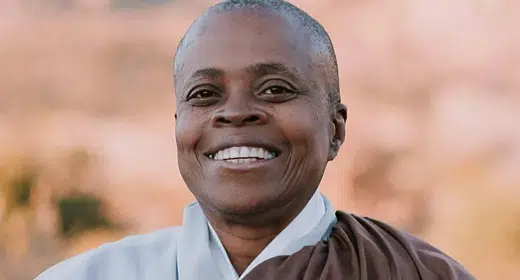

by Myra Goodman: Soto Zen Buddhist Priest Zenju Earthlyn Manuel wades through the muck of racism, sexism, and homophobia to empower practitioners…

Zenju Earthlyn Manuel is not your typical Soto Zen Buddhist priest. She’s an African-American author, poet, diviner, and medicine woman of the drum whose practices are influenced by Native American and African indigenous traditions. The revelations she shares in The Shamanic Bones of Zen: Revealing the Ancestral Spirit and Mystical Heart of a Sacred Tradition are equally unique.

Manuel describes how Soto Zen meditation, chanting, and ritual opened a channel between her and “the voice of the earth”—a direct experience which revealed Zen’s indigenous roots and “shamanic bones.” She believes that widening our perspective on Zen Buddhist teachings will help lift the veil on who we are as living beings, ripen our transmissions, and “return us to the earth, to the root of all religions and spiritual paths.”

Manuel says that embracing Zen without taking steps to honor the bones of the ancestors in the lineage is a form of appropriation. With appropriation, “we don’t see the practice as one of enhancing interrelationship but one of personal improvement … And we don’t see that there is an opportunity in ritual and ceremony to activate justice through collective awakening with the help of ancestors or who or what were here before our birth.” Coming to Zen, Manuel wrote, “… was as if Buddha, a great ancestor, was whispering to me all-day long.”

S&H: You emphasize that Zen is an embodied practice—how true awakening comes through the body, not through texts or intellectual teachings.

You wrote, “We can relax the mind. We don’t need to figure everything out. In a shamanic way, we can allow the practice to work on us rather than working the practice.” Can you explain this a bit more?

Zenju Earthlyn Manuel: For me, the most important part of being a Zen dharma transmitted teacher is to be a guide—to walk with people in ceremony, not try to teach them with words. Talk isn’t the practice. What matters is what happens to people when they bow, when they chant, and when they sit. I want them to follow their own body. That teaching is unspoken, and how one person experiences it isn’t necessarily how someone else will. When students are listening to my words, they’re processing with their minds, not their bodies.

Studying Zen isn’t the practice. Doing it can be an amazing thing. I want my students to follow their body—to follow Zen, not Zenju.

[Read: “How to Embody Kindness.”]

You wrote that coming to San Francisco Zen Center, you found “a Zen of the earth, deep in the muck of human conditions including racism, sexism, and homophobia,” and that systemic oppression can be found in every religious tradition, institution, and spiritual community in the United States. Can you explain what you meant when you described oppression as “the soil by which we are given to dig out liberation every moment, in an endless garden.”

The point I wanted to make is that it was the ceremonies that transformed me, regardless of the muck. I brought my muck to Zen, as did everyone else. I had the same tears at the Zen center as I did outside. You can’t escape oppression because it’s everywhere. You can’t oppress oppression. But now I am able to engage that suffering from a liberated tenderness and not from woundedness. It’s that liberated tenderness that allows me to use this muck—to take it, hold it, and taste it so that I can see what mindset is in it that needs liberating.

I brought my muck to Zen, as did everyone else.

Right now, a lot of people are feeling so much oppression in our world. I always tell my students that it’s powerful to walk in the middle of that oppression—to offer incense in the middle of it, to bow in the middle of it, to chant in the middle of it. Through Zen practice, the true nature of the self is exposed. It was in the silence of sitting that I began to see that my own blackness and my own queerness is evolutionary. It’s not static and it has nothing to do with what anyone else says it is.

Through the rituals of Zen, my students are having a direct experience of liberation within oppression.

Are you saying that you welcome the opportunity to work with the muck of this world?

When trouble happens, it’s sacred time. There’s a fire, but there’s always a fire at the door. Always. You’ve got to be right with the fire instead of leaving to look for water. Whether you like it or not, it doesn’t matter, because whatever it is, it’s still happening. So, when trouble is happening, walk slower. Be quieter. These are sacred moments that are magical, mystical and illuminating.

[Read: “Shhh … A Silent Retreat Guide.”]

These sacred unsettling moments are not to be feared, even though we usually fear them because we’re human, and that’s okay too. Fear and rage are also mystical and magical. They’re all part of it.

Some people focus too much on finding the lesson in the suffering. That can cut short the journey of what the darkness is doing with you. Just allow it to take its time, not your time. Don’t try to turn the grief around quickly. Let it do its work.

You wrote, “By participating in Zen rituals and ceremonies, there was a strong sense in me that something had been suppressed in the transmission of the practice. This strong sense brought me even closer to the practice. I wondered: If the shamanic bones or the indigenous roots that were suppressed in the rising of Buddhism were unearthed, would the practice make more sense to practitioners, especially to black, indigenous, and people of color?”

Are you finding this to be true?

In 2014, I founded Still Breathing Zen Meditation Center in Oakland. Everyone was welcome—in fact, I needed experienced people to help with the ceremonies and chants—but seasoned Zen practitioners living in Oakland didn’t come. The unsupported center quickly closed. The then racially-mixed sangha continued in my home. In 2017, with the rise of anti-blackness, some members requested that the sangha be a refuge for black people only. Those who weren’t black departed with great understanding. There were tears. We currently are a small private Zen sangha for black people that meets on Zoom—still chanting, ringing bells, bowing, and still breathing.

The book shares how I felt officiating at the first Jukai (lay initiation ceremony) for my black students:

I saw that the transmission wasn’t about me. Through my tears, I saw my black students move with so much courage in a ceremony unfamiliar to them—hand-in-hand, heart-to-heart, into full liberation. Not liberation from something but liberation into being the body of nature, being the earth that they are.

It’s a long process to prepare for Jukai, and I didn’t think my students would want to do it, but they did.

What advice do you give people who are searching for a spiritual practice and are considering Zen?

Zen is hard for anyone to understand if looking in from the outside. Direct engagement with the rituals and ceremonies is what makes Zen an experience of Buddha’s teachings. That’s why I wrote, “Chanting is a powerful way to experience oneness. To merge our many voices as one sound is to join together in an intimate way as we do with our breath in sitting together. There is one mind, one heart.”

I always tell people to consider the teachings as if you just met someone new and you want to know them. Maybe they will become your beloved, and maybe not. You meet them, something draws you in, and then you start walking and living with those teachings. Usually you have to walk a long time with a new beloved. It might take your entire life to know them.

I always tell people to consider the teachings as if you just met someone new and you want to know them.

You don’t need 50,000 beloveds. I always tell people to pick just one or two teachings and really walk with those. I chose Zen because engaging in zazen meditation, ritual and ceremony allows me to be a conduit for the wisdom that’s needed for this life.