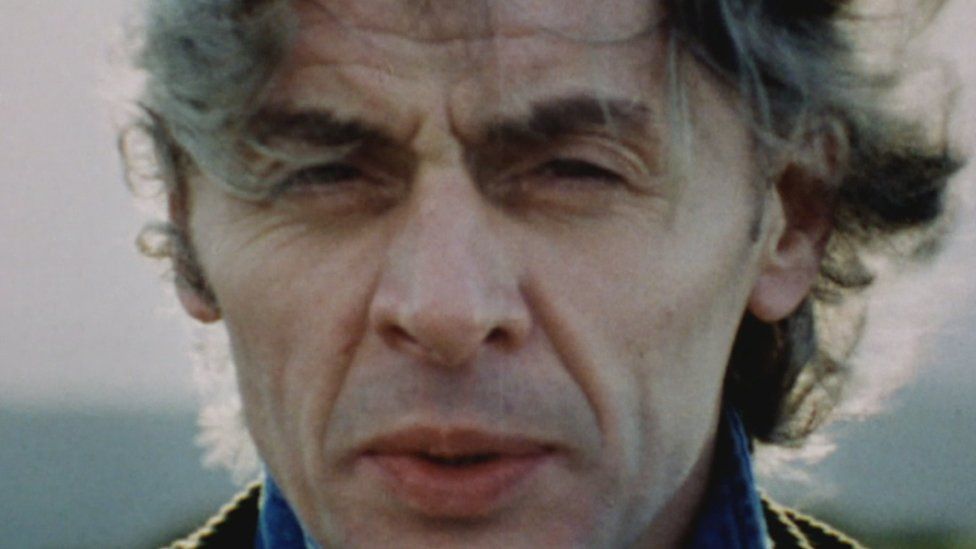

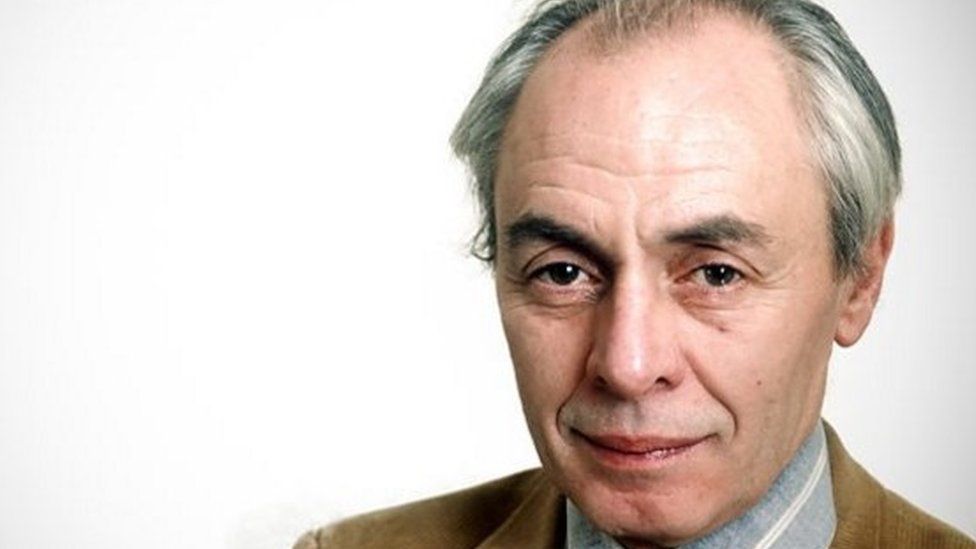

by Steven Brocklehurst: RD Laing was not only Scotland’s most famous psychiatrist but for a period in the 1960s he was one of the most famous therapists in the world…

At his peak he was revered as the “high priest of anti-psychiatry”, famous for his bestselling books and celebrity friends such as Sean Connery, who Laing is said to have treated for stress by introducing the James Bond actor to psychedelic drug LSD.

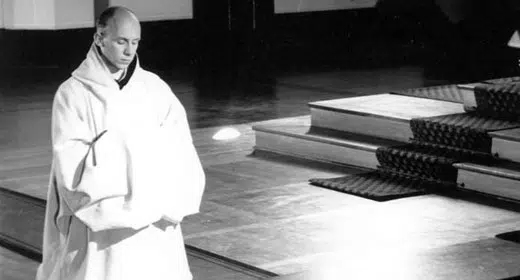

Laing’s boldest experiment was the idealistic “safe haven” for mental health patients that he set up at Kingsley Hall in London’s east end in 1965.

It is the subject of new film Mad To Be Normal, starring Scottish actor David Tennant, which premieres at the Glasgow Film Festival on Sunday.

The therapeutic community Laing set up for people with schizophrenia, which had no locks or traditional heavy duty drugs, attracted visit

It eventually disintegrated into chaos and did much to destroy the psychiatrist’s reputation but many believe it inspired later, less mercurial, psychiatrists to treat patients outside the mental institution.

Ronald David Laing was born in the Govanhill area in the south of Glasgow in 1927.

He went to Hutcheson’s Grammar School and Glasgow University to study medicine and became interested in mental health issues during his National Service in an Army psychiatric unit.

His son Adrian Laing told BBC Radio’s Great Lives programme his father grew up in the “dark ages” of psychiatric treatment, with padded cells, primitive electric shock treatment and lobotomies.

He says that when Laing started in psychiatry in the early 1950s he thought the way patients were being treated was nothing less than “total barbaric behaviour on behalf of the psychiatrist”.

Dr Gavin Miller, senior lecturer in medical humanities at Glasgow University, says Laing was interested in the concept of metanoia.

He says: “It is the idea that psychosis might be some sort of healing journey and the best thing to do was just to let people get on with it in a safe environment.”

In 1955, Laing set up the Rumpus Room experiment at Gartnavel Hospital in Glasgow.

It was an attempt to remove patients with a diagnosis of schizophrenia from the overcrowded and understaffed wards and place them in a more pleasant environment.

The idea was to let them use a large comfortably-furnished room, remove their drugs and give them greater access to nursing support.

After 18 months in the new environment all 12 patients had improved enough to be discharged but a year later they were all back in hospital.

Critics argued this demonstrated schizophrenia was a lifelong condition that could only be marginally improved by environment.

But Laing insisted there was something wrong with the world they were released to outside the hospital.

Very problematic

His experiences at Gartnavel formed the basis of his first book, The Divided Self, which was published in 1960 and became a phenomenon, selling 700,000 copies in the UK alone.

He said he wanted “to make madness and the process of going mad comprehensible”.

A later book Sanity, Madness and the Family drew criticism because it was said to suggest that schizophrenia could be blamed on the parents of patients.

His son Adrian insisted his father had been misquoted and misinterpreted.

Dr Miller says the case studies in the book were “very problematic” and it was hard for psychiatrists to know what to do with them.

He says: “It is not the kind of research that is done very much. It is in-depth, nitty-gritty, personal, small-scale and interpretive.

“The studies are very interesting but I don’t think mainstream psychiatry has understood what to do with them.”

Laing’s outspoken comments, his unusual approach and his lack of proper scientific control groups for his experiments led to major rifts with the establishment.

His drinking and drug use were also causing problems but his superstar status allowed him to put his theories into practice.

In 1965 he founded Kingsley Hall, a safe house where people with schizophrenia could act out their traumas unhindered by conventional morality.

It was underpinned Laing’s philosophy that madness was a self-healing voyage.

He thought that if sufferers were provided with a supportive enough environment they would emerge recovered.

The idea drew international attention and his son Adrian says that therapists came from as far afield as America.

But there was something about the place “that made everyone fall apart”.

This would not have been assisted by claims that Laing would keep LSD in the fridge as a “sort of spiritual laxative” for patients.

Radical psychiatry

Laing’s son says: “There was a very ambiguous line to be drawn between the patients and the therapists because the whole philosophy was to discover yourself through losing yourself.

“The distinction between the patient and therapist just did not exist. Everyone was there for a reason which was a voyage of self-discovery.

“The establishment wanted it closed down. They thought it was liberalism to the point of negligence. It was endangering the lives of the inmates.

“To them it represented the lunatic extreme of radical psychiatry.”

One famous patient was Mary Barnes who had schizophrenia and underwent regression therapy back to her infancy and painted the walls with her faeces.

She later discovered a talent for art becoming a successful painter.

Kingsley Hall continued for five years but was brought to an end after two people jumped off the roof.

Dr Miller says Laing’s reputation declined very sharply through the 70s and 80s.

The psychiatrist died from a heart attack in 1989, at the age of 61.

Dr Miller says: “There was a period towards the end of his career and after his death when the mainstream view would have been to dismiss him as a gadfly, someone who attempted to trouble psychiatry will his various ideas and had been soundly rebuffed and rebutted and repudiated.”

“He was obviously quite a troubled character. He was flamboyant, he was very keen on being a celebrity, he was very provocative and this made his legacy almost too hot to handle.

“It took some distance and time for people to sift through what he was saying and see what might be valuable.”

There are still those who argue that his views on schizophrenia were dangerous nonsense which encouraged patients to stop taking their medication.

However, others recognise his efforts to champion the cause of the mentally ill and his attempt to make madness comprehensible.

Dr Miller says: “When you get into the world of the practising psychiatrist there is a bit more sympathy for Laing because he is actually dealing with patients’ day to day messy reality.”

Mad To Be Normal will be released in cinemas nationwide on 6 April 2017.