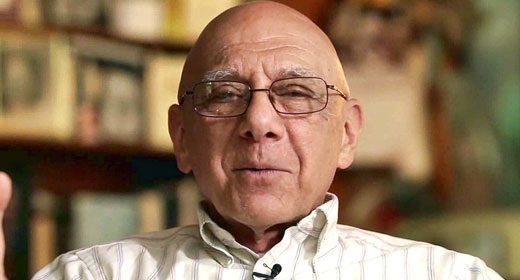

by Rabbi Levi Welton: Passionate about teaching the Holocaust, Ernie Hollander debated a denier on TV. Then the impossible happened…

The Satmar Rebbe once said “Anyone who has numbers on their arm has the power to give blessings.”

My father raised me to take this seriously and would always tell me to request a blessing from Holocaust survivors, whom he referred to as “Kedoshim”, aka “The holy ones.”

When I was eleven years old, my fatherRabbi BenZion Welton would gently wake me up at 6 AM to bring me to shul. It was still dark outside. As we drove over to Beth Jacob in Oakland, California, I’d nap in the car. Then we’d walk down the thin hallway to the small “morning services” chapel tucked into a forgotten corner behind the magnificent main sanctuary.

I walked in the shadow of my father towards the door. I remember hearing the muffled sounds of prayer as my nostrils widened to take in the scent of freshly brewed coffee and deliciously old books. I sat on the pew in between the two great luminaries of my childhood, my father and Chabad RabbiYehuda Ferris.

The chapel could barely house the two dozen people that gathered there every morning to pray. There was only one person whom my father would never let me leave without shaking his hand. This was Holocaust survivor Ernie Hollander, of blessed memory.

Although I didn’t know it at the time, Ernie had come from a long line of rabbis that dated all the way back to his family’s persecution in the Spanish Inquisition. His great grandfather was HaRav Shlomo (ben Yosef) Ganzfried, author of the Kitzur Shulchan Aruch. Ernie’s father was also a rabbi who owned a flour mill in Czechoslovakia. Ernie and his seven siblings lived happily with their father and mother until the Nazis invaded and murdered his father before his very eyes. Ernie and the rest of the children were sent to Auschwitz. He never saw his mother again.

When the war ended, Ernie, his baby brother Alex and one surviving sister tried to trach down the rest of their family but they had all been murdered during the war. Ernie heard a rumor that his older brother Zoltan had survived the camps only to be hung from a tree by Nazi soldiers fleeing the Allied Forces.

Devastated, Ernie fled to the only place a Jew could always call home: the land of Israel.

While in Israel, he married his wife on a rooftop in Haifa with only $3 to finance their entire ceremony. It was Nov. 29, 1947, the same day the United Nations voted for a resolution that would pave the way for the establishment of the modern State of Israel. Before their wedding ceremony was over, war had broken out. Ernie ran off to join the fight.

The Hollander’s wedding in Haifa

The Hollander’s wedding in Haifa

He served in the Irgun and battled in the Israeli War of Independence. He was wounded three times but he never turned back, even when his wife telegraphed him that their daughter Beverly had been born. Eventually, they left Israel and moved to California. Together, they opened a bakery selling Hungarian strudel in the Jewish shtetl of Oakland. He spoke with a thick accent, loved Yiddish, and referred to God as “Oybeshter“, the One above”.

Although he loved the smiles of people who frequented his bakery, his real passion was educating young people about the Holocaust at universities, churches and high schools all over the Bay Area. In 1991, Hollander received an invitation to debate a Holocaust denier on “The Montel Williams Show.” Many felt that Ernie shouldn’t give the guy the light of day. But Ernie was not one to turn away from a fight and went anyway.

No one could have ever imagined what would happen next.

TV stations came to film the debate. It was broadcast all over the country. Ernie didn’t care about all that. He was just happy that he was able to put this guy in his place. The audience must have agreed as they gave Ernie a resounding applause. But thousands of miles away in New York, there was a man named Zika sitting on his couch flipping through the channels. At that exact moment, he flipped to the debate. As he looked at the Holocaust survivor on TV, he rubbed his eyes in disbelief.

It can’t be! he thought. This survivor in California is the spitting image of my friend from Serbia. How is this possible?

Zika picked up the phone and called the number for the Montel Williams show. Through frantic rambling, he told the producers of the show that the impossible had happened. Ernie’s long-lost brother Zoltan was still alive!

Zoltan had indeed been hung by the Nazis back in 1944, but they were in such a rush to flee, they didn’t tie the knots well. Zolton fell between the trees and played dead until he could escape. He spent years wandering Europe and eventually settled in Yugoslavia, having believed his entire family had been murdered in the war. For years, he lived alone.

The Montel Williams show hung up on Zika. They were used to calls like this from crazies just wanting money or fame. But Zika wouldn’t give up. He flew to Serbia to tell his friend in person that a Hollander family from California looked a lot like him. Zoltan gave Zika the names of his grandparents, parents, brothers and sisters along with their birthdays. When Zika returned to New York, he mailed that information to The Montel Williams Show.

After receiving the letter, someone from the show telephoned the Hollander’s in Oakland, California. Ernie wasn’t home. But his beloved wife Anna was. She didn’t believe it. “But we have a memorial plaque for Zoltan at Beth Jacob?” She didn’t want to get her husband’s hopes up, only for them to be dashed if it turned out to be a hoax. “But how else would this man in Serbia know all the intimate details of Ernie’s family?” She called Rabbi Zack, the spiritual leader of their synagogue.

The rabbi advised her to tell Ernie. He suggested she not be alone. Several neighbors came over to be with her. When Ernie finally came through the door, she told him to sit down because she had some good news for him and then ran to the kitchen. He heard her sobbing. Ernie followed her inside the kitchen, put his arms around her and asked, “If this is such good news, why are you crying and why do I have to sit down?”

Moments later, everyone in the room was crying. Ernie picked up the phone and called Serbia. For the first time in 52 years, he spoke to his brother Heshy [aka Zoltan]. They spoke for hours. They spoke on the phone every day until The Montel Williams show flew Zoltan from Serbia to Oakland to televise the reunion on live TV.

Ernie waited next to his wife on stage, proudly wearing his yarmulke, with his right hand flitting nervously near his wife’s hand. Finally, the announcer let Zoltan enter the room. Their eyes met and the brothers ran to embrace each other. Millions of viewers wept.

My father told me that Ernie told everyone in shul that having his brother, whom he had thought was dead for 50 years, reunited with him was the “the greatest miracle since Moses crossed the sea.”

But as a kid, I didn’t know any of this.

For me, Ernie was just the jolly roly-poly “Gabbai” (“sexton”) of the shul who always smiled and gave me candy when I came to services. He’d pinch my cheeks and make jokes to make me laugh. I will never forget the reverence and solemn deference which my father always showed Ernie. He taught me and my siblings to do the same.

There are still “Kedoshim” who walk among us. Now, more than ever, we need their wisdom. We need their story. They make the world sweeter than the sweetest candy.