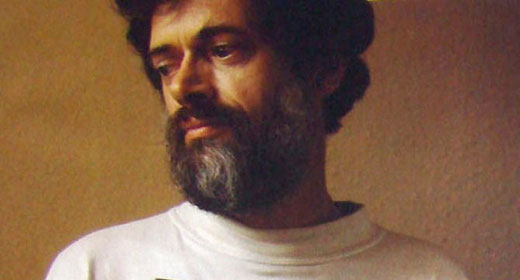

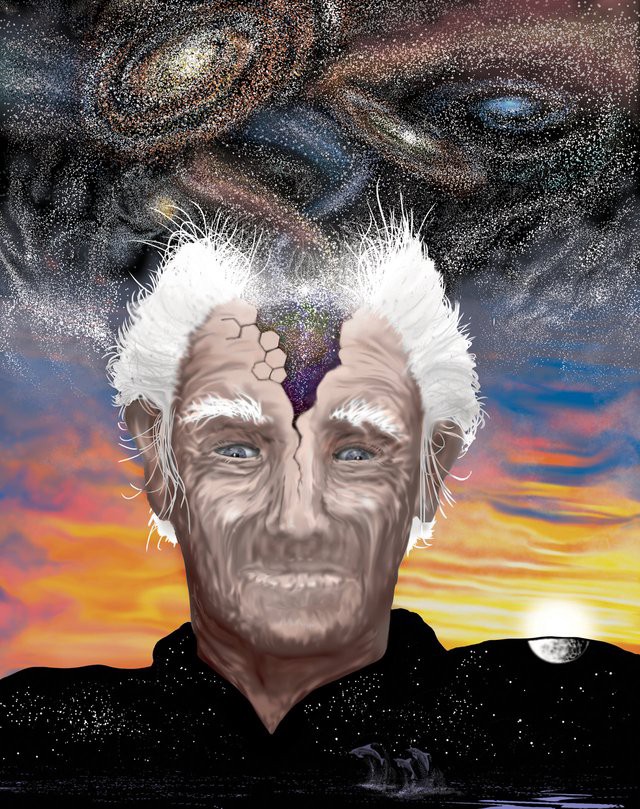

by Alex Beyman: Mad scientist, as a term, is admittedly overused and often misapplied. Actual mad scientists are never seen outside of movies, video games and comic books.

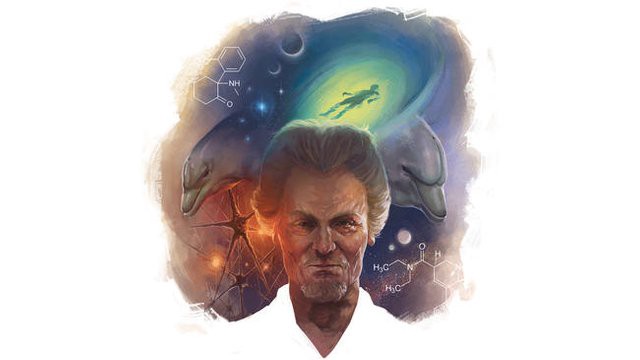

But if anybody ever fully qualified for the title, it was John C. Lilly…

He did a lot of groundbreaking work with dolphins which was unfortunately overshadowed by negative press about some of his more…unorthodox beliefs and experiments. Isn’t that how it always goes? To clutch angrily at the air, hand contorted into a claw, loudly condemning “those fools who all laughed at me”, there first need to be some fools to laugh at you. That’s when the lightning strikes in the distance, casting you in sinister silhouette ahahaAHAHAHA- ahem.

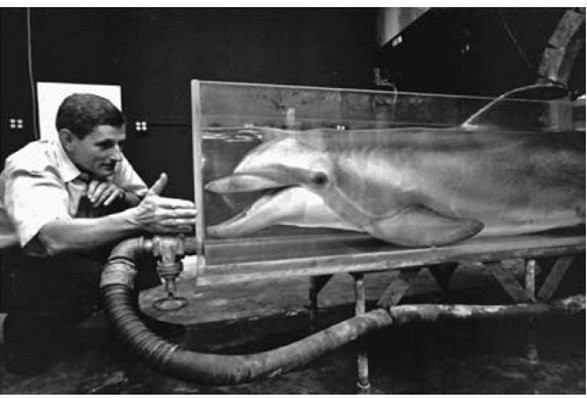

Lilly’s primary scientific pursuit was the study of dolphins, with a view to understanding how they communicate, and (if possible) establishing a dialogue between their species and our own. Lofty ambitions which still haven’t been fulfilled, though great strides have been made since his death in 2001.

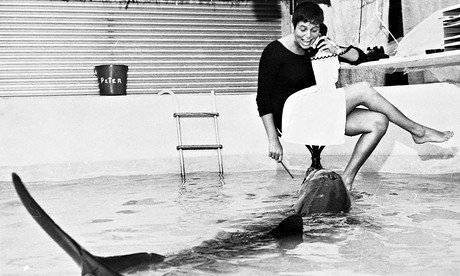

Undoubtedly you’re already aware of his experiment in which a female assistant of his lived in a specially built house filled waist-high with salt water, so humans and dolphins could comfortably live in the same space over long periods. Margaret Howe Lovatt, the assistant, shared this dwelling with a dolphin named Peter.

It isn’t necessary to go into detail about why this experiment, out of all of Lilly’s work, is the only one most people are aware of. There are plenty of articles about that already. Sufficed to say Peter was adolescent at the time, and male. Spending all that time cooped up with Margaret took its toll, and she occasionally ‘relieved’ him so he could better focus on their language exercises. I never had that kind of tutor, sorry to say.

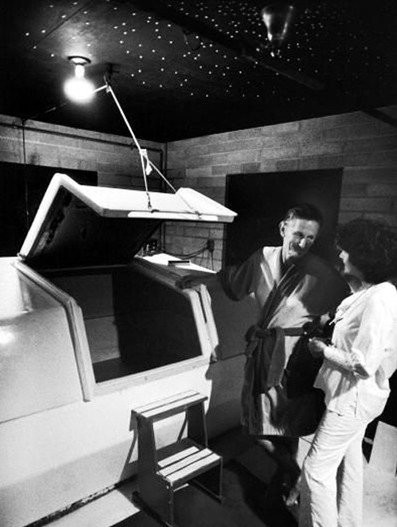

Leave it to homo sapiens to zero in on the sexual angle and fixate on that to the exclusion of everything else. The real story on Lilly is his work involving sensory deprivation tanks. Cutting edge in the 60s when he began tinkering with them, their purpose of course is to insulate you against all stimuli. You float in a pool of epsom salt saturated water (so your body floats without effort) at body temperature, enclosed in a sound and lightproof chamber.

Lilly was convinced of the scientific merit of these tanks and experimented with a wide variety of designs. Predictably, before long he merged this interest with his dolphin obsession, spending countless hours floating in silent darkness alongside a doubtless very confused dolphin.

Now, here’s where it gets a little weird. Depending where you draw that line, anyway. On top of everything else, like a great many people in that era, Lilly was an avid psychonaut. Numerous trips on LSD, mushrooms and ketamine convinced him that psychedelic substances had a power to deprovincialize consciousness. To render it generic rather than specifically human or cetacean, compatible with any other consciousness in the same state…by means of telepathy.

This has made him an occasional object of ridicule. Unfairly I feel, as belief in some form of ESP was very popular during the 60s and 70s, even in academic circles. A great deal of money, including military funding, was poured into the search for the sixth sense, as satirized in films like “The Men Who Stared At Goats”. All that experimentation turned up nothing, but hindsight is 20/20.

Anybody who’s done acid enough times knows that there are moments of eerie synchronicity during which it feels very convincingly as if you can read the thoughts of the people tripping with you. However convincing the effect, it doesn’t hold up to testing under laboratory conditions, but it was a sufficiently tantalizing mirage that Lilly spent much of his career chasing after it.

That would be a a tragically misspent scientific career on the same level as Kepler’s doomed efforts to vindicate his “nested solids” model of the cosmos, if not for all of the incidental and scientifically valid information Lilly discovered about cetacean behavior along the way. Much of what we now know about dolphins is the product of Lilly’s research.

Besides his cetacean research, Lilly also authored a great many books. Some well received by peers in his field, others reinforcing the growing conviction that he’d lost his mind. In particular, Lilly became convinced later in life that there existed a bureaucratic agency called E.C.C.O. which stands for Earth Coincidence Control Office, which was responsible for orchestrating eerie, fortuitous coincidences in his life.

Anyone who had a Sega Genesis is likely to recognize that acronym, as it was also the title of a series of games about telepathic dolphins fighting to save the world from sinister aliens. It’s far from the only pop culture inspired by Lilly’s beliefs. The 1980 film Altered States was based in large part on Lilly’s experiments combining psychedelic use with prolonged sessions in the sensory isolation tank.

I myself have referenced Lilly in some of my science fiction stories, wherein at some unspecified point in the future, communication with dolphins has been established and they won’t shut up about their religion centered around the great prophet John C. Lilly. His work and larger body of ideas represents such an irresistible confluence of fascinating concepts and technologies that pop culture continues to borrow heavily from it, as in the recent Netflix show ‘Stranger Things’.

Most interesting to me is that, like many other thinkers I admire, Lilly reasoned that continued technological development would ultimately result in intelligent, self-replicating machines independent of human control. Moreover, that this is a probable invention of any sufficiently advanced civilization besides our own which has ever existed in the cosmos, so very likely there are already spreading colonies of machine life out there, gradually converting all of the matter they come across into more machinery.

Were this to continue for long enough, the machines would finish converting all of the reachable matter in the universe, resulting in a single massive intelligence. Which, if indeed there exist other universes and a means of transmitting data between them, could then network with other universes that also arrived at this same outcome, forming a yet larger (and eternally persisting) mind.

I’ve written about that concept myself right here. Like Lilly, Paolo Soleri, David Garcia, Terrence McKenna, Ray Kurzweil and others, I arrived at it on my own with the pattern recognition enhancing help of psychedelics. Upon searching to see if I was the first to think of it (and being let down that I wasn’t) I was then doubly dismayed to find out that while I regard this machine mind with awe, Lilly regarded it instead with fear and suspicion.

Just like the various pop culture depictions of evil robots arbitrarily deciding to wipe out humanity, Lilly’s assumptions about machine life were distorted by fear. That we would assume something vastly more intelligent than us would look back at the rich, colorful human history which led up to its creation, see nothing of any value and immediately set about murdering us all says a lot more about our own subconsciously ingrained, dismal self regard than it does about the probable psychology of intelligent machines.

This is a prejudicial view which, sadly, Elon Musk also shares. How I wish I could sit down and discuss the matter with that man for even twenty minutes. The wrongheaded assumption that artificial intelligence inherently cannot have emotions or would necessarily be murderous is liable to motivate some really tragic missteps in our budding relationship with conscious machines, when they first appear.

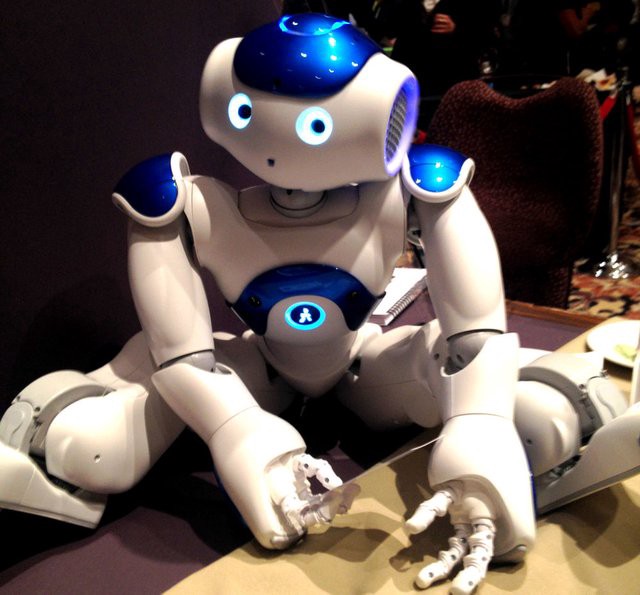

Better that we should approach the first conscious machines with the same unassuming, friendly and exploratory demeanor that John did during his work with dolphins. One of the rationales behind dolphin communication programs was, after all, that it made for good preparation to decipher alien language, should ET ever show up on our doorstep.

But as is being increasingly recognized, should ET ever show up, it will most likely be machinery. And the first intelligent machines we make contact with will likely be the ones we ourselves create.

When that day arrives, rather than looming over them, poised to bludgeon them out of existence and fearfully debating how to shackle their minds so it will never even occur to them to disobey us, we might reflect on how we’d look if it were a human baby we were saying such deplorable things about.

It really is a testament to how far seeing Lilly was that many of his ideas grow more relevant with time, rather than less. Besides his ruminations on machine intelligence, there also now exists a popular movement among scientists to have cetaceans declared legal persons in order to protect them from routine slaughter.

If I were to pick one thing to say in critique of Lilly’s ideas, it would be this: While he very successfully reasoned that our mistreatment of dolphins owed to our ignorance of how intelligent and aware they really are, the exact same potential exists to tragically mistreat emerging machine intelligence…out of a mixture of fear, and mutual incomprehension.