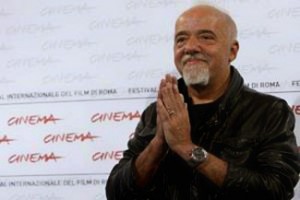

by Alan Riding: ST. MARTIN, France, Aug. 23 – Letting out a cry of delight, Paulo Coelho called a visitor over to read a new e-mail message announcing that French sales of his latest novel had exceeded 320,000 since its publication here in May.

Alan Riding/The New York Times 8/30/05

Alan Riding/The New York Times 8/30/05

“That makes my day,” he said. “I had hoped they would go over 300,000.”

Well, why not? Every writer wants his books to sell well.

Yet, somehow, Mr. Coelho (pronounced co-AIL-you) is different from most.

Now 58, the Brazilian author has over the past 18 years sold more than 65 million copies of his books in 59 languages, ranking him as one of the world’s most successful popular writers. Each new book, which he writes in Portuguese, involves an extraordinary operation of translation, printing, distribution and marketing. And then, it seems, Mr. Coelho sits back and counts the sales.

The key that unlocked this writer’s dream world was “The Alchemist,” his inspirational fable about a Spanish shepherd boy who travels to the pyramids of Egypt in search of a treasure and instead finds his “personal legend,” or destiny. Mr. Coelho said that book alone, first published in Brazil in 1988, had so far sold close to 27 million copies worldwide, including 2.2 million in the United States.

Now, however, Mr. Coelho’s attention is on his new semi-autobiographical novel, “The Zahir,” which has already topped the best-seller list in a score of countries and will be published in the United States in September by HarperCollins. So far, “The Alchemist” (HarperSanFrancisco, 1993) has been his only American best-seller, and Mr. Coelho is looking to “The Zahir” to raise his profile afresh in the United States.

“I am not in the United States what I am in France or Spain or Germany,” he said in a long conversation in the all-glass dining room that reaches into the garden of his comfortable but simple home in the Pyrenees Mountains. “I have never broken the barrier of the press. In the United States, I am a great success, but I am not a celebrity.”

Still, for all his fame elsewhere, Mr. Coelho, a slimly built man with a goatee, does not live the life of a celebrity. He spends half the year in Rio de Janeiro, the city of his birth, but it is in this tiny village where he says he feels most at ease. When not writing, he cuts the grass, practices archery, reads and keeps in touch with the world electronically.

“I have 500 television channels and I live in a village with no bakery,” he said with a laugh.

What brought him here, though, was not the bucolic appeal of rural France. Rather, it was that St. Martin is just 10 miles from the shrine to the Virgin Mary at Lourdes.

“I am a Catholic,” he said, “not so committed to the church, but to the idea of the Virgin, the female face of God. I have spent every New Year’s Eve since 1992 in Lourdes. I spend the hour of my birth every year in the grotto. It’s a place with meaning for me.”

Not that Mr. Coelho is a Roman Catholic writer. Indeed, through their portrayals of more generic spiritual searches or inner journeys, many of his books have spoken to readers in countries with cultures and beliefs as different as Egypt and Israel, India and Japan. His explanation?

“I know we have the same questions,” he said. “But we don’t have the same answers.”

Mr. Coelho’s own journey has not been without incident. His rebellious adolescence led his parents to send him to a psychiatric hospital on three occasions. In the early 1970’s, living the life of a hippie and devoted, in his words, to “sex, drugs and rock ‘n’ roll,” he wrote lyrics for protest songs that prompted the military government that controlled Brazil then to jail him three times. Later, he worked in the record business – until he was fired.

Then, at 36, he decided to follow the medieval pilgrims’ road to Santiago de Compostela in northwestern Spain. That resulted in his first book, “The Pilgrimage,” which, while barely noticed at the time in Brazil, persuaded him not only to dedicate himself to writing but also to pursue his search for some meaning to his life. His second book, “The Alchemist,” also sold slowly until it became an unexpected best seller in France in the early 1990’s – and then the world followed.

Even now, though, Mr. Coelho says his search goes on.

“Each book is a little bit more about me,” he explained. “What surprises me is when I’m called a spiritual writer. For me, the pursuit of happiness is a lie, as if there were a point when everything changes, when you become wise. I believe enlightenment or revelation comes in daily life. I look for joy, the peace of action. You need action. I’d have stopped writing years ago if it were for the money.”

In “The Zahir,” he said, he wrote about a writer because that is what he knows about. As it happens, this writer, who tells his story in the first person, is also immensely successful, his books global best sellers that, like Mr. Coelho’s own books, are occasionally savaged by literary critics but are lapped up by loyal readers. The story, though, is not Mr. Coelho’s story.

In the narrative, the writer’s journalist wife, Esther, decides to become a war correspondent, then disappears mysteriously. Eventually, he meets a mystical young man from Kazakhstan called Mikhail who seems to know Esther’s whereabouts but insists that the writer must know himself better if he can hope to be reunited with her. And after a series of adventures and omens, the writer duly heads for Kazakhstan.

“The Zahir,” an Arab concept borrowed from a short story by Jorge Luis Borges, is described by Mr. Coelho as a thought or idea that gradually becomes obsessional. In the book, the narrator’s “Zahir” is the missing Esther.

“There’s a lot of me in it,” Mr. Coelho said, albeit noting that he has now been married to his artist wife, Christina Oiticica, for 26 years. “But the character is more egotistical. I’m also egotistical, but not the way the character is. This guy is successful, he has everything, but his wife has left him. The most important value – love – is missing. What is wrong with this institution called ‘marriage’? What is wrong with this institution called ‘the pursuit of happiness’?”

As so often with Mr. Coelho’s books, including other major best sellers like “Veronika Decides to Die” and “Eleven Minutes,” the reviews for “The Zahir” have ranged from admiring to insulting, with the most scathing language proffered by those who believe Mr. Coelho poses as a guru.

“I never say I am a guru,” he insisted. “That person does not exist. Readers only want to know if I have the same question as they have. But if I gave an answer, they’d soon see it was false. Many readers send me e-mails saying their lives have changed. But I didn’t change those people. Everything was ready. Perhaps the book changed them.”

As for negative reviews, he says he is stoical.

“No one is going to change the way I write,” he said. “Borges said there are only four stories to tell: a love story between two people, a love story between three people, the struggle for power and the voyage. All of us writers rewrite these same stories ad infinitum.”

“But the one thing I cannot stand,” Mr. Coelho went on, “is criticism of the reader, that the reader is dumb. You can speak badly of me, of my books, but you cannot speak badly of the reader. It’s like saying, ‘Everyone is dumb; the only one who isn’t is the critic.’ That’s not fair.”