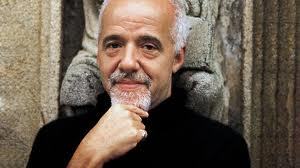

by Julie Bosman: A publishing industry that is being transformed by all things digital could learn some things from Paulo Coelho, the 64-year-old Brazilian novelist.  Years ago he upended conventional wisdom in the book business by pirating his own work, making it available online in countries where it was not easily found, using the argument that ideas should be disseminated free. More recently he has proved that authors can successfully build their audiences by reaching out to readers directly through social media. He ignites conversations about his work by discussing it with his fans while he is writing.

Years ago he upended conventional wisdom in the book business by pirating his own work, making it available online in countries where it was not easily found, using the argument that ideas should be disseminated free. More recently he has proved that authors can successfully build their audiences by reaching out to readers directly through social media. He ignites conversations about his work by discussing it with his fans while he is writing.

That philosophy has helped him sell tens of millions of books, most prominently “The Alchemist,” an allegorical novel that has been on the New York Times best-seller list for 194 weeks and is still a regular fixture in paperback on the front tables of bookstores.

This week Mr. Coelho releases his latest novel, “Aleph,” a book that tells the story of his own epiphany while on a pilgrimage through Asia in 2006 on the Trans-Siberian Railway. (Aleph is the first letter of the Hebrew alphabet, with many mystical meanings.) While Mr. Coelho spent four years gathering material for the book, he wrote it in only three weeks.

Spreading the word about the book should be easy; he has become a sort of Twitter mystic, writing messages in English and his native Portuguese and building a following of 2.4 million people. (A recent example: “When your legs are tired, walk with your heart.”) In 2010 Forbes named him the second-most-influential celebrity on Twitter, behind only Justin Bieber.

Mr. Coelho continues to give his work away free by linking to Web sites that have posted his books, asking only that if readers like the book, they buy a copy, “so we can tell to the industry that sharing contents is not life threatening to the book business,” as he wrote in one post.

From his home in Geneva, Mr. Coelho spoke about his new book, his feeling of connection to Jorge Luis Borges and his leisure time spent networking with his fans on Facebook and Twitter. Following are edited excerpts.

Q. The protagonist of your new novel, “Aleph,” sounds familiar: best-selling author, world traveler, spiritual seeker. How autobiographical is this book?

A. One hundred percent. These are my whole experiences, meaning everything that is real is real. I had to summarize much of it. But in fact I see the book as my journey myself, not as a fiction book but as a nonfiction book.

Q. The title of the book, “Aleph,” mirrors the name of a short story by Borges. Were you influenced by him?

A. He is my icon, the best writer in the world of my generation. But I wasn’t influenced by him, I was influenced by the idea of aleph, the concept. In the classic tradition of spiritual books Borges summarizes very, very well the idea of this point where everything becomes one thing only.

Q. When did you decide to become a writer?

A. It took me 40 years to write my first book. When I was a child, I was encouraged to go to school. I was not encouraged to follow the career of a writer because my parents thought that I was going to starve to death. They thought nobody can make a living from being a writer in Brazil. They were not wrong. But I still had this call, this urge to express myself in writing.

Q. Your most famous book, “The Alchemist,” has sold 65 million copies worldwide. Does its continuing success surprise you?

A. Of course. It’s difficult to explain why. I think you can have 10,000 explanations for failure, but no good explanation for success.

Q. You’ve also had success distributing your work free. You’re famous for posting pirated version of your books online, a very unorthodox move for an author.

A. I saw the first pirated edition of one of my books, so I said I’m going to post it online. There was a difficult moment in Russia; they didn’t have much paper. I put this first copy online and I sold, in the first year, 10,000 copies there. And in the second year it jumped to 100,000 copies. So I said, “It is working.” Then I started putting other books online, knowing that if people read a little bit and they like it, they are going to buy the book. My sales were growing and growing, and one day I was at a high-tech conference, and I made it public.

Q. Weren’t you afraid of making your publisher angry?

A. I was afraid, of course. But it was too late. When I returned to my place, the first phone call was from my publisher in the U.S. She said, “We have a problem.”

Q. You’re referring to Jane Friedman, who was then the very powerful chief executive of HarperCollins?

A. Yes, Jane. She’s tough. So I got this call from her, and I said, “Jane, what do you want me to do?” So she said, let’s do it officially, deliberately. Thanks to her my life in the U.S. changed.

Q. And now you’re a writer with one of the most prominent profiles online. Are you a Twitter addict?

A. Yes, I confess, in public. I tweet in the morning and the evening. To write 12 hours a day, there is a moment when you’re really tired. It’s my relaxing time.

Q. That seems to be the opposite approach of writers like Jonathan Franzen who blindfold themselves and write their books in isolation.

A. Back to the origins of writing, they used to see writers as wise men and women in an ivory tower, full of knowledge, and you cannot touch them. The ivory tower does not exist anymore. If the reader doesn’t like something they’ll tell you. He’s not or she’s not someone that is isolated.

Once I found this possibility to use Twitter and Facebook and my blog to connect to my readers, I’m going to use it, to connect to them and to share thoughts that I cannot use in the book. Today I have on Facebook six million people. I was checking the other day Madonna’s page, and she has less followers than I have. It’s unbelievable.

Q. You’re bigger than Madonna?

A. No, no, no. I’m not saying that.