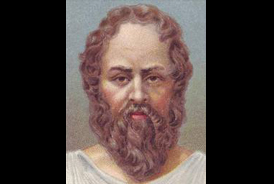

by Bettany Hughes: Two thousand four hundred years ago, one man tried to discover the meaning of life.

Socrates search was so radical, charismatic and counterintuitive that he become famous throughout the Mediterranean. Men – particularly young men – flocked to hear him speak. Some were inspired to imitate his ascetic habits. They wore their hair long, their feet bare, their cloaks torn. He charmed a city; soldiers, prostitutes, merchants, aristocrats – all would come to listen. As Cicero eloquently put it, “He brought philosophy down from the skies.”

Socrates search was so radical, charismatic and counterintuitive that he become famous throughout the Mediterranean. Men – particularly young men – flocked to hear him speak. Some were inspired to imitate his ascetic habits. They wore their hair long, their feet bare, their cloaks torn. He charmed a city; soldiers, prostitutes, merchants, aristocrats – all would come to listen. As Cicero eloquently put it, “He brought philosophy down from the skies.”

For close on half a century this man was allowed to philosophise unhindered on the streets of his hometown. But then things started to turn ugly. His glittering city-state suffered horribly in foreign and civil wars. The economy crashed; year in, year out, men came home dead; the population starved; the political landscape was turned upside down. And suddenly the philosopher’s bright ideas, his eternal questions, his eccentric ways, started to jar. And so, on a spring morning in 399BC, the first democratic court in the story of mankind summoned the 70-year-old philosopher to the dock on two charges: disrespecting the city’s traditional gods and corrupting the young. The accused was found guilty. His punishment: state-sponsored suicide, courtesy of a measure of hemlock poison in his prison cell.

The man was Socrates, the philosopher from ancient Athens and arguably the true father of western thought. Not bad, given his humble origins. The son of a stonemason, born around 469BC, Socrates was famously odd. In a city that made a cult of physical beauty (an exquisite face was thought to reveal an inner nobility of spirit) the philosopher was disturbingly ugly. Socrates had a pot-belly, a weird walk, swivelling eyes and hairy hands. As he grew up in a suburb of Athens, the city seethed with creativity – he witnessed the Greek miracle at first-hand. But when poverty-striken Socrates (he taught in the streets for free) strode through the city’s central marketplace, he would harrumph provocatively, “How many things I don’t need!”

Whereas all religion was public in Athens, Socrates seemed to enjoy a peculiar kind of private piety, relying on what he called his “daimonion“, his “inner voice”. This “demon” would come to him during strange episodes when the philosopher stood still, staring for hours. We think now he probably suffered from catalepsy, a nervous condition that causes muscular rigidity.

Putting aside his unshakable position in the global roll-call of civilisation’s great and good, why should we care about this curious, clever, condemned Greek? Quite simply because Socrates’s problems were our own. He lived in a city-state that was for the first time working out what role true democracy should play in human society. His hometown – successful, cash-rich – was in danger of being swamped by its own vigorous quest for beautiful objects, new experiences, foreign coins.

The philosopher also lived through (and fought in) debilitating wars, declared under the banner of demos-kratia – people power, democracy. The Peloponnesian conflict of the fifth century against Sparta and her allies was criticised by many contemporaries as being “without just cause”. Although some in the region willingly took up this new idea of democratic politics, others were forced by Athens to love it at the point of a sword. Socrates questioned such blind obedience to an ideology. “What is the point,” he asked, “of walls and warships and glittering statues if the men who build them are not happy?” What is the reason for living life, other than to love it?

For Socrates, the pursuit of knowledge was as essential as the air we breathe. Rather than a brainiac grey-beard, we should think of him as his contemporaries knew him: a bustling, energetic, wine-swilling, man-loving, vigorous, pug-nosed, sword-bearing war-veteran: a citizen of the world, a man of the streets.

According to his biographers Plato and Xenophon, Socrates did not just search for the meaning of life, but the meaning of our own lives. He asked fundamental questions of human existence. What makes us happy? What makes us good? What is virtue? What is love? What is fear? How should we best live our lives? Socrates saw the problems of the modern world coming; and he would certainly have something to say about how we live today.

He was anxious about the emerging power of the written word over face-to-face contact. The Athenian agora was his teaching room. Here he would jump on unsuspecting passersby, as Xenophon records. “One day Socrates met a young man on the streets of Athens. ‘Where can bread be found?’ asked the philosopher. The young man responded politely. ‘And where can wine be found?’ asked Socrates. With the same pleasant manner, the young man told Socrates where to get wine. ‘And where can the good and the noble be found?’ then asked Socrates. The young man was puzzled and unable to answer. ‘Follow me to the streets and learn,’ said the philosopher.”

Whereas immediate, personal contact helped foster a kind of honesty, Socrates argued that strings of words could be manipulated, particularly when disseminated to a mass market. “You might think words spoke as if they had intelligence, but if you question them they always say only one thing . . . every word . . . when ill-treated or unjustly reviled always needs its father to protect it,” he said.

When psychologists today talk of the danger for the next generation of too much keyboard and texting time, Socrates would have flashed one of his infuriating “I told you so” smiles. Our modern passion for fact-collection and box-ticking rather than a deep comprehension of the world around us would have horrified him too. What was the point, he said, of cataloguing the world without loving it? He went further: “Love is the one thing I understand.”

The televised election debates earlier this year would also have given pause. Socrates was withering when it came to a polished rhetorical performance. For him a powerful, substanceless argument was a disgusting thing: rhetoric without truth was one of the greatest threats to the “good” society.

Interestingly, the TV debate experiment would have seemed old hat. Public debate and political competition (agon was the Greek word, which gives us our “agony”) were the norm in democratic Athens. Every male citizen over the age of 18 was a politician. Each could present himself in the open-air assembly up on the Pnyx to raise issues for discussion or to vote. Through a complicated system of lots, ordinary men might be made the equivalent of heads of state for a year; home secretary or foreign minister for the space of a day. Those who preferred a private to a public life were labelled idiotes (hence our word idiot).

Socrates died when Golden Age Athens – an ambitious, radical, visionary city-state – had triumphed as a leader of the world, and then over-reached herself and begun to crumble. His unusual personal piety, his guru-like attraction to the young men of the city, suddenly seemed to have a sinister tinge. And although Athens adored the notion of freedom of speech (the city even named one of its warships Parrhesia after the concept), the population had yet to resolve how far freedom of expression ratified a freedom to offend.

Socrates was, I think, a scapegoat for Athens’s disappointment. When the city was feeling strong, the quirky philosopher could be tolerated. But, overrun by its enemies, starving, and with the ideology of democracy itself in question, the Athenians took a more fundamentalist view. A confident society can ask questions of itself; when it is fragile, it fears them. Socrates’s famous aphorism “the unexamined life is not worth living” was, by the time of his trial, clearly beginning to jar.

After his death, Socrates’s ideas had a prodigious impact on both western and eastern civilisation. His influence in Islamic culture is often overlooked – in the Middle East and North Africa, from the 11th century onwards, his ideas were said to refresh and nourish, “like . . . the purest water in the midday heat”. Socrates was nominated one of the Seven Pillars of Wisdom, his nickname “The Source”. So it seems a shame that, for many, Socrates has become a remote, lofty kind of a figure.

When Socrates finally stood up to face his charges in front of his fellow citizens in a religious court in the Athenian agora, he articulated one of the great pities of human society. “It is not my crimes that will convict me,” he said. “But instead, rumour, gossip; the fact that by whispering together you will persuade yourselves that I am guilty.” As another Greek author, Hesiod, put it, “Keep away from the gossip of people. For rumour [the Greek pheme, via fama in Latin, gives us our word fame] is an evil thing; by nature she’s a light weight to lift up, yes, but heavy to carry and hard to put down again. Rumour never disappears entirely once people have indulged her.”

Trial by media, by pheme, has always had a horrible potency. It was a slide in public opinion and the uncertainty of a traumatised age that brought Socrates to the hemlock. Rather than follow the example of his accusers, we should perhaps honour Socrates’s exhortation to “know ourselves”, to be individually honest, to do what we, not the next man, knows to be right. Not to hide behind the hatred of a herd, the roar of the crowd, but to aim, hard as it might be, towards the “good” life.