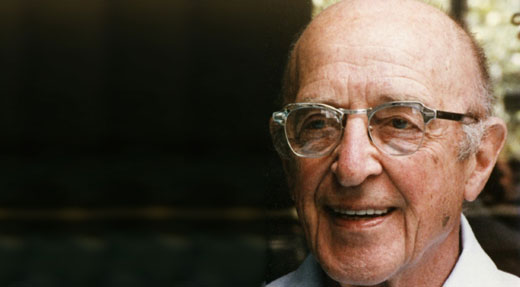

by Carl Rogers: In the autumn of 1964, I was invited to be a speaker in a lecture series at the California Institute of Technology in Pasadena, one of the leading scientific institutions in the world.

Most of the speakers were from the physical sciences. The audience attracted by the series was known to be a highly educated and sophisticated group. The speakers were encouraged to put on demonstrations, if possible, of their subjects, whether astronomy, microbiology, or theoretical physics.

I was asked to speak on the subject of communication.

As I started collecting references and jotting down ideas for the talk, I became very dissatisfied with what I was doing. The thought of a demonstration kept running through my mind, and then being dismissed.

The speech that follows shows how I resolved the problem of endeavoring to communicate, rather than just to speak about the subject of communication.

by Carl Rogers: I have some knowledge about communication and could assemble more. When I first agreed to give this talk, I planned to gather such knowledge and organize it into a lecture. The more I thought over this plan, the less satisfied I was with it. Knowledge about is not the most important thing in the behavioral sciences today. There is a decided surge of experiential knowing, or knowing at a gut level, which has to do with the human being. At this level of knowing, we are in a realm where we are not simply talking of cognitive and intellectual learnings, which can nearly always be rather readily communicated in verbal terms. Instead we are speaking of something more experiential, something having to do with the whole person, visceral reactions and feelings as well as thoughts and words. Consequently, I decided I would like, rather than talking about communication, to communicate with you at a feeling level.

This is not easy. I think it is usually possible only in small groups where one feels genuinely accepted. I have been frightened at the thought of attempting it with a large group. Indeed when I learned how large the group was to be, I gave up the whole idea. Since then, with encouragement from my wife, I have returned to it and decided to make such an attempt.

One of the things which strengthened me in my decision is the knowledge that these Caltech lectures have a long tradition of being given as demonstrations. In any of the usual senses, what follows is not a demonstration. Yet I hope that, in some sense, this may be a demonstration of communication which is given, and also received, primarily at a feeling and experiential level.

What I would like to do is very simple indeed. I would like to share with you some of the things I have learned for myself in regard to communication. These are personal learnings growing out of my own experience. I am not attempting at all to say that you should learn or do these same things but I feel that if I can report my own experience honestly enough, perhaps you can check what I say against your own experience and decide as to its truth or falsity for you.

In my own two-way communication with others there have been experiences that have made me feel pleased and warm and good and satisfied. There have been other experiences that to some extent at the time, and even more so afterward, have made me feel dissatisfied and displeased and more distant and less contented with myself. I would like to convey some of these things. Another way of putting this is that some of my experiences in communicating with others have made me feel expanded, larger, enriched, and have accelerated my own growth. Very often in these experiences I feel that the other person has had similar reactions and that he too has been enriched, that his development and his functioning have moved forward. Then there have been other occasions in which the growth or development of each of us has been diminished or stopped or even reversed. I am sure it will be clear in what I have to say that I would prefer my experiences in communication to have a growth-promoting effect, both on me and on the other, and that I should like to avoid those communication experiences in which both I and the other person feel diminished.

The first simple feeling I want to share with you is my enjoyment when I can really hear someone. I think perhaps this has been a long-standing characteristic of mine. I can remember this in my early grammar school days. A child would ask the teacher a question and the teacher would give a perfectly good answer to a completely different question. A feeling of pain and distress would always strike me. My reaction was, “But you didn’t hear him!” I felt a sort of childish despair at the lack of communication which was (and is) so common.

I believe I know why it is satisfying to me to hear someone. When I can really hear someone, it puts me in touch with him; it enriches my life. It is through hearing people that I have learned all that I know about individuals, about personality, about interpersonal relationships.

There is another peculiar satisfaction in really hearing someone: It is like listening to the music of the spheres, because beyond the immediate message of the person, no matter what that might be, there is the universal. Hidden in all of the personal communications which I really hear there seem to be orderly psychological laws, aspects of the same order we find in the universe as a whole. So there is both the satisfaction of hearing this person and also the satisfaction of feeling one’s self in touch with what is universally true.

When I say that I enjoy hearing someone, I mean, of course, hearing deeply. I mean that I hear the words, the thoughts, the feeling tones, the personal meaning, even the meaning that is below the conscious intent of the speaker. Sometimes too, in a message which superficially is not very important, I hear a deep human cry that lies buried and unknown far below the surface of the person.

So I have learned to ask myself, can I hear the sounds and sense the shape of this other person’s inner world? Can I resonate to what he is saying so deeply that I sense the meanings he is afraid of, yet would like to communicate, as well as those he knows?

I think, for example, of an interview I had with an adolescent boy. Like many an adolescent today he was saying at the outset of the interview that he had no goals. When I questioned him on this, he insisted even more strongly that he had no goals whatsoever, not even one. I said, “There isn’t anything you want to do?”

“Nothing. . . . Well, yeah, I want to keep on living.”

I remember distinctly my feeling at that moment. I resonated very deeply to this phrase. He might simply be telling me that, like everyone else, he wanted to live. On the other hand, he might be telling me – and this seemed to be a definite possibility – that at some point the question of whether or not to live had been a real issue with him. So I tried to resonate to him at all levels. I didn’t know for certain what the message was. I simply wanted to be open to any of the meanings that this statement might have, including the possibility that he might at one time have considered suicide. My being willing and able to listen to him at all levels is perhaps one of the things that made it possible for him to tell me, before the end of the interview, that not long before he had been on the point of blowing his brains out. This little episode is an example of what I mean by wanting to really hear someone at all the levels at which he is endeavoring to communicate.

Let me give another brief example. Not long ago a friend called me long distance about a certain matter. We concluded the conversation and I hung up the phone. Then, and only then, did his tone of voice really hit me. I said to myself that behind the subject matter we were discussing there seemed to be a note of distress, discouragement, even despair, which had nothing to do with the matter at hand. I felt this so sharply that I wrote him a letter saying something to this effect:

“I may be all wrong in what I am going to say and if so, you can toss this in the wastebasket, but I realized after I hung up the phone that you sounded as though you were in real distress and pain, perhaps in real despair.” Then I attempted to share with him some of my own feelings about him and his situation in ways that I hoped might be helpful. I sent off the letter with some qualms, thinking that I might have been ridiculously mistaken. I very quickly received a reply. He was extremely grateful that someone had heard him. I had been quite correct in hearing his tone of voice and I felt very pleased that I had been able to hear him and hence make possible a real communication. So often, as in this instance, the words convey one message and the tone of voice a sharply different one.

I find, both in therapeutic interviews and in the intensive group experiences which have meant a great deal to me, that hearing has consequences. When I truly hear a person and the meanings that are important to him at that moment, hearing not simply his words, but him, and when I let him know that I have heard his own private personal meanings, many things happen. There is first of all a grateful look. He feels released. He wants to tell me more about his world. He surges forth in a new sense of freedom. He becomes more open to the process of change.

I have often noticed that the more deeply I hear the meanings of this person, the more there is that happens. Almost always, when a person realizes he has been deeply heard, his eyes moisten. I think in some real sense he is weeping for joy. It is as though he were saying, “Thank God, somebody heard me. Someone knows what it’s like to be me.” In such moments I have had the fantasy of a prisoner in a dungeon, tapping out day after day a Morse code message, “Does anybody hear me? Is anybody there?” And finally one day he hears some faint tappings which spell out “Yes.” By that one simple response he is released from his loneliness; he has become a human being again. There are many, many people living in private dungeons today, people who give no evidence of it whatsoever on the outside, where you have to listen very sharply to hear the faint messages from the dungeon.

If this seems to you a little too sentimental or overdrawn, I would like to share with you an experience I had recently in a basic encounter group with fifteen persons in important executive posts. Early in the very intensive sessions of the week they were asked to write a statement of some feeling or feelings which they were not willing to share with the group. These were anonymous statements. One man wrote, “I don’t relate easily to people. I have an almost impenetrable facade. Nothing gets in to hurt me but nothing gets out. I have repressed so many emotions that I am close to emotional sterility. This situation doesn’t make me happy, but I don’t know what to do about it. Perhaps insight into how others react to me and why will help.” This was clearly a message from a dungeon. Later in the week a member of the group identified himself as the man who had written that anonymous message, filling out in much greater detail his feelings of isolation, of complete coldness. He felt that life had been so brutal to him that he had been forced to live a life without feeling, not only at work but also in social groups and, saddest of all, with his family. His gradual achievement of greater expressiveness in the group, of less fear of being hurt, of more willingness to share himself with others, was a very rewarding experience for all of us who participated.

I was both amused and pleased when, in a letter a few weeks later asking me about another matter, he also included this paragraph: “When I returned from [our group] I felt somewhat like a young girl who had been seduced, but still wound up with the feeling that it was exactly what she had been waiting for and needed! I am still not quite sure who was responsible for the seduction – you or the group, or whether it was a joint venture. I suspect it was the latter. At any rate, I want to thank you for what was a meaningful and intensely interesting experience.” I think it is not too much to say that because several of us in the group were able genuinely to hear him, he was released from his dungeon and came out, at least to some degree, into the sunnier world of warm interpersonal relationships.

Let me move on to a second learning that I would like to share with you. I like to be heard. A number of times in my life I have felt myself bursting with insoluble problems, or going round and round in tormented circles or, during one period, overcome by feelings of worthlessness and despair. I think I have been more fortunate than most in finding, at these times, individuals who have been able to hear me and thus to rescue me from the chaos of my feelings, individuals who have been able to hear my meanings a little more deeply than I have known them. These persons have heard me without judging me, diagnosing me, appraising me, evaluating me. They have just listened and clarified and responded to me at all the levels at which I was communicating. I can testify that when you are in psychological distress and someone really hears you without passing judgment on you, without trying to take responsibility for you, without trying to mold you, it feels damn good! At these times it has relaxed the tension in me. It has permitted me to bring out the frightening feelings, the guilts, the despair, the confusions that have been a part of my experience. When I have been listened to and when I have been heard, I am able to re-perceive my world in a new way and to go on. It is astonishing how elements that seem insoluble become soluble when someone listens, how confusions that seem irremediable turn into relatively clear flowing streams when one is heard. I have deeply appreciated the times that I have experienced this sensitive, empathic, concentrated listening.

|

I dislike it in myself when I can’t hear another, when I do not understand him. If it is only a simple failure of comprehension or a failure to focus my attention on what he is saying or a difficulty in understanding his words, then I feel only a very mild dissatisfaction with myself. But what I really dislike in myself is not being able to hear the other person because I am so sure in advance of what he is about to say that I don’t listen. It is only afterward that I realize that I have heard what I have already decided he is saying; I have failed really to listen. Or even worse are those times when I catch myself trying to twist his message to make it say what I want him to say, and then only hearing that. This can be a very subtle thing, and it is surprising how skillful I can be in doing it. Just by twisting his words a small amount, by distorting his meaning just a little, I can make it appear that he is not only saying the thing I want to hear, but that he is the person I want him to be. Only when I realize through his protest or through my own gradual recognition that I am subtly manipulating him, do I become disgusted with myself. I know too, from being on the receiving end of this, how frustrating it is to be received for what you are not, to be heard as saying something which you have not said. This creates anger and bafflement and disillusion.

This last statement indeed leads into the next learning that I want to share with you: I am terribly frustrated and shut into myself when I try to express something which is deeply me, which is a part of my own private, inner world, and the other person does not understand. When I take the gamble, the risk, of trying to share something that is very personal with another individual and it is not received and not understood, this is a very deflating and a very lonely experience. I have come to believe that such an experience makes some individuals psychotic. It causes them to give up hoping that anyone can understand them. Once they have lost that hope, then their own inner world, which becomes more and more bizarre, is the only place where they can live. They can no longer live in any shared human experience. I can sympathize with them because I know that when I try to share some feeling aspect of myself which is private, precious, and tentative, and when this communication is met by evaluation, by reassurance, by distortion of my meaning, my very strong reaction is, “Oh, what’s the use!” At such a time, one knows what it is to be alone.

So, as you can readily see from what I have said thus far, a creative, active, sensitive, accurate, empathic, nonjudgmental listening is for me terribly important in a relationship. It is important for me to provide it; it has been extremely important, especially at certain times in my life, to receive it. I feel that I have grown within myself when I have provided it; I am very sure that I have grown and been released and enhanced when I have received this kind of listening.

Let me move on to another area of my learnings.

I find it very satisfying when I can be real, when I can be close to whatever it is that is going on within me. I like it when I can listen to myself. To really know what I am experiencing in the moment is by no means an easy thing, but I feel somewhat encouraged because I think that over the years I have been improving at it. I am convinced, however, that it is a lifelong task and that none of us ever is totally able to be comfortably close to all that is going on within our own experience.

In place of the term “realness” I have sometimes used the word “congruence.” By this I mean that when my experiencing of this moment is present in my awareness and when what is present in my awareness is present in my communication, then each of these three levels matches or is congruent. At such moments I am integrated or whole, I am completely in one piece. Most of the time, of course, I, like everyone else, exhibit some degree of incongruence. I have learned, however, that realness, or genuineness, or congruence – whatever term you wish to give it – is a fundamental basis for the best of communication.

What do I mean by being close to what is going on in me? Let me try to explain what I mean by describing what sometimes occurs in my work as a therapist. Sometimes a feeling “rises up in me” which seems to have no particular relationship to what is going on. Yet I have learned to accept and trust this feeling in my awareness and to try to communicate it to my client. For example, a client is talking to me and I suddenly feel an image of him as a pleading little boy, folding his hands in supplication, saying, “Please let me have this, please let me have this.” I have learned that if I can be real in the relationship with him and express this feeling that has occurred in me, it is very likely to strike some deep note in him and to advance our relationship.

Let me give another example. It is often very hard for me, as for other writers, to get close to my self when I start to write. It is so easy to be distracted by the possibility of saying things which will catch approval or will look good to colleagues or make a popular appeal. How can I listen to the things that I really want to say and write? It is difficult. Sometimes I even have to trick myself to get close to what is in me. I tell myself that I am not writing for publication; I am just writing for my own satisfaction. I write on old scraps of paper so that I don’t even have to reproach myself for wasting paper. I jot down feelings and ideas as they come, helter-skelter, with no attempt at coherence or organization. In this way I can sometimes get much closer to what I really am and feel and think. The writings that I have produced on this basis turn out to be ones for which I never feel apologetic and which often communicate deeply to others. So it is a very satisfying thing when I sense that I have gotten close to me, to the feelings and hidden aspects of myself that live below the surface.

I feel a sense of satisfaction when I can dare to communicate the realness in me to another This is far from easy, partly because what I am experiencing keeps changing every moment. Usually there is a lag, sometimes of moments, sometimes of days, weeks, or months, between the experiencing and the communication: I experience something; I feel something, but only later do I dare to communicate it, when it has become cool enough to risk sharing it with another. But when I can communicate what is real in me at the moment that it occurs, I feel genuine, spontaneous, and alive.

It is a sparkling thing when I encounter realness in another person. Sometimes in the basic encounter groups which have been a very important part of my experience these last few years, someone says something that comes from him transparently and whole. It is so obvious when a person is not hiding behind a facade but is speaking from deep within himself. When this happens, I leap to meet it. I want to encounter this real person. Sometimes the feelings thus expressed are very positive feelings; sometimes they are decidedly negative ones. I think of a man in a very responsible position, a scientist at the head of a large research department in a huge electronics firm. One day in such an encounter group he found the courage to speak of his isolation. He told us that he had never had a single friend in his life; there were plenty of people whom he knew but not one he could count as a friend. “As a matter of fact,” he added, “there are only two individuals in the world with whom I have even a reasonably communicative relationship. These are my two children.” By the time he finished, he was letting loose some of the tears of sorrow for himself which I am sure he had held in for many years. But it was the honesty and realness of his loneliness that caused every member of the group to reach out to him in some psychological sense. It was also most significant that his courage in being real enabled all of us to be more genuine in our communications, to come out from behind the facades we ordinarily use.

I regret it when I suppress my feelings too long and they burst forth in ways that are distorted or attacking or hurtful. I have a friend whom I like very much but who has one particular pattern of behavior that thoroughly annoys me. Because of the usual tendency to be nice, polite, and pleasant I kept this annoyance to myself for too long and, when it finally burst its bounds, it came out not only as annoyance but as an attack on him. This was hurtful, and it took us some time to repair the relationship.

I am inwardly pleased when I have the strength to permit another person to be his own realness and to be separate from me. I think that is often a very threatening possibility. In some ways I have found it an ultimate test of staff leadership and of parenthood. Can I freely permit this staff member or my son or my daughter to become a separate person with ideas, purposes, and values which may not be identical with my own? I think of one staff member this past year who showed many flashes of brilliance but who clearly held values different from mine and behaved in ways very different from the ways in which I would behave. It was a real struggle, in which I feel I was only partially successful, to let him be himself, to let him develop as a person entirely separate from me and my ideas and my values. Yet to the extent that I was successful, I was pleased with myself, because I think this permission to be a separate person is what makes for the autonomous development of another individual.

I am angry with myself when I discover that I have been subtly controlling and molding another person in my own image. This has been a very painful part of my professional experience. I hate to have “disciples,” students who have molded themselves meticulously into the pattern that they feel I wish. Some of the responsibility I place with them, but I cannot avoid the uncomfortable probability that in unknown ways I have subtly controlled such individuals and made them into carbon copies of myself, instead of the separate professional persons they have every right to become.

From what I have been saying, I trust it is clear that when I can permit realness in myself or sense it or permit it in another, I am very satisfied. When I cannot permit it in myself or fail to permit it in another, I am very distressed. When I am able to let myself be congruent and genuine, I often help the other person. When the other person is transparently real and congruent, he often helps me. In those rare moments when a deep realness in one meets a realness in the other, a memorable “I-thou relationship,” as Martin Buber would call it, occurs. Such a deep and mutual personal encounter does not happen often, but I am convinced that unless it happens occasionally, we are not living as human beings.

I want to move on to another area of my learning in interpersonal relationships – one that has been slow and painful for me.

I feel warmed and fulfilled when I can let in the fact, or permit myself to feel, that someone cares for, accepts, admires, or prizes me. Because of elements in my past history, I suppose, it has been very difficult for me to do this. For a long time I tended almost automatically to brush aside any positive feelings aimed in my direction. My reaction was, “Who, me? You couldn’t possibly care for me. You might like what I have done, or my achievements, but not me.” This is one respect in which my own therapy helped me very much. I am not always able even now to let in such warm and loving feelings from others, but I find it very releasing when I can do so. I know that some people flatter me in order to gain something for themselves; some people praise me because they are afraid to be hostile. But I have come to recognize the fact that some people genuinely appreciate me, like me, love me, and I want to sense that fact and let it in. I think I have become less aloof as I have been able to take in and soak up those loving feelings.

I feel enriched when I can truly prize or care for or love another person and when I can let that feeling flow out to that person. Like many others, I used to fear being trapped by letting my feelings show. “If I care for him, he can control me.” “If I love her, I am trying to control her.” I think that I have moved a long way toward being less fearful in this respect. Like my clients, I too have slowly learned that tender, positive feelings are not dangerous either to give or to receive.

To illustrate what I mean, I would like again to draw an example from a recent basic encounter group. A woman who described herself as “a loud, prickly, hyperactive individual” whose marriage was on the rocks, and who felt that life was just not worth living, said, “I had really buried under a layer of concrete many feelings I was afraid people were going to laugh at or stomp on which, needless to say, was working all kinds of hell on my family and me. I had been looking forward to the workshop with my last few crumbs of hope – it was really a needle of trust in a huge haystack of despair.” She spoke of some of her experiences in the group and added, “The real turning point for me was a simple gesture on your part of putting your arm around my shoulder, one afternoon when I’d made some crack about you not really being a member of the group – that no one could cry on your shoulder. In my notes I had written, the night before, ‘My God, there’s no man in the world who loves me.’ You seemed so genuinely concerned the day I fell apart, I was overwhelmed. . . . I received the gesture as one of the first feelings of acceptance – of me, just the dumb way I am, prickles and all – that I had ever experienced. I have felt needed, loving, competent, furious, frantic, anything and everything but just plain loved. You can imagine the flood of gratitude, humility, almost release, that swept over me. I wrote, with considerable joy, ‘I actually felt love.’ I doubt that I shall soon forget it.”

This woman, of course, was speaking to me, and yet in some deep sense she was also speaking for me. I too have had similar feelings.

Another example concerns the experiencing and giving of love. I think of one governmental executive in a group in which I participated, a man with high responsibility and excellent technical training as an engineer. At the first meeting of the group he impressed me, and I think others, as being cold, aloof, somewhat bitter, resentful, and cynical. When he spoke of how he ran his office, it appeared that he administered it “by the book,” without any warmth or human feeling. In one of the early sessions he was speaking of his wife, and a group member asked him, “Do you love your wife?” He paused for a lorg time and the questioner said, “O.K. That’s answer enough.” The executive said, “No. Wait a minute. The reason I didn’t respond was that I was wondering, ‘Have I ever loved anyone?’ I don’t really think I have ever loved anyone.”

A few days later, he listened with great intensity as one member of the group revealed many personal feelings of isolation and loneliness and spoke of the extent to which he had been living behind a facade. The next morning the engineer said, “Last night I thought and thought about what he told us. I even wept quite a bit myself. I can’t remember how long it has been since I have cried, and I really felt something. I think perhaps what I felt was love.”

It is not surprising that before the week was over, he had thought through different ways of handling his growing son, on whom he had been placing very rigorous demands. He had also begun to really appreciate the love his wife had extended to him – love that he now felt he could in some measure reciprocate.

Because of having less fear of giving or receiving positive feelings, I have become more able to appreciate individuals. I have come to believe that this ability is rather rare; so often, even with our children, we love them to control them rather than loving them because we appreciate them. One of the most satisfying feelings I know – and also one of the most growth-promoting experiences for the other person – comes from my appreciating this individual in the same way that I appreciate a sunset. People are just as wonderful as sunsets if I can let them be. In fact, perhaps the reason we can truly appreciate a sunset is that we cannot control it. When I look at a sunset as I did the other evening, I don’t find myself saying, “Soften the orange a little on the right hand corner, and put a bit more purple along the base, and use a little more pink in the cloud color.” I don’t do that. I don’t try to control a sunset. I watch it with awe as it unfolds. I like myself best when I can appreciate my staff member, my son, my daughter, my grandchildren, in this same way. I believe this is a somewhat Oriental attitude; for me it is a most satisfying one.

Another learning I would like to mention briefly is one of which I am not proud but which seems to be a fact. When I am not prized and appreciated, I not only feel very much diminished, but my behavior is actually affected by my feelings. When I am prized, I blossom and expand, I am an interesting individual. In a hostile or unappreciative group, I am just not much of anything. People wonder, with very good reason, how did he ever get a reputation? I wish I had the strength to be more similar in both kinds of groups, but actually the person I am in a warm and interested group is different from the person I am in a hostile or cold group.

Thus, prizing or loving and being prized or loved is experienced as very growth enhancing. A person who is loved appreciatively, not possessively, blooms and develops his own unique self. The person who loves nonpossessively is himself enriched. This, at least, has been my experience.

I could give you some of the research evidence which shows that these qualities I have mentioned – an ability to listen empathically, a congruence or genuineness, an acceptance or prizing of the other – when they are present in a relationship make for good communication, and for constructive change in personality. But I feel that, somehow, research evidence is out of place in a talk such as I have been giving.

I want to close instead with two statements drawn again from an intensive group experience. This was a one-week workshop, and the two statements I am quoting were written a number of weeks later by two members of the workshop. We had asked each individual to write about his current feelings and to address this to all the members of the group.

The first statement is written by a man who tells of the fact that he had some rather difficult experiences immediately after the workshop, including spending time with:

a father-in-law who doesn’t care much about me as a person but only in what I concretely accomplish. I was severely shaken. It was like going from one extreme to another. I again began to doubt my purpose and particularly my usefulness. But time and again I would hearken back to the group, to things you’ve said or done that gave me a feeling that I do have something to offer – that I don’t have to demonstrate concretely to be worthwhile – and this would even the scale and lift me out of my depression. I have come to the conclusion that my experiences with you have profoundly affected me, and I am truly grateful. This is different from personal therapy. None of you had to care about me, none of you needed to seek me out and let me know of things you thought would help me, none of you had to let me know that I was of help to you – yet you did, and as a result, it has far more meaning than anything I have so far experienced. When I feel the need to hold back and not live spontaneously, for whatever reason, I remember that twelve persons, just like these before me, said to let go and be congruent, to be myself, and of all unbelievable things, they even loved me more for it. This has given me the courage to come out of myself many times since then. Often it seems, my very doing of this helps the others to experience similar freedom.

I have also been able to let others into my life more – to let them care for me and to receive their warmth. I remember the time in our group encounter when this change occurred. It felt like I had removed long-standing barriers – so much so that I deeply felt a new experience of openness toward you. I didn’t have to be afraid, I didn’t have to fight or fearfully pull away from the freedom this offered my own impulses – I could just be and let you be with me.

The second excerpt is taken from the report of a woman who had come with her husband to this workshop in human relations, although she and her husband were in separate groups. She talks at some length about her experience in revealing her feelings to the group and the results of taking that step.

Taking the plunge was one of the hardest things I have ever done. I have hidden my feelings of hurt and loneliness from even my closest friends while I was feeling them. Only when I had suppressed my feelings and could speak jokingly or casually could I share painful things at all, but that didn’t help me work through them. You knocked down the walls that were holding back hurt, and it was good to be with you and hurt – and not withdraw.

Also, before, it had been so painful to me to be misunderstood or criticized that I chose not to share truly meaningful events, good or bad, most of my life. Only recently have I dared risk the hurt. In the group I faced these fears and was relieved beyond measure to find that my feelings in response to your criticism and misunderstanding (so blessedly devoid of hostility, I felt) were not deep hurt, but more curiosity, regret, irritation, perhaps sadness, and [I felt] a deep sense of gratitude for the help I experienced in looking at part of me I had not seen nor wanted to face before. I am sure my perception of your concern and respect for the person, even when my behavior might irritate or alienate you, makes it possible for me to accept all of this and find it helpful.

There were times I felt very afraid of the group, though never of you individually. I needed very much at times to talk with just an individual, but during the course of the week discovered that most of you at some time or other were a real help to me. What a release to find so many instead of just the leaders. This experience opened me to a deeper trust in people, increased my ability to be open with others.

One of the nicest results is that now I can completely relax. I didn’t realize how much constant tension I was under until I suddenly wasn’t! I am now much more sensitive to the times when my emotions or fatigue make me a poor listener, for I find that my own inner hurts and anxiety, even suppressed, interfered with my really listening to another. Since then I have been able to listen better and to respond more helpfully than ever before in my life. I have been far more aware of what I was feeling and experiencing myself an openness to myself I never had before.

Congruence was more an ideal than reality to me. Frankly, I found it disconcerting to experience and frightening to express. This was the first really safe place I had found to see what I was like, to experience and express myself. I now find that a lack of congruence in myself is painful. The release and joy in my being open to what I was experiencing within and being able to keep this openness between us was new and uplifting. I am deeply grateful to you who have made it possible for us to be so much more open with each other.

I trust that you will see in these experiences some of the elements of growth-promoting interpersonal communication that have had meaning for me. A sensitive ability to hear, a deep satisfaction in being heard; an ability to be more real, which in turn brings forth more realness from others; and consequently a greater freedom to give and receive love – these, in my experience, are the elements that make interpersonal communication enriching and enhancing.