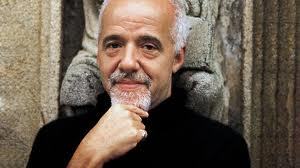

by Stuart Husband: Paulo Coelho believes if we all follow our dreams we can achieve love, money, success – anything we want.  It’s worked for him: he’s sold 100 million books, rubs shoulders with the stars and is worshipped by his fans. Stuart Husband discovers his secret

It’s worked for him: he’s sold 100 million books, rubs shoulders with the stars and is worshipped by his fans. Stuart Husband discovers his secret

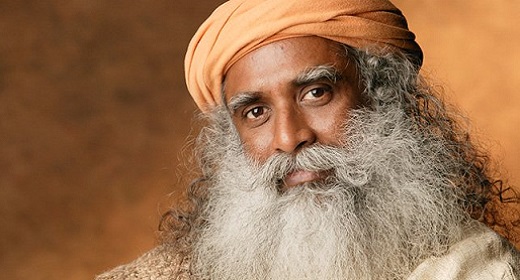

Walking down the street with Paulo Coelho is a disarming experience. People’s mouths fall open in a comic double-take as they spot him; many rush over to have their photographs taken with him; some merely clamp their hands to their mouths, shaken and overcome. Wherever Coelho goes, he tends, Pied Piper-like, to attract a train of attendants. Many call him ‘maestro’. Far from being irked by this, he seems to thrive on it. ‘Come on, come closer,’ he entreats, beckoning to a pair of middle-aged women and their camcorder. ‘Come get your pictures.’

‘You changed our lives,’ one of them manages to blurt, as Coelho wraps a thick arm round her waist.

He lavishes a beneficent smile on her. ‘It was a pleasure,’ he says with relish.

Coelho (pronounced Co-el-you) looks a little like a rock star, albeit, at 60, a slightly superannuated one. He has the terse physique of a farm labourer, and invariably dresses in black T-shirts and jeans: ‘There is less chance of them being destroyed in hotel laundries,’ he says, when pressed on the significance of his attire. His white hair is shaved short, and he’s dispensed with the short ponytail he once sported, though that hasn’t lessened his fans’ regard for him as a kind of Kahlil Gibran-like sage. Coelho is in fact one of the most successful authors in the world, with about 100 million books sold (‘Over 100 million,’ he clarifies, when I mention the figure; Coelho is definitely abreast of the numbers). One fifth of that figure has come from one title, The Alchemist, which Coelho wrote in two weeks, in 1987.

The Alchemist, like many of Coelho’s offerings, is less novel than fable. The original story can be found in A Thousand and one Nights and was later adapted by the Argentine author Jorge Luis Borges (Coelho, who is Brazilian, counts Borges among his favourite authors, alongside Henry Miller, William Blake and Oscar Wilde). It tells of a man (in Coelho’s version, an Andalusian shepherd boy; Coelho has said, many times, that he is that shepherd boy), who dreams that he must leave home to seek a treasure, only to find, on arriving at his destination, that the treasure is actually buried where his journey began. Coelho sends his shepherd to the Sahara desert, where an alchemist tells him, ‘Wherever your heart is, that is where you’ll find your treasure’. Sure enough, on returning home, he unearths a set of gold coins. The Alchemist, which has been translated into 64 languages, distils the message found in Coelho’s other eight novels, two memoirs, and various volumes of anecdotes and platitudes, including his online newsletter, Warrior of the Light: that if we pay attention to signs and portents, and follow our destiny, which Coelho calls our ‘personal legend’, then whatever is sought – love, money, inspiration, success – can be attained.

‘When you want something,’ he has written, ‘all the universe conspires in helping you to achieve it.’ This no-sweat combination of ‘Desiderata’ and the best-selling Christian self-help book The Purpose-Driven Life has won Coelho an army of eager adherents. Both delivery boys and princesses recognise his face. Even as the Monica Lewinsky scandal ran its sordid course, Bill Clinton was photographed carrying a copy of The Alchemist. Madonna has written, of the same book: ‘A beautiful work about magic, dreams, and the treasures we find on our own doorstep.’ Supermodels invariably sport a selection of the Coelho back catalogue in their totes. ‘It’s like music, really, the way that Paulo writes, it’s so beautiful,’ opined Julia Roberts, in a 2001 documentary about Coelho.

‘Can I picture 100 million books?’ ponders Coelho, in a warm, throaty rasp that’s enhanced by a prodigious cigarette habit. ‘I cannot. I remember going to the Maracana football stadium in Rio, which is the world’s biggest; it holds 100,000 people. This was after my sales had reached that number. I looked at all these people and that in itself, to me, was miraculous. Anything beyond that?’ He shakes his head. ‘It’s pure abstraction.’

He also demurs when asked to account for the success of his books. ‘I don’t know the reason,’ he says, shaking his head, ‘and if I find out, I’m going to lose the magic. I’m going to try to write to a formula. But I know that they have touched hearts, of course.’ His face breaks into a toothy gleam. ‘Last night, I was walking the street and I met an Englishman who said to me, I never saw a writer surrounded by so many people unless he has debts to be collected.’ He chuckles vigorously.

Many people have put Coelho’s success down to the benign, forgiving, pantheistic brand of spirituality enshrined in his writing. Open any of his books at random and you’ll almost certainly alight on one of its tenets – ‘all things are one,’ say, or ‘it is not a sin to be happy’. In Coelho’s cosmology, the quotidian – weather patterns, coincidence, the most mundane of events – is always miraculous, and his plots tend to be sweepingly allegorical, which may be why so many of his readers claim to see their own lives in them (this is literally true, in some cases: in The Zahir, a novel about a man who goes on a journey of self-discovery after his war-correspondent wife leaves him, the female character was based on the reporter Christina Lamb, who interviewed Coelho after returning from Iraq in 2003; perhaps this is one reason that Coelho says a daily prayer asking that, over the course of the next 24 hours, he will meet interesting people). Last winter, Starbucks printed a quote of Coelho’s on five million of its Venti cups: ‘Remember your dreams and fight for them. You must know what you want from life. There is just one thing that makes your dream become impossible: the fear of failure. Never forget your Personal Legend. Never forget your dreams…’

It therefore sounds a little disingenuous when Coelho announces that he doesn’t consider his books to be spiritual. This will come as news not only to most of his readers, but also to Waterstone’s (where his titles prop up the Spiritual Fiction section), and to his own characters that he cites in his defence, namely the Romanian prostitute in Eleven Minutes (who sanctifies those around her via the gift of transcendent sex), and the suicidal Slovene in a mental hospital in Veronika Decides to Die (who repents and sanctifies those around her via her new-found zest for life). But Coelho is adamant. ‘I don’t set out to write about spirituality, I am free to do something different every time. Right now, I am just finishing a novel set in the world of fashion, about why we are so fascinated to spend so much money on dresses, suits, even knickers. Like all my books, I am looking at something in an effort to understand it better.’ He shrugs. ‘When you say spirituality, maybe it’s because I try to see something from a different perspective.’

The talk of spirituality is given added piquancy, given our surroundings: we’re sitting in a sepulchral meeting-room in the luxurious Parador – a former monastery, now a five-star hotel – in the northern Spanish city of Santiago de Compostela, whose huge cathedral, on the Unesco-protected square, is the culmination of the 560-mile Christian pilgrimage from Saint-Jean-Pied-de-Port in France, made since medieval times to the remains of St James, allegedly buried in the cathedral’s vaults. Coelho undertook the walk himself in 1986, and subsequently wrote about it in his first book, The Pilgrimage (original title: Diary of a Magus). ‘It was the turning point of my life,’ he says emphatically. ‘I had this dream to become a writer since I was a teenager. I was nearly 40 at the time, a late starter, and I felt OK, it’s now or never.’

Coelho was born in Rio in August 1947; ‘I am 100 per cent Virgo,’ he says, ‘stubborn, over-organised, slightly abstracted from the rest of the world.’ His father was an engineer, and expected his son to follow in his footsteps. His mother was a devout Catholic, and sent her son to a Jesuit school. They took a dim view of his desire to write, and an even dimmer one when he took to declaiming his poetry on the beaches amid Rio’s proto-Beats. They sent him to a mental institution where he received electroshock therapy. In the late 1960s, he became a fully-fledged member of the Brazilian underground, growing hippy hair, doing drugs, and devouring the writings of the occultist Aleister Crowley. He met a singer called Raul Seixas and began writing lyrics for him. Seixas became a huge star, and one of his and Coelho’s biggest hits was called Sociedade Alternativa; soon, kids all over Brazil were singing its catchy refrain – ‘Do what you want/Because it’s the whole of the law/Long live the Alternative Society/The number 666 is Aleister Crowley.’

‘I’ve presided over a few black masses in my time, sure,’ grins Coelho. ‘I wouldn’t recommend it necessarily, but every young person should allow the flame of rebellion to manifest in some way, because if you don’t see the other side of the coin, you are just a sheep. You’ll have some risky experiences, but everyone knows his or her limits, I believe.’ (This train of thought naturally brings him to Amy Winehouse: ‘I love her,’ he declares. ‘She doesn’t seem like the happiest person on earth, and I guess she will either die or she will survive, but I believe it will be the latter; she has a talent to nurture.’)

In 1974, Brazil’s military dictatorship decided that Coelho’s work was subversive and arrested him; he was then kidnapped by paramilitaries, who held him for a week, accused him of being a guerilla fighter, and tortured him by applying electric shocks to his genitals. He gave up religion for several years after that, writing television bio-pics and soap operas, returning to the Catholic fold after marrying his fourth wife, Christina (Coelho, deeply superstitious, refuses to countenance the use of the word ‘last’, except in reference to her). He then vowed to undertake the pilgrimage after meeting a man whom he refers to in his writing as ‘my Master’, who inducts him into something called the Order of Ram (Regnus Agnus Mundi, or Rigour, Adoration, Mercy), a Catholic sect for the study of symbols – think a hippy version of Opus Dei (though efforts to verify its existence outside of Coelho’s oeuvre have proved frustratingly futile).

The Pilgrimage is concerned mainly with Coelho’s efforts to locate a sword left by his Master somewhere on the road to Santiago; a Lord of the Rings-esque quest underlined by the appearance of a guide called Petrus who teaches Coelho various yogic-style Ram exercises. Along the way Coelho wrestles with his personal devil, who turns out to be a black dog named Legion, achieves a state of agape – or ‘the love that consumes’ – and foresees his own death. Quite how literally we’re supposed to take all this is a moot point (though it’s reported that several pilgrims now take a substantial detour in order not to pass by the spot where the fearsome Legion first attacks), and one that the Santiago city authorities are happy to overlook in favour of the fact that the number of pilgrims has increased tenfold since his book came out.

The previous night, Coelho was honoured by having a street named after him in the city; there’s also a Paulo Coelho Suite at the Hotel Ambasciatori in Rome, and a Paulo Coelho hot chocolate drink at the Bristol hotel in Paris. ‘Do I get royalties?’ he smiles. ‘No, I get none, but I need none. Writing The Pilgrimage enabled me to fulfil my own personal destiny.’ He shows me a crude tattoo of a butterfly on his left forearm. ‘This is a symbol of alchemy and transformation,’ he announces. ‘It’s a painful process, but you can be resurrected as a totally different entity, though with the same essence.’

I ask if he now finds writing easy. ‘Well, it’s not difficult for me to put my feelings into written form. I try to be concise and to go direct to the subject. This is what people like about my work, and what the critics hate. They want more complicated books.’ (Indeed, Brazilian critics say that translation from the original Portuguese must improve Coelho’s prose; a Sao Paulo newspaper columnist’s comment that Coelho writes in a ‘non-literary style’ is one of the more magnanimous verdicts).

Coelho’s name is about to be lent to another product; a fountain pen from the venerable Italian manufacturer Montegrappa in a limited edition of 1947, commemorating his birthdate (1,000 of them in silver, 900 in silver and emeralds and 47 in yellow gold, emeralds and diamonds; the latter will retail at around £10,000). The nib is adorned with a butterfly and the shaft with a relief map of the Pilgrim’s Route to Santiago. It’s not the first time that Coelho has been associated with a luxury brand; last year, the International Watch Company commissioned him to write seven short stories, one about each model the company produces (his fee went to benefit the Paulo Coelho Insititute, a foundation that helps children who live in the Rio favelas). Coelho’s brand awareness and new-found interest in fashion may have been fomented by his personal assistant Alessandro, a dapper, Hermès-belted German, half Coelho’s age, who confides that he also works in brand consultancy for the likes of Hugo Boss and Formula 1; and, while he may be in awe of Coelho (‘Did you know that Nelly Furtado only decided to have a child after reading one of his books?’ he asks me, wide-eyed), seems to regard him as another trademark to be turned to account. Coelho himself, while waxing lyrical over the pen, seems to be genuinely unconcerned with Mammon.

While his books have brought him great wealth – he has an apartment in Paris’ sixth arrondissement containing an improvised archery course, as well as a converted mill in the French Pyrenees and an apartment on Copacabana beach – he’s artlessly open and approachable; and, as his almost daily blogging attests, he prides himself on his close relationship with his readers (one that is more than reciprocated – ‘You have been like the mother bird that helps her little ones fly,’ runs a typical response to a recent post). ‘I am an internet junkie,’ he declares with glee. ‘I have a public inbox which receives over 1,000 emails a day and which I employ four people to answer, plus my forums, my blog, and an inbox just for work. This is what I do. I don’t socialise or go for cocktails and dinners. I hate to be smart. People know they can always reach me.’ But doesn’t he leave himself a little too open to people who think he can heal the world, or at least their world? ‘Not really. I actually ask them a lot of the questions. I expect them to have some answers.’ What about the Irish woman who marched onto his terrace and announced that a satellite had told her she should come and commit suicide in front of him? ‘Oh, unscheduled visits happen sometimes,’ he says, dismissively. ‘I’d say one in every 100 readers may have this kind of extreme reaction. But you know, I sent her off on the road to Santiago and she eventually called to say she’d changed her mind about killing herself.’ He shrugs. ‘I’m not going to wall myself off. But I have put in a gate.’

Coelho’s literary superstar status is unlikely to recede soon, particularly with the release next year of a film version of Veronika Decides to Die, starring Sarah Michelle Gellar and David Thewlis (the much-mooted big-screen adaptation of The Alchemist is apparently mired in development hell). Coelho will doubtless react to future vicissitudes with his customary – indeed, almost preternatural – equanimity. ‘I look for the mystery in everything,’ he says happily. ‘I don’t try to control my days. The problem for most people is that they think every single day is the same. Or they are held back by fear. Fear of death, fear of whatever. Now, death holds no dread for me. I foresaw my own burial, and I broke free and flew away. I know we’ll carry on. There is an afterlife. I am convinced of this.’

He claps his hands. ‘Now, a cigarette. That will surely kill me eventually, no?’ He jumps up, and we walk down the hotel corridor, Coelho adopting the thumbs-hooked-out-of-jeans-pockets stance favoured by Jeremy Clarkson and his ilk. Out on the square, many pilgrims, awestruck equally at the sight of Coelho and the cathedral, gawp from one to the other. I ask him to sign my copy of The Alchemist. Not for Coelho the likes of ‘Best regards’ or ‘Good wishes’. He takes his pen, and, with a rolling flourish, writes ‘Follow your dreams’.