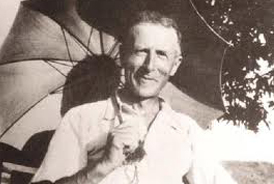

by Jennifer Cobb Kreisberg: An obscure Jesuit priest, Pierre Teilhard de Chardin, set down the philosophical framework for planetary, Net-based consciousness 50 years ago.

He has inspired Al Gore and Mario Cuomo. Cyberbard John Perry Barlow finds him richly prescient. Nobel laureate Christian de Duve claims his vision helps us find meaning in the cosmos. Even Marshall McLuhan cited his “lyrical testimony” when formulating his emerging global-village vision. Whom is this eclectic group celebrating? An obscure Jesuit priest and paleontologist named Pierre Teilhard de Chardin, whose quirky philosophy points, oddly, right into cyberspace.

He has inspired Al Gore and Mario Cuomo. Cyberbard John Perry Barlow finds him richly prescient. Nobel laureate Christian de Duve claims his vision helps us find meaning in the cosmos. Even Marshall McLuhan cited his “lyrical testimony” when formulating his emerging global-village vision. Whom is this eclectic group celebrating? An obscure Jesuit priest and paleontologist named Pierre Teilhard de Chardin, whose quirky philosophy points, oddly, right into cyberspace.

Teilhard de Chardin finds allies among those searching for grains of spiritual truth in a secular universe. As Mario Cuomo put it, “Teilhard made negativism a sin. He taught us how the whole universe – even pain and imperfection – is sacred.” Marshall McLuhan turned to Teilhard as a source of divine insight in The Gutenberg Galaxy, his classic analysis of Western culture’s descent into a profane world. Al Gore, in his book Earth in the Balance, argues that Teilhard helps us understand the importance of faith in the future. “Armed with such faith,” Gore writes, “we might find it possible to resanctify the earth, identify it as God’s creation, and accept our responsibility to protect and defend it.”

From the ’20s to the ’50s, Teilhard de Chardin drafted a series of poetic works about evolution that has reemerged as a foundation for new evolutionary theories. In particular, Teilhard and his Russian counterpart Vladimir Vernadsky inspired the renegade Gaia hypothesis (later set forth by James Lovelock and Lynn Margulis): the global ecosystem is a superorganism with a whole much greater than the sum of its parts. This vision is clearly theological – suddenly everything, from rocks to people, takes on a holistic importance. As a Jesuit, Teilhard felt this deeply, and a handful of cyberphilosophers are now mining this ideological source as they search for the deeper implications of the Net. As Barlow says, “Teilhard’s work is about creating a consciousness so profound it will make good company for God itself.”

Teilhard imagined a stage of evolution characterized by a complex membrane of information enveloping the globe and fueled by human consciousness. It sounds a little off-the-wall, until you think about the Net, that vast electronic web encircling the Earth, running point to point through a nervelike constellation of wires. We live in an intertwined world of telephone lines, wireless satellite-based transmissions, and dedicated computer circuits that allow us to travel electronically from Des Moines to Delhi in the blink of an eye.

Teilhard saw the Net coming more than half a century before it arrived. He believed this vast thinking membrane would ultimately coalesce into “the living unity of a single tissue” containing our collective thoughts and experiences. In his magnum opus, The Phenomenon of Man, Teilhard wrote, “Is this not like some great body which is being born – with its limbs, its nervous system, its perceptive organs, its memory – the body in fact of that great living Thing which had to come to fulfill the ambitions aroused in the reflective being by the newly acquired consciousness?”

“What Teilhard was saying here can easily be summed up in a few words,” says John Perry Barlow. “The point of all evolution up to this stage is the creation of a collective organism of Mind.”

Teilhard’s philosophy of evolution was born out of his duality as both a Jesuit father ordained in 1911 and a paleontologist whose career began in the early 1920s. While conducting research in the Egyptian desert, Teilhard was scratching around for the remains of ancient creatures when he turned over a stone, dusted it off, and suddenly realized that everything around him was beautifully connected in one vast, pulsating web of divine life. Teilhard soon developed a philosophy that married the science of the material world with the sacred forces of the Catholic Church. Neither the Catholic Church nor the scientific academy, however, agreed. Teilhard’s premise, that rocks possessed a divine force, was seen as flaky by scientists and outright heretical by the church. Teilhard’s writings were scorned by peers in both camps.