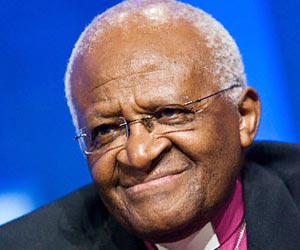

by David Hamburg: In the prevention of mass violence no one in the world has done more than Desmond Tutu.  Why wasn’t there a genocide in South Africa? I personally believe that one of the main reasons was the presence, the behavior, the stature of Desmond Tutu.

Why wasn’t there a genocide in South Africa? I personally believe that one of the main reasons was the presence, the behavior, the stature of Desmond Tutu.

One factor was a deep commitment on the part of key leaders–notably Desmond Tutu and of course Mandela–to working toward an inclusive democratic society through non-violent means at a time where there was every provocation for violence, for revenge.

Desmond, in those days you were the principal spokesman. Mandela was in prison and you were out in the world, explaining the nature of the oppression; and yet I cannot recall a single occasion where there was a tinge of hatred or violence. It was factual, to get us to understand what was happening and why it was so important to bring about changes, and always oriented towards a constructive outcome in the sense of inclusive democracy.

The Nobel award in 1984 gave you a bigger platform for teaching all of us not only about what was happening in South Africa, but a fundamental moral code that could help the world deal with South Africa and other similar problems.

Tutu: Credit must be given to many other people. I became the leader of our struggle by default because our real leaders were either in jail or in exile or restricted by house arrest or pending orders. I came into this sharing the policies of the African National Congress, having been influenced greatly by Gandhi’s Satyagraha. So I wasn’t a pioneer, I was continuing a tradition.

The ANC had boycotts, the traditional way to bring your plight to the attention of the authorities, and the passive resistance movement in the 1950’s; and delegations to petition the powers that be. So I wasn’t innovating. I came into this tradition, especially when I became dean of Johannesburg. The media in South Africa for a very long time were favorably disposed and gave me the opportunity of putting across the plight of our people and the fact that we were committed to working through non-violent means.

That’s one thing; the second, David, is a crucial part of our struggle. We would not have made it without our friends. Being friends with such important people as you made me Halal/Kosher for people who might have wondered, is he not a little bit off his rocker? You and people like yourself vouched for me. You people assisted me in making the crucial strategic connections; and you, in your self-effacing, gentle way, were a very important part of our strategy. I want to stress that we were very fortunate in the allies that we had abroad, especially in the United States.

Even when we were vilified at home you could say, we know that we have the support of the black community and the oppressed; we are giving voice to their plight. That was important for the question of credibility because the Apartheid government would make out that we did not have a constituency. I didn’t look for a constituency; but it was important that the black community supported us; and we also were supported by young people. Students at university and college campuses were fantastic in support of us.

I knew too that I could count on the prayers of so many around the world. That was very important because there are times where somebody would ask you a very tricky question and I was surprised sometimes at the answers I was able to give. Later on you think “I couldn’t have said that, could I?” and I am quite certain that some dear old lady somewhere or a nun in a way-out convent was at that moment saying a special prayer for us. So we could appeal to our people to hold their horses. And once Nelson Mandela was released you had people who were held in very high regard. Chris Hani had made a name for himself in the armed wing of the ANC, so you couldn’t accuse him of being a coward when he was prepared to say to the young Turks that we should reckon now on laying down arms and give negotiation a chance. And Joe Slovo–again people could not accuse him of being a coward; he’d been very prominent in the overseas armed wing, so Joe Slovo–and Chris Hani before he was assassinated–were able to sell the so-called sunset clause, wherein the negotiation said let’s not be too rough on these apartheid guys–things like they won’t lose their pensions. Those were sweeteners that helped to lubricate the negotiation.

Hamburg: It’s quite often said that many countries are capable of generating democratic leadership. The question is how South Africa generated what we call “depth on the bench”–not only Desmond Tutu and Nelson Mandela, but a considerable number. Are there lessons for the world about how you encourage incipient democratic reformers to real effectiveness in changing their own countries?

Tutu: You set up nurseries. One of our nurseries was a so-called mass democratic movement, the United Democratic Front, which was really the brain child of Alan Boesak. I think at the time of a struggle we really were idealistic. There was an incredible degree of altruism. It was a very important characteristic of the time and this is why now we are complaining that people are not being taken into the confidence of our leaders.

In the time of struggle they had street committees, all kinds of structures where people spent a lot of time arguing about which way we should be going; and once a decision was arrived at it was a decision that everybody could own. It wasn’t something that had been thrust on them. The leadership of these community structures had things very familiar in their hands and were very good about saying we have a particular code of conduct and there are things that are not acceptable. There is conduct that is not acceptable as you might have seen in the Winnie Mandela saga ,where Winnie had given marvelous, courageous leadership for a very long time. One has to pay tribute to her for that. But the pressures began to tell. We can criticize her but one has to say she withstood very considerable pressures. The Apartheid system threw everything at her to try to break her spirit and something did go wrong somewhere. She got involved in very questionable enterprises and eventually the leadership of the mass democratic movement had to stand up and be counted and I think it was one of the most difficult things they had to do to discipline her and they did say they were distancing themselves from what she did, which meant that there was in fact a code of conduct.

On the whole people seemed to abide by it.

Hamburg: That’s a fundamental point. There was a code of conduct forged first by a relatively small group of deeply committed and gifted people that grew into a mass democratic movement which shared and further refined the code of conduct and made it a way of life to which one was committed. That helped to bring along young leaders, so that you got democratic leaders in almost every community.

Another thing you touched on [was] international help. In learning lessons from the experiences of pioneers in preventing mass violence, we have to think about the role of the international community. It’s often said that the international community can’t really do much. A tyrant is free to do whatever he wants behind the wall of sovereignty. That was said about trying to help South Africa. Now you built a constituency, partly with your gifts, your personality, and your deep moral commitment. You clarified the moral basis for opposition; you also clarified economic and political and pragmatic considerations on how South Africa, how all of Africa would be better off if there were a transition to a democratic South Africa.

So the cognitive content as well as the moral content of your leadership –along with others’ of course–helped to build a broad constituency in the United States and other major democracies. It wasn’t easy. Cy Vance and I convened informally a group of leaders from a number of the major democracies and tried to get a small bit of policy coordination. It was very difficult. Outsiders can’t really change the nature of the regime.

You mentioned the young people. At the time Alan Boesak was arrested I convened a group of university and foundation presidents, and one of our thrusts was to activate college student movements. The presidents went back home and did everything they could do, and that in turn helped legitimize well known universities and we had a small non-violent army of young people. Then opportunities were provided for those young people to discuss with their faculty and their administrations and even with their trustees, some of whom were bankers. Nowadays in retrospect everyone says the financial sanctions were a crucially important thing.

Tutu: Absolutely, but it was a number of things. It was quite important the sports boycott was also in place, because South Africans are sports mad–rugby and cricket especially. And when they couldn’t play their traditional rivals, especially New Zealand and Australia, that hit them in a way that we sometimes underestimate. I think it was far more effective than even economic sanctions. They got to understand that the world regarded them as pariahs and they were quite unable to understand how old Commonwealth friends like Australia, New Zealand, and of course England could turn their backs on them.

There was this build up of the world’s total abhorrence of the system. There were some good people involved– Father Trevor Huddleston, for example, who was the president of the international anti-apartheid movement. He really had the gift; he could touch people. He said, to mark Nelson Mandela’s 70th birthday there was going to be a gathering at Hyde Park Corner, and he asked young people–most of whom had not been born when Nelson Mandela went to jail—to come, as in a pilgrimage, from different parts of England. A quarter of a million converged upon Hyde Park Corner. Trevor said, “Let this be Nelson Mandela’s last birthday in prison.” That was 1988. In 1990 he was out–the young people at university campuses were incredible.

I went to Downing Street and had a nice 50 minute meeting with Mrs. Thatcher, and spoke for 20 of those minutes. She was very charming, but as I tried my pitch on economic sanctions she wouldn’t buy that. And of course I tried meeting with President Reagan. He’d been totally dismissive until the Nobel Prize happened and I got a call from the White House. I was in New York at the time and met with him, but he also was adamant and had his constructive engagement policy. These two very important leaders of the Western world were very firmly against sanctions, but we appealed over their heads; and it wasn’t the young people exclusively, but I think they were a very very important element. They came about that time when they ought to be worried about their grades–exam time. I remember going to Berkeley and the students were sitting out in the quad demonstrating to urge the institution to diversify; and they did effect a change in the moral climate.

Hamburg: And this had feedback to South Africa, so there was a sense in South Africa that there’s a lot of support in the world. Furthermore, for the government there was a sense of becoming a pariah.

Now what about international organizations? You mentioned the Commonwealth, and, of course, the UN. Cy Vance was very well received in all sectors in South Africa; he was a UN representative, not a US representative, a special representative of the Secretary-General. He made clear to everybody what he thought about the system and what he thought about the promise of democratic change. But whether it be the UN or the Commonwealth, what do you see as the role of international organizations, and what might be done today better? For example, you and I served together on the Secretary-General’s committee to prevent genocide. There’s more awareness and organization within the UN and some other international organizations about these atrocities, genocide or otherwise. What do you see about the role of international organizations, then and in the future?

Tutu: Then you found most of the western countries you were expecting to push for democratization at a time where [they were] least inclined. They were engaged in the Cold War and it was not easy to change mode, to get to the point where you thought the Soviets might now become allies.

So one hoped that because the Cold War had ended the UN would take a more prominent role; but the UN is only as effective as its member states want to make it. Nowadays they have greater opportunities, especially now that they have responsibility to protect, which overrides the sovereignty of states.

I am disappointed that the UN can so easily get [intimidated? incapacitated? derailed?](_) We saw it over Iraq, and more recently with Burma and Zimbabwe. You would have thought they would appeal to the doctrine of responsibility to protect, and I am ashamed to say that my own country was a major stumbling block, because I think that a number of the big powers were keen at least to send an envoy to Zimbabwe just to make Mugabe aware that the world is looking so he wouldn’t unleash his militia, as seems to be happening, on supporters of the MDC.

A great deal of credit is due to you that the UN set up this special committee for prevention of genocide and made it a fairly high profile unit. It is largely due to your persuasive eloquence that both Kofi and his successor have seen that this is an important thing.

Now when you think of Burma or the Sudan, China has considerable leverage. They were able to get Sudan to agree to an enlargement of the UN force and also to some extent get Burma to be slightly less brutal. Countries like India, Thailand, China could do a great deal to bring about significant improvement in Burma, and in Zimbabwe. I believe that South Africa is holding back others to some extent in Zimbabwe.

Hamburg: Our efforts at the UN never would have been possible had you not been a member of the committee that I chaired. We would not have gotten this unit for Prevention of Genocide and now extended it to the possibility of protection. Maybe, in light of what you were just saying about the current bad situations, we really ought to focus on what can the UN do to shape up member states who have the capacity to make a beneficial difference and are not acting. Of course, Kofi Annan showed great courage in addressing them and got hit hard for doing so.

There’s also the question, how could the UN help regional organizations become more effective? Regular meetings of the Secretary-General with leaders of the regional organizations–that’s happening now, and I think it’s going to continue. That’s a start, but we should probably discuss in our committee how the UN can do more to mobilize both member states with the capacity to contribute and also regional organizations. The international community has a long way to go in this respect, just because member states can block it both in the General Assembly and in the Security Council. Of course, your voice is very important in that kind of situation, as an individual or as a member of this committee.

Now I want to come to the great day when Mandela made the long walk from prison and we began work on how to put democracy together. The international community, private and public, was very helpful in South Africa’s first democratic election and in drafting that excellent constitution, which is now a model for the whole world. Then came the Truth and Reconciliation Commission, which became fundamental because of suspicion and hostility on both sides, and many doubts–about whether democracy would work, whether there would be revenge, since the majority had been oppressed so badly for so long. And you came along with the Truth and Reconciliation Commission, which is now in one form or another spreading through the world.

I serve on the board of the International Center for Transitional Justice, which grew out of your commission. It advises people in different parts of the world how, in the context of their own history and culture, they can adapt what you did. But I think the world needs to understand better what you did, how you saw that commission. Looking back on it now, describe for us the essence of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission.

Tutu: First of all, it’s important that you should know I had nothing to do with the genesis of the commission. Alex Boraine, who became the deputy chair of the commission, played a significant role in the build-up to the commission. He had a party called Justice in Transition, which was working on the modalities. And then the ANC itself–probably the only liberation movement that ever did this–had appointed commissions even before they came to power to investigate atrocities committed by their own members in camps in the countries where they had been given asylum. So it was very largely the ANC’s baby. And Kader Asmal, in his inaugural lecture as professor of human rights law at the University of Western Cape, mooted the idea of a Truth and Reconciliation Commission. We were lucky to have had Ed Helm–and Nelson Mandela, because he would have been able to sell almost anything to his constituency. It was not universally popular; there were a lot saying, no, we want a Nuremberg type of solution. He, with his magnanimity, was able to appeal to people and say, “Look, we have a choice. We can go the path of retribution and revenge or we can go the path which I recommend, the path of forgiveness and reconciliation.”

A lot of the former Apartheid government people wanted blanket amnesty, and fortunately the people who negotiated our constitution rejected that option. The Nuremberg option was not a real option because Nuremberg, as you know, happened after the allies defeated the Nazis. We had a military deadlock–neither side had won an outright victory over the other. So it was understood that you really look for a compromise and you had to accept that. They said that for political offenses, if someone had been guilty within the stipulated period, 1960-1994, and they were able to make a clean and full disclosure, then amnesty would be granted.

For the victims they said, we are going to try and rehabilitate the dignity of victims: one, by enabling them to tell their story; and two, by their being eligible for reparation. Not compensation–there is no way you would ever compensate people for losing a husband or a son. On the other side, they would then lose the right to take the matter to court to claim damages. We speak about Nelson’s magnanimity. We ought in the same breath to acknowledge the generosity of spirit of those who were the victims. It was an extraordinary experience when you met people who should have been consumed by bitterness and hatred. They were amazing. I had not known that just telling a story–well, you would know as a psychiatrist–that just telling a story could be so therapeutic. We had a young man who was blinded by police action tell his story. When he finished, one of the panel asked him “How do you feel now?” A smile broke out on his face and he said, “You have given me back my eyes.” So we had those generosities.

There were very serious weaknesses. One was that they thought we ought to hit the ground running, with nothing; and I don’t think anyone would wish that even upon their worst enemy. One of the big weaknesses was that amnesty would be of immediate effect. If someone satisfied all the conditions laid down in the law they would get amnesty straight away. With the victims the process was tortuous. Once we said so and so qualifies for reparations all we could do was make a recommendation to the president, and then the president would take this to parliament and parliament would approve. We were incredibly ungenerous to people who had been so remarkably generous. It took forever for reparations to be given and when they were given they were piffling amounts.

We had made a recommendation that people should be given a grant ranging from about 17,000 rand a year to 26,000 rand, which is about $3,000-$4,000 dollars maximum. And we said that this should be over 6 years, which we could have afforded. And having taken all those years, some of the people who had come before the commission had died. That was a very serious weakness on the part of our commission.

The second was that whilst we were able to have got–especially from the police–very many people, the military as well, a lot of the big fish got away. We encountered a lot of hostility frrom the white community and I lay the blame squarely on the shoulders of the leadership of the white community. They were generally dismissive of the commission; and the Afrikaans newspapers especially were vilifying and poking fun of the commission. So we had very few come to take advantage of this generous offer. We are sad for ourselves; but because this is a moral universe they are still having to live with themselves. They have to wake up every morning and remember whatever atrocity they committed–and yet they had the opportunity that could have removed this albatross from their shoulders.

Hamburg: I want to ask you one more question. There’s a movement to denuclearize the world, which sounds as fantastic as it seemed some time back to get democracy in apartheid South Africa. A group of us is starting this in a more serious way than has ever been done. It’s going to be worldwide very soon, and with analytical work on both the technical and political obstacles, what stands in the way? But there are all kinds of reasons why countries hang on to weapons or build weapons, and that’s tending to spread now: the big powers have substantially improved their status. Their attitudes and behavior have become worse in recent years, so it will take an awful amount of doing. One of the factors is, why doesn’t anybody ever get rid of nuclear weapons? South Africa did and there seems to be very little illumination about why that happened. Can you cast any light about why that happened?

Tutu: No, but I thought you had been instrumental in persuading Gorbachev. What did you do? I thought that you hit the nail on the head in your book–the crucial role of leadership. We could have taken a wrong turning in South Africa if the leadership had been different–if somebody said you show that you are in charge by being macho and what he decided lost and we moved in a different direction. It has got to be something that’s done on both sides or done by all. But I can’t imagine the impact if, for instance, your country were to say, even unilaterally–I mean, are we dreaming; but can you envisage an occupant of the White House who said, apart from being obscene, this is wasteful, and it leaves all of us on the brink.

Hamburg: So your emphasis is clearly on mobilizing leadership in any way we can across the various nuclear divides. Well, I deeply regret that time has run out and I can’t thank you enough for this extraordinary interview.