by Robert Ellsberg: Far ahead of his time, Pierre Teilhard anticipated the birth of a global web of consciousness: We must all go forward together in love, while still preserving individuality, or we will perish. “ We have reached a crossroads in human evolution where the only road which leads forward is towards a common passion,” he wrote. “To continue to place our hopes in a social order achieved by external violence would simply amount to our giving up all hope of carrying the Spirit of the Earth to its limits.” Teilhard recognized that change does not happen in an instant. Before we can realize our potential as human beings, we need to experiment with different ways, suffer labor pangs, and sometimes even backtrack. But Teilhard’s confidence that we can be — and will be — more loving, cooperative, and conscious than we are now remains a steady source of hope.

We have reached a crossroads in human evolution where the only road which leads forward is towards a common passion,” he wrote. “To continue to place our hopes in a social order achieved by external violence would simply amount to our giving up all hope of carrying the Spirit of the Earth to its limits.” Teilhard recognized that change does not happen in an instant. Before we can realize our potential as human beings, we need to experiment with different ways, suffer labor pangs, and sometimes even backtrack. But Teilhard’s confidence that we can be — and will be — more loving, cooperative, and conscious than we are now remains a steady source of hope.

— Patricia Carlson

“I want to teach people how to see God everywhere, to see Him in all that is most hidden, most solid, and most ultimate in the world.”

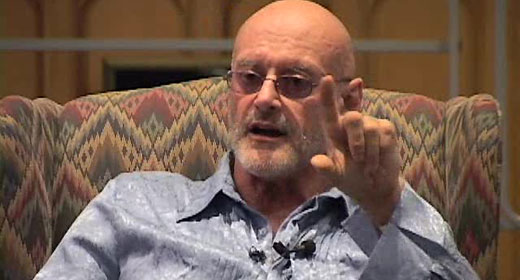

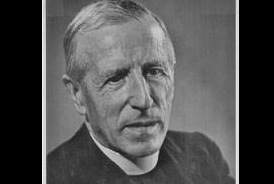

The work of the French Jesuit Pierre Teilhard de Chardin lies behind many of the most creative movements in contemporary theology and spirituality. He was a prophet who labored hard to reconcile the language of science and the language of religion. He was a mystic, afire with a vision of the divine mystery at the heart of the cosmos. He was also a man of profound faith who epitomized a spirituality of engagement in the world and its deepest questions.

Yet little of this was recognized in his life. Throughout his career he was denied permission by Rome and his religious superiors to publish any of his theological or philosophical writings, to lecture publicly, or even to accept any significant academic appointments. Such treatment caused him severe frustration and suffering. Yet he submitted in obedience, convinced that he served Christ best by faithfulness to his vocation. “The more the years pass, the more I begin to think that my function is probably simply that…of John the Baptist, that is, of one who presages what is to come. Or perhaps what I am called on to do is simply to help in the birth of a new soul in that which already is.”

Teilhard was born on May 1, 1881, to a large family of noble lineage. The volcanic hills that surrounded his home in the Auvergne region of France stimulated a childhood fascination with rocks and fossils. He maintained this enthusiasm after entering the Jesuits at the age of eighteen. Thereafter his theological studies were pursued in tandem with research in geology and paleontology.

Teilhard went on to become a scientist of the first rank. He published over a hundred scholarly articles and took part in excavations on three continents. He was part of the team that discovered the remains of “Peking Man,” at that time the oldest human ancestor on record. But all the while he was working out a profound theological synthesis, integrating the theory of evolution with his own cosmic vision of Christianity.

According to Teilhard the history of the earth reflected a gradual unfolding of the potentialities of matter and energy. Inanimate matter gave way to life; simple life forms gave way to ever-more complex organisms. All this culminated in human consciousness. But was this the final terminus of evolution? Teilhard believed the process must continue, though now across the threshold of consciousness. Where was the destination of this process? Teilhard called it the Omega Point — the horizon in which spirit and matter must eventually converge. As a Christian, he identified this Omega with Christ, the beginning and end of history. In Jesus, God-made-flesh, we had a guarantee of our ultimate destiny. Here the spirit of God and the principle of matter were definitively joined.

Teilhard’s spirituality was marked by a strong apprehension of the Incarnation. With a mystic’s eye he perceived the face of the divine in all of creation. In part this vision was forged in the midst of death, while he served courageously as a stretcher-bearer during World War I. He later described an experience that had occurred as he sat in a chapel near the battlefield of Verdun, meditating on the consecrated host. It seemed as if the energy of God’s incarnate love expanded to fill the room, and ultimately to encompass the battlefield and the entire universe. For Teilhard, as for the Jesuit Gerard Manley Hopkins, the world was “charged with the grandeur of God.” Similarly, in a “Hymn to Matter,” he wrote,

Blessed be you, harsh matter, barren soil, stubborn rock: you who yield only to violence, you would force us to work if we would eat….Blessed be you, mortal matter! Without you, without your onslaughts, without your uprootings of us, we should remain ignorant of ourselves and of God.

Teilhard spent the years 1923 to 1946 doing research and field work in China. The assignment was a kind of exile, the result of his superiors’ desire to keep him far from the theological limelight in Europe. But it was there that he worked out his most mature thought. He was thrilled with the idea that through work in the world human beings were participating in the ongoing extension and consecration of God’s creation. This insight was especially nourished by his devotion to the Eucharist. But many times while on the road he lacked the requirements for Mass. Thus, he was inspired to write his “mass on the world.”

Since once again, Lord,…I have neither bread nor wine nor altar I will raise myself beyond these symbols, up to the pure majesty of the real itself; I, your priest, will make the whole earth my altar and on it will offer you all the labors and suffering of the world.

Copies of Teilhard’s writings were passed from hand to hand among a select audience of friends and fellow Jesuits. But he was repeatedly denied permission to have them published. Although he was never formally condemned, his career was continuously frustrated and clouded by the disapproval of Rome. His work might have disappeared altogether if Teilhard had not taken the mildly rebellious precaution of naming a laywoman friend as his literary executor. To this initiative was due Teilhard’s posthumous fame and influence. Teilhard’s last “exile” was to the United States, where he spent his final years in New York. He once noted, “I should like to die on the day of the Resurrection.” So it came to pass. He was felled by a heart attack and died on April 10, 1955, Easter Sunday. In dying, his vision was at last released to the world:

The day will come when, after harnessing the ether, the winds, the tides, and gravitation, we will harness for God the energies of love. And on that day, for the second time in the history of the world, man will have discovered fire.