less?” My answer? Sure you can. And it might benefit you temporarily, like going for a walk can benefit you. But if you want to train for better heart health, you’d want to do more than go for the occasional leisurely walk. In the same way, if you want to protect and strengthen your attention, more is required. We have a growing body of research now. The science is clear. For this to work, you have to work it.

We’re at an exciting moment: We have an amassing evidence base of research. We are learning more and more about what works, and this is going to continue to get better over the coming years and decades. Right now, this is our best understanding of what can help you in terms of your attention and working memory.

What we gain from mindfulness—from the capacity to keep our attention where we need it, in the form we need it—is this fundamental understanding that everything passes. Everything changes. This moment will pass quickly, but your presence in this moment—whether you’re here or not here, reactive or nonreactive, making memories or not—will have ripple effects that expand out much more widely. So the question is: In this moment, can you be present? Can you place your attention on what matters to you? Can you really be here for this experience, so you can feel, learn, remember, and act in ways that make sense in your life, for your goals and aspirations, for the people around you? You don’t have to be born with expertise in these capacities—nobody is. We have to work to hone them. But now, at least, we know how.

Your Three Attention Systems

When we tell someone to “pay attention,” what we often mean is focus. But attention is about so much more than that. Attention is a currency, a multipurpose resource. But our attention isn’t just one single brain system—one that you can direct somewhere to selectively enhance information processing. There are actually three subsystems that work together to allow us to fluidly and successfully function in our complex world.

1) The flashlight = focus

Where you point your flashlight becomes brighter, highlighted, more salient. Whatever’s not in the flashlight beam? That information remains suppressed—it stays dampened, dimmed, and blocked out. Attention researchers call this your orienting system, and it’s what you use to select information.

2) The floodlight = notice

Where the flashlight is narrow and focused, the floodlight (also called the alerting system) is broad and open. Diffuse and ready, it has a broad, receptive stance. You’re not sure what you’re looking for, but you know you’re looking for something, and you’re ready to rapidly deploy your attention in any direction as you respond.

3) The juggler = plan and manage our behavior

The juggler directs, oversees, and manages what we’re doing, moment to moment, as well as ensures that our actions are aligned with what we’re aiming to do. The juggler is the overseer that makes sure you stay on track and that your actions align with your goals—this is also referred to as your

“executive function.”

A Cognitive Training Push-Up: Focus + Notice

Try this focused-attention practice we call a “push-up for your mind.” Here are the basics:

The Warm-Up

Settle in, taking a posture that is alert, steady, yet easeful. Think “upright,” not “uptight.” Feel free to lower or close your eyes.

The Practice

- Focus

Select the sensations of breathing that are most prominent for you. Think of the breath as the “target” for your attention for this practice period. The sensations could be the coolness of the air moving in and out of your nostrils, your abdomen moving up or down, or some other specific sensation tied to your breathing. Now, for the period of practice, focus your attention on these breath-related sensations. - Notice

Notice when the mind has wandered away from your attentional “target.” Perhaps you notice that your focus is now on thoughts, sensations, or memories and not on the breath at all. - Redirect

When this happens, simply redirect your attention back to the breath.

The Reps

There’s nothing more to do—simply return back to the breath as many times as you need to.