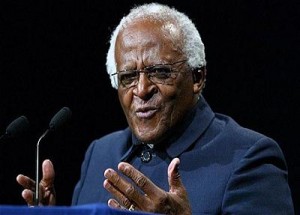

Dr. Frank Lipman: I’ve been introducing my readers to the concept of Ubuntu. Who else to better explain it than you! Bishop Tutu: Ubuntu is a concept that we have in our Bantu languages at home. Ubuntu is the essence of being a person. It means that we are people through other people. We can’t be fully human alone. We are made for interdependence, we are made for family. Indeed, my humanity is caught up in your humanity, and when your humanity is enhanced mine is enhanced as well. Likewise, when you are dehumanized, inexorably, I am dehumanized as well. As an individual, when you have Ubuntu, you embrace others. You are generous, compassionate. If the world had more Ubuntu, we would not have war. We would not have this huge gap between the rich and the poor. You are rich so that you can make up what is lacking for others. You are powerful so that you can help the weak, just as a mother or father helps their children. This is God’s dream.

Bishop Tutu: Ubuntu is a concept that we have in our Bantu languages at home. Ubuntu is the essence of being a person. It means that we are people through other people. We can’t be fully human alone. We are made for interdependence, we are made for family. Indeed, my humanity is caught up in your humanity, and when your humanity is enhanced mine is enhanced as well. Likewise, when you are dehumanized, inexorably, I am dehumanized as well. As an individual, when you have Ubuntu, you embrace others. You are generous, compassionate. If the world had more Ubuntu, we would not have war. We would not have this huge gap between the rich and the poor. You are rich so that you can make up what is lacking for others. You are powerful so that you can help the weak, just as a mother or father helps their children. This is God’s dream.

Dr. L: Having grown up in South Africa during apartheid and having seen the evils perpetrated, I’m constantly amazed at the lack of resentment, bitterness and the ability to forgive by the people who suffered so much under that brutal regime. Why do you think this is the case?

Bishop Tutu: There’s a deep yearning in African society for communal peace and harmony. It’s for us the summum bonum, the greatest good. For in it, we find the sustenance that enables us to be truly human, to have Ubuntu. Anything that erodes this central good is inimical to all, and nothing is more destructive than resentment and anger and revenge. In a way, therefore, to forgive is the best form of self-interest, because I’m also releasing myself from the bonds that hold me captive, and it’s important that I do all I can to restore relationship. Because without relationship, I am nothing, I will shrivel.

Reconciliation and forgiveness have deep roots in African political thought and spirituality. Anger, resentment and retribution are corrosive of this great good, the harmony that has got to exist between people. It’s reflected in the concept of Ubuntu. Remember, we’re talking about so-called ordinary people who’ve suffered grievously, who’ve committed themselves to this way because they believe deep down in their very being that this is the best course. But then, of course, we’ve also had the incredible example of a Nelson Mandela. He is an extraordinary icon of magnanimity, of forgiveness and reconciliation. Ultimately you discover, as Mandela did, that without forgiveness, there is no future. Forgiveness is not nebulous, impractical and idealistic. It’s thoroughly realistic. It’s real political in the long run. And that’s why our people have been committed to the reconciliation where we use restorative rather than retributive justice.

Dr. L: What do you mean by Restorative Justice?

Bishop Tutu: It’s a system of justice that focuses on repairing and building the relationship among perpetrators, victims and society. It draws upon traditional forms of justice practiced for centuries in Africa. We seek to do justice to the suffering without perpetuating the hatred aroused. It’s a kind of justice that says, “We’re looking to the healing of relationships, we’re seeking to open wounds, yes, but to open them so that we can cleanse them and prevent them from festering; we cleanse them and then pour oil on them, and then we can move into the glorious future that God is opening up for us.” To pursue the path of healing for our nation, we need to remember what we’ve endured. But we must not simply pass on the violence of that experience through the pursuit of punishment.

Instead–since we know memories will persist for a long time–we aim to acknowledge those memories. This is critical if we are to build a democracy of self-respecting citizens. As a victim of injustice and oppression, you lose your sense of worth as a person, and your dignity. Restorative justice is focused on restoring the personhood that is damaged or lost.

But restoring that sense of self means restoring memory, a recognition that what happened to you happened. You’re not crazy. Something seriously evil happened to you. And the nation believes you. That acknowledgment is crucial if healing is to go on and if the undercurrents of conflict are not to be left simmering, as they have been so many times in so many parts of the world.

Dr. L: The Truth and Reconciliation Commission obviously used Restorative Justice. This remarkable process gave perpetrators of human rights abuses on all sides of the South African conflict indemnity against prosecution, in return for a full declaration of the truth. It’s become a model for other countries trying to come to terms with legacies of political violence. How did you come to be Chairman of the Commission?

Bishop Tutu: In late 1995, I was looking forward to my retirement when Nelson Mandela (who was South Africa’s President at the time) appointed me chairperson of the Commission. And who can ever say no to Mr. Mandela? So my much-longed-for sabbatical went out the window, and for nearly three years we would be involved in the devastating, but also exhilarating, work of the commission.

Dr. L: What did you learn from the Truth and Reconciliation Commission?

Bishop Tutu: I’ve come to realize the extraordinary capacity for evil that all of us have, because we’ve now heard revelations of horrendous atrocities that people have committed. I’ve heard of the most awful things happening–things that were beyond my most pessimistic imagination. We’ve heard of an ordinary good neighbor–someone who was regarded highly in his community–whom in arresting someone, shot that person and burned his body. And not only burned his body, but also built a barbecue on the side of the road while doing it. The people who were perpetrators of the most gruesome things didn’t have horns, didn’t have tails. Any and every one of us could’ve perpetrated those atrocities. They were ordinary human beings like you and me. Devastating! But in the stories we’ve heard, I’ve been inspired that there’s also the other side, the side of magnanimity, of people who are ready to reach out to make change and to forgive.

It was more exhilarating than anything that I have ever experienced, and something I hadn’t expected. People who suffered untold misery, people who should’ve been riddled with bitterness, resentment and anger came to the Commission and exhibited an extraordinary nobility of spirit in their willingness to forgive. Take the Biehls, an American family whose daughter worked in South Africa on a Fulbright scholarship. She was murdered in the last days of apartheid. Her murderer appealed to be considered for amnesty by the commission. Her parents not only supported this, but have come to South Africa several times to do so, and have started a foundation to carry on her work here. Their openheartedness is an inspiration to many people who dream of a new South Africa. Human beings are fundamentally good. The aberration, in fact, is the evil one, for God created us ultimately for God, for goodness, for laughter, for joy, for compassion, for caring. So I have two lasting impressions: the horror of what we’re able to do to each other and the exhilaration at the nobility of the human spirit that so many victims demonstrate.

Dr. L: The Dalai Lama, Nelson Mandela, Martin Luther King, Mother Theresa and you too–all remarkable leaders–have endured tremendous suffering. Can you talk about the nature of suffering and how it creates inner strength?

Bishop Tutu: Suffering is part and parcel of the human condition, but suffering can either embitter or ennoble us. It can ennoble us and become a spirituality of transformation when we find meaning in it.

Suffering seems to also authenticate the leader, giving them a credibility that seems to come far more easily through suffering. So you see a Nelson Mandela, who was not President of a militarily or economically powerful country, and yet he stands head and shoulders above virtually every other states person in the world. Why? Well, it’s certainly his magnanimity, his readiness to have forgiven those who treated him so shabbily. I think we all want to see in the leader the attributes we wish we ourselves possess integrity, compassion, gentleness, magnanimity–the things that make you and me proud to be human. There are awful things about us, but we realize we’re actually made for the transcendent. We’re made for laughter, caring, sharing and goodness. And those leaders, who somehow embody these things, show us that it’s achievable. Yes, the sky is the limit, and we’re meant to reach for the stars and live God’s dream.

Dr. L: Why do you think that we have such deep admiration for these leaders?

Bishop Tutu: When we encounter a good person, we become reverent. Because we’re actually made for that goodness, and there’s an excitement when people see it embodied. But it’s actually achievable in a world where there’s so much disillusionment, and where people see so many eager to use their positions, to feather their nests. To have someone who’s genuinely altruistic makes you feel good. Ultimately, we recognize their goodness. Mother Teresa, she is good–not successful, not macho. The Dalai Lama is wonderfully mischievous, and yet he has an incredible well of serenity at the center of his life despite his being in exile for decades. And so to some extent, suffering has to be a component of what makes a good leader.

Dr. L: I feel so proud of what South Africa has accomplished since the end of apartheid. To me, it’s a model for the rest of the world. But there are still major problems. What can be done to address them?

Bishop Tutu: We’ve got to acknowledge and appreciate the wonder of what has happened. I don’t think that in South Africa we quite recognize how extraordinary it was. Everywhere I’ve been outside of this country, people can’t stop talking and marveling about what has happened here–the miracle of it. I say that if it could happen between an Afrikaner and an African here, given all that has happened, then there’s no reason why it can’t happen elsewhere; people see us as a sign of hope. But you can kiss reconciliation and forgiveness goodbye, unless the gap between the rich and the poor — the haves and the have-nots — is narrowed, and narrowed quickly and dramatically. So yes, we face very, very considerable problems. I used to be “Mister Disinvestment.” Now I would like to be Mister Investment and say, “Come! Come and be part of an exciting, exhilarating process. Come in! Come in on the ground floor and see a people do something that’s probably never happened before, people seeking to become something radically different from what their antecedents would’ve made us believe they were likely to become.”

Aside from poverty, the other issue is AIDS. But when you look at countries like Uganda, where there’s been a massive campaign, you see that it’s possible to turn the situation around.

Dr. L: Tell us about your new book, God Has a Dream: A Vision of Hope for Our Time (Doubleday, hardcover, Spring 2004, paperback, Spring 2005).

Bishop Tutu: So many of us feel despair because of all the suffering in our world and in our lives. We needed to be reminded about all the good that’s happening all this time, too; people caring for AIDS sufferers, pouring themselves out prodigally in compassionate service for others. And one needed to say that God hasn’t finished with God’s work. Creation is a work in progress. Evil isn’t going to have the last word. God uses us as collaborators, fellow-workers, and ultimately good and those who strive for it will prevail. I tried to present people with a way to look beyond the headlines, beyond the suffering to see God’s dream and how they might participate in realizing it.

God’s dream is that you, and I, and all of us will realize that we’re family; that we’re made for togetherness, for goodness, and for compassion. In God’s family, there are no outsiders, no enemies. Black and white, rich and poor, gay and straight, Jew and Arab, Muslim and Christian, Hindu and Buddhist all belong. When we start to live as brothers and sisters and to recognize our interdependence, we become fully human.

God’s love is too great to be confined to any one side of a conflict or to any one religion. People are shocked when I say that George Bush and Saddam Hussein are brothers, but God says, “All are my children.” It is shocking. It is radical. But it is true.

We tend to suffer from a sense of insecurity and inadequacy in our lives because our culture sets such a high store on success. People forget that God loves them as they are. God marvelously, miraculously cares about each and every one of us. The Bible has this incredible image of you, of me, of all of us, each one held as something precious, fragile in the palms of God’s hands. And God says to you, “I love you. You are precious in your fragility and your vulnerability. Your being is a gift.”

Love is universal. I mean, you don’t have to tell somebody that loving is better than hating. You don’t have to believe in God to know that stealing is bad. All of God’s children and their different faiths help us to realize the immensity of God. No faith contains the whole truth about God. And certainly Christians don’t have a corner on God. All of us belong to God. Even the nonbeliever is precious to God. And one simply tries to remind them that they’re made for transcendence. They are made for goodness. I hope readers, whatever their religion, will have new faith in themselves and realize just how beautiful they are, how precious they are and how much they truly matter.