by Ocean Robbins: We’ve known about the vitamin antioxidants for a long time: vitamin C, vitamin E, and beta-carotene leap to mind.

We are proud to announce a new partnership with John and Ocean Robbins and the Food Revolution to bring our readers Summits, Seminars and Masterclasses on health, nutrition and Earth-Conscious living.

Sign Up Today For the Food Revolution Summit Docuseries

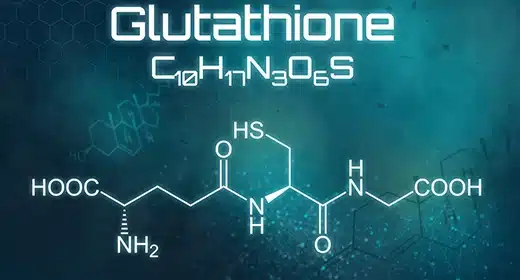

Recently, other phytonutrients such as lycopene and resveratrol have been having their day in the sun. But there’s one antioxidant that may be the most important of all, and it hasn’t really received the amount of attention justified by its impressive benefits. In this article, let’s get to know the dietary antioxidant glutathione.

Due to an extreme shortage of auto parts in the Soviet era, Russians often couldn’t just get a new pair of windshield wipers at the store when the old ones wore out. It was common for someone to return to their car to discover that someone had nicked their wipers. The afflicted party might then grab a pair from a nearby car to replace their own. And so on, until large segments of the motoring population became engaged in a never-ending game of musical chairs (or rather wipers), grabbing them wherever they could.

This chain reaction became so widespread during the Soviet Union that almost no parked cars had visible windshield wipers. Instead, drivers would remove them with a screwdriver, and only put them back in case of heavy rain.

Bear with me, but there’s something similar going on in your body all the time: a process known as lipid peroxidation. Basically, the thief here is a free radical, and the stolen object is an electron taken from a lipid molecule in the membrane of a cell. That lipid molecule then becomes unstable, and in turn, grabs an electron from a neighboring cell, and so on and so on.

This process can really damage your health, affecting most chronic diseases, including type 2 diabetes, Alzheimer’s, atherosclerotic plaque (which itself can lead to heart disease and stroke), and cancer.

Fortunately, your body also contains crime-fighting compounds called antioxidants that fight free radicals and protect against oxidative damage. And one of the most powerful and ubiquitous antioxidants is glutathione.

First discovered in 1888 by J. de Rey-Paihade, a French doctor, glutathione was found in high concentrations in most of the cells of the human body, especially in the liver. These days, many health influencers talk about its benefits for a number of conditions, and also tout its potential to slow the aging process.

But what exactly is glutathione? What claims for its benefits are valid, and what’s currently just speculation or hype? How do you make sure you have enough in your body? And can you make it all yourself, do you need to get it from food, or do you need to supplement?

What Is Glutathione?

First things first: pronunciation. Since you’ll be saying “glutathione” to yourself a lot as you read this article, you might want to make sure you’re saying it right. The word is pronounced “gloo-tuh-thigh-own.” Or, for an image you might not be able to get out of your head, just picture gluing tuh’ your own thigh. (Or not. There’s a reason I’m not a linguistics professor.)

Glutathione is one of the most potent antioxidants in the body. It binds to fat-soluble toxins — the electron thieves that we just met — as well as heavy metals that make their way into the body. As such, it supports the liver and kidneys as they work to detoxify harmful compounds, both organic and inorganic. Glutathione also helps make proteins in the body and regulates the function of the immune system.

Your body naturally produces glutathione in your cells. The largest producer is the liver, which creates it from three amino acids: cysteine, glutamate, and glycine. That’s why glutathione is characterized as a tripeptide (“three peptides”).

Since glutathione serves to fight the free radicals that cause oxidative damage, we want our bodies to increase the concentration of glutathione in cells in response to oxidation. And one of the safest and most effective ways to raise resting levels of glutathione appears to be exercise. Just as lifting weights can grow your muscles and cardio can strengthen your heart, temporarily raising free radical levels through physical activity creates adaptations that increase glutathione activity throughout the body.

Benefits of Glutathione

Due to its key roles in detoxification, fighting free radicals, and making essential proteins, glutathione is indispensable for health. Low levels of glutathione are associated with a number of diseases and conditions. In some cases, clinical trials have revealed a causal relationship (that is, raising glutathione levels makes things better). And in others, it’s still unclear if low glutathione is a cause of a symptom, or if the condition itself has suppressed glutathione synthesis.

Glutathione and the Liver

Since the liver is ground zero for glutathione production, it makes sense that glutathione levels are lower in people with a variety of liver disorders and diseases.

Medical research has found that glutathione supplementation can help mitigate the effects of liver disease. A small 2017 clinical trial found that people with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) had their liver function improve when given supplemental glutathione. This is good news, as NAFLD is associated with the development of insulin resistance (a root cause of type 2 diabetes), obesity, and high blood pressure.

Glutathione also appears to restore some liver function in those with alcoholic liver disease.

Glutathione and the Immune System

When your glutathione stores are low, your body is less able to fight off viral infections. And glutathione also participates in the development of trained immunity, whereby your immune system gets better at defeating pathogens through exposure. A 2021 study showed that high concentrations of glutathione in plasma cells were associated with some immune cells’ ability to “remember” past infections and deal with new ones more effectively.

One way glutathione supports the immune system is by inducing a phenomenon called macrophage polarization, in which macrophages (the immune cells that gobble up pathogens; their name is Greek for “big eaters”) can adjust their programming based on environmental signals. A 2022 microbiology paper argued that glutathione deficiency could even be a risk factor in life-threatening cases of COVID-19.

Glutathione and the Brain

One of glutathione’s impressive list of feats is its ability to regulate brain metabolism. It turns out that when glutathione function is impaired, the brain loses more neurons — a process that’s associated with cognitive decline, Alzheimer’s, and increased risk of depression and anxiety. It’s also clear that insufficient glutathione may contribute to Parkinson’s disease.

One of the challenges in glutathione research is knowing how to measure it accurately. Researchers are still debating the best way to determine brain concentrations of glutathione. Doing so is important because there’s evidence that too little and too much glutathione may contribute to mood disorders like depression and schizophrenia.

Glutathione and Cancer

As one of the “master conductors” of cellular behavior, glutathione can tell cells to do a bunch of different things, including divide, grow, protect themselves, and self-destruct. All these processes are involved in cancer. And glutathione appears to be a double-edged sword in this case. It can tell damaged cells to die, either through apoptosis (programmed cell death) or a recently discovered type of cell death called ferroptosis, which relies on iron and reactive oxygen species (ROS) to basically blow up a cell’s mitochondria from the inside.

But glutathione can also become a cheerleader for cancer; elevated levels in tumor cells can trigger the progression of tumors and increase resistance to anticancer drugs. It appears to be a matter of timing: Glutathione removes and detoxifies carcinogens, which prevents the initiation of cancer, but it also promotes the growth and metastasis of already-formed tumors.

It appears that glutathione isn’t a “more is always better” molecule when it comes to cancer. Good health depends on a homeostatic balance between oxidation and its chemical opposite, reduction. Too much glutathione appears to tilt the balance, and not necessarily in the right direction. So rather than simply giving someone a glutathione supplement, novel cancer treatments are looking at closely modulating glutathione levels and strategically “interfering” with different steps in the glutathione metabolic cycle to improve existing cancer therapies.

Glutathione and Type 2 Diabetes

There’s definitely a link between glutathione deficiency and the presence of type 2 diabetes. But it’s not entirely clear yet which one causes the other (or whether both are caused by an as-yet-unknown initial factor).

A 2018 study of just 24 people (16 with type 2 diabetes and 8 matched controls who did not have the disease) found that the people with type 2 diabetes had lower glutathione concentrations, suggesting that something about the disease might cause less tripeptide production. Additionally, it appears that there’s something about excess blood sugar that requires more glutathione, leaving less for other critical functions.

For someone with type 2 diabetes, the question of causality may be less important than finding out if glutathione supplementation can improve symptoms and mitigate progression.

A 2021 controlled trial out of Denmark sought to answer that question, studying the effects of three weeks of oral glutathione supplementation in 20 obese males — 10 with type 2 diabetes, and 10 without. The 20 were randomized to receive either 1,000 mg GSH (a common form of glutathione present in the body) or a placebo.

The results were promising: the group receiving glutathione improved their whole-body insulin sensitivity, meaning that it became easier for them to move glucose from the bloodstream into the cells. And the glutathione had apparently been absorbed and sent to where it was needed; a muscle biopsy confirmed that GSH concentrations increased by 19% in skeletal muscles. These findings occurred in subjects both with and without type 2 diabetes, suggesting that oral glutathione could help prevent prediabetes from developing into full-blown diabetes.

Ways to Boost Glutathione Levels

For most people, the best way to boost glutathione levels is to eat foods that contain glutathione or its precursors. (More on that coming soon.) A few of the nutrients that appear especially important to helping your body make and synthesize it effectively include:

Vitamin C: A group of researchers discovered that consumption of vitamin C supplements resulted in a rise in glutathione levels in the white blood cells of healthy adults. One particular study found that consuming 500mg of vitamin C daily led to a 47% hike in glutathione levels in red blood cells.

Selenium: One investigation analyzed the impact of selenium supplementation on 45 adults suffering from chronic kidney disease. The participants got a daily dose of 200mcg of selenium for a period of three months. The results revealed a significant increase in the levels of glutathione peroxidase in all of the participants. Another study demonstrated that the consumption of selenium supplements led to an elevation in glutathione peroxidase levels among patients undergoing hemodialysis. Perhaps the best way to ensure an adequate supply of selenium is to eat 1–2 Brazil nuts per day.

Turmeric: Turmeric is a brightly colored herb with vast therapeutic and anti-inflammatory properties. Several animal and laboratory studies have demonstrated that turmeric and its extract, curcumin, have the potential to raise glutathione levels. Researchers believe that the curcumin found in turmeric can enhance the functioning of glutathione enzymes.

Food Sources of Glutathione

Some nutrients are essential, meaning that your body can’t manufacture them and you have to get them from food (vitamin C, for example). But glutathione isn’t like that; you can manufacture it in your liver and increase its production by creating appropriate amounts of oxidative stress through exercise.

But that doesn’t mean nutrition isn’t important here. You still need to consume the building blocks of glutathione. And many plant foods provide those building blocks, either in the form of amino acids, precursor molecules, or in some cases, glutathione itself. The following are some of the best food sources of glutathione and glutathione precursors.

1. Alliums

Onions and garlic were both found to increase concentrations of a few forms of glutathione in rats. Both alliums raised GSH levels in the animals’ livers and kidneys. This may be one of the many mechanisms by which onions and garlic can prevent cancer.

Check out our full article on alliums for much more good news about onions and garlic.

2. Avocados

Avocados contain glutathione, along with many other health-promoting compounds. A 2021 animal study compared avocado oil to a common hypertensive drug, prazosin, and found that, while both treatments decreased high blood pressure in hypertensive rats, only the avocado oil improved the mitochondrial function in the rats’ kidney cells. The avocado oil, the researchers found, improved the ability of glutathione to neutralize free radicals and thereby prevent the damage often caused by high blood pressure.

Read all about the health benefits of avocados (with recipes) in our comprehensive article.

3. Asparagus

If you’ve ever eaten asparagus and then noticed a funny smell when you urinate, the culprits are sulfur-containing compounds that form when asparagusic acid breaks down. Sulfur is one of the main ingredients in glutamate, which as you may recall is one of the three amino acids that form glutathione. Sulfur is also critical for the synthesis of glutathione. For the highest concentrations of these beneficial compounds, choose brightly colored green asparagus spears rather than pale or white ones.

Other plant-based foods that are high in sulfur, and that are associated with increased glutathione levels, include cruciferous vegetables like cauliflower, broccoli, broccoli sprouts, kale, brussels sprouts, and mustard greens.

We don’t yet have a comprehensive article on asparagus, but until we write it, you can enjoy this Creamy Asparagus Risotto recipe.

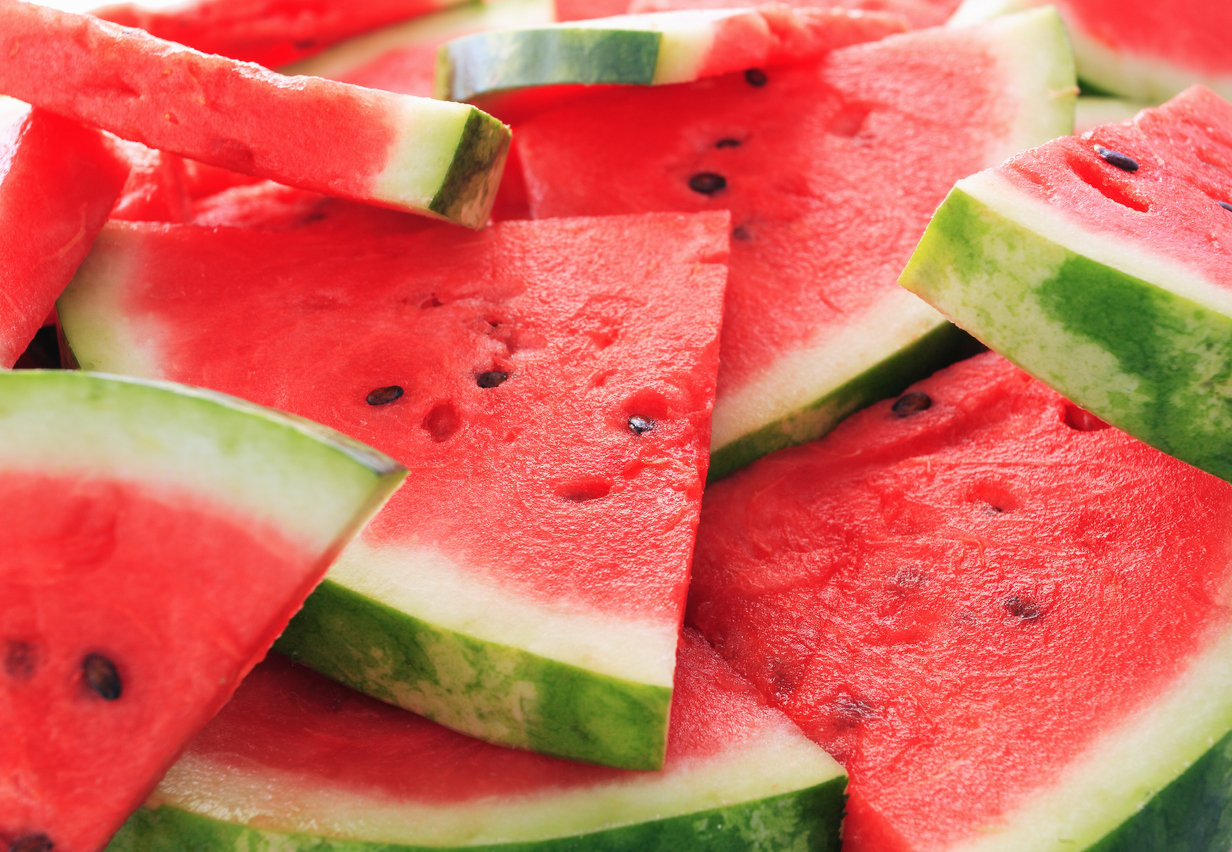

4. Watermelon

Watermelon is rich in many compounds, among them lycopene and vitamin C. Both of these may lower biomarkers of oxidative stress and inflammation, partially through increased glutathione production.

5. Pomegranate

Pomegranates are another red fruit that can boost glutathione levels. A 2014 study fed pomegranate juice to 14 healthy volunteers for 15 days and found that their GSH levels had risen by almost 23% by the last day of the trial. And a 2017 study gave pomegranate juice or a placebo to 9 elite weightlifters right after a strenuous workout. Among many other positive effects, the pomegranate juice increased the antioxidant power of glutathione by about 7%.

6. Mushrooms

Some mushroom species are high in glutathione itself. One of them, Agaricus bisporus, may sound exotic — but fortunately, that’s just the fancy botanical term for the common white button mushroom! A long-term study of over 15,000 participants found that the more mushrooms people reported eating, the lower their chances of dying. So whether it’s the glutathione or the full symphony of nutrients found in edible fungi, mushrooms can be a great addition to most diets.

Glutathione Deficiency

Because glutathione is so important across so many systems and functions, if you’re in good health, you’re probably not deficient. But it is possible to develop a deficiency, due to either aging, certain medical conditions, or a combination of the two.

You can test for glutathione levels via a blood test. Optimal glutathione levels are between 177 and 323 μg/ml (which you say as “micrograms per milliliter”).

The tests can measure glutathione levels in both red blood cells and plasma. And another biomarker for glutathione levels is an enzyme called gamma glutamyltransferase, or GGT. When it’s high, glutathione is often low.

If you need to check your numbers, talk with your health care provider about which measure is more appropriate for you.

Do Glutathione Supplements Work?

Some studies show that supplementing with oral glutathione is effective for deficiency, while others show glutathione is poorly absorbed orally. While it may depend on the person and the condition, there’s some recent research suggesting that two forms of oral glutathione might be more bioavailable and therefore more effective in raising systemic glutathione levels.

The two forms of glutathione supplements that show the most promise are liposomal and sublingual.Liposomal glutathione supplements are prepackaged in a packet of fat cells, made to mimic the structure of our own cells. This can protect the glutathione from being broken down by digestive enzymes during the digestive process. Sublingual (under the tongue) glutathione gets absorbed into the mucous membranes of the mouth, which also increases transit time and bioavailability.

Another option is intravenous glutathione supplementation, which may also be more effective in raising blood levels than oral intake. (That kind of makes sense, since you might imagine that when you inject something into your blood, doing so would increase your blood levels of it.)

A different supplement, N-acetylcysteine (NAC), is currently being studied as a supplement for glutathione support. Again, the research is not conclusive — results differ from disease to disease. But it appears people who supplement with NAC in conjunction with cysteine and glycine may experience a boost in glutathione levels, especially among those who may not have adequate quantities of the amino acids or who need higher levels of glutathione.

Who May Want to Supplement With Glutathione?

As we’ve seen, glutathione does a lot of things. Two of its most urgent and therefore prioritized jobs are dealing with oxidative stress — basically, protecting cells from ROS and other free radicals — and detoxifying heavy metals and other contaminants. When that job becomes overwhelming, your body may not be able to produce enough glutathione to take care of other, less immediate concerns.

So if someone is dealing with lots of stress, which can also include malnutrition or exposure to environmental contaminants, they may need to supplement with glutathione just to keep up with demand.

For example, smokers and those with alcohol abuse problems tend to have decreased glutathione levels and may benefit from supplementation. And people with AIDS or cystic fibrosis may benefit from (or may need to take) glutathione supplements as well.

The elderly may also experience decreased glutathione levels as their natural supplies of the amino acids glycine and cysteine diminish.

And there’s some research showing that glutathione supplementation may aid in recovery from extended aerobic exercise, and so may become a helpful part of the regimen for endurance athletes.

A word of caution: for cancer patients undergoing chemotherapy, it’s important not to get too much, as glutathione can increase their resistance to chemo drugs.

How Much Glutathione Should You Take?

The recommended dose for adults who are choosing to supplement is generally going to be 500–1,000 mg/day of liposomal glutathione.

For glycine, the standard dosage is 3 grams per day, and it’s considered safe up to 6 grams. And for NAC, a standard dose is 600–1,200 mg (that is, 0.6–1.2 grams). And it’s safe up to 3 grams, while 7 grams or more may be toxic.

Recipes with Glutathione-Rich Foods

As we have learned, glutathione is a powerful antioxidant that’s essential for our overall health. While for some people supplementation may be beneficial, these scrumptious recipes are a whole foods way to support your natural production of glutathione. Whether you try these recipes as is, or swap out a few ingredients with others on our glutathione-rich foods list, these antioxidant-rich combinations will not disappoint.

1. Breakfast Chanterelle Avocado Toast

We couldn’t think of a tastier way to support your glutathione needs than with this delicious Breakfast Chanterelle Avocado Toast! Mushrooms are a great source of dietary glutathione, coupled with other nutrients like vitamin D, B vitamins, and fiber. This yummy toast gives you plenty of plant power to keep your glutathione levels healthy.

2. Nutty and Seedy Kale Salad with Pomegranate Vinaigrette

With so many flavorful and nutrient-rich ingredients, it’s no surprise this delicious Nutty and Seedy Kale Salad with Pomegranate Vinaigrette made it to our glutathione-supportive recipes list. Pomegranate and kale offer plenty of antioxidant plant power. Loaded with vitamin C, glucosinolates, and isothiocyanates, this superfood combo increases the antioxidant power of glutathione naturally, making it a great go-to recipe to support your natural glutathione production!

3. Air Fryer Chickpea Cauliflower Tacos

Crunchy air fryer tacos that can help support your immunity and improve your glutathione capacity? Sign us up! Enjoy these savory, crispy, and absolutely delicious cauliflower tacos at your next Taco Tuesday gathering (or any time of the week!), and feel the joy that comes with tasty plant-based antioxidant-rich meals. Cauliflower, kale, silky avocado cream, and green onions help to give a natural boost to your own glutathione production, making it a tasty weeknight meal your whole family will love.

Get to Know Glutathione!

Glutathione is a potent antioxidant that is vital for cellular function and immunity, among many other benefits. It protects against free radicals and oxidative stress that is responsible for a number of chronic diseases, especially those often associated with aging. For most healthy people, supplementation isn’t necessary, as our bodies can make glutathione naturally or source it from the foods we eat. But age, fitness level, and certain medical conditions may warrant supplementation, especially if a deficiency is present. You may want to consult with your healthcare provider about getting your levels checked – and if they’re low, then it’s possible you could benefit from a glutathione supplement.

Is Acrylamide Dangerous & How Can You Avoid it in Your Food?

by Ocean Robbins: Acrylamide sure doesn’t sound like something edible.

We are proud to announce a new partnership with John and Ocean Robbins and the Food Revolution to bring our readers Summits, Seminars and Masterclasses on health, nutrition and Earth-Conscious living.

Sign Up Today For the Food Revolution Summit Docuseries

But nevertheless, the compound is in many of the most popular foods, including baked goods, fried and roasted potatoes, and even coffee. Some evidence suggests that acrylamide can trigger cancer growth — at least in rodents. But is there a cancer risk to humans? And should we try to completely eliminate acrylamide from our diets, or are there ways to cut back on exposure that reduce any potential health effects?

Few foods generate as much controversy as the humble potato. Since its domestication around eight millennia ago in the Andean highlands of what is now Peru, this calorie-rich tuber has played a part in some of the most significant currents of human history. Its introduction to Europe in the 16th century helped save millions from recurrent famines that had plagued the northern part of that continent. It’s also said to have fueled European expansion, domination, and colonization around the globe.

These days, potato skirmishes mostly revolve around nutritional issues. Keto enthusiasts warn against its high carbohydrate content, while starch-loving vegans celebrate that same quality.

But one of the latest potato kerfuffles (no, that’s not a potato chip brand) relates to what happens when you cook potatoes at high temperatures, typically in oil, and form the brown, crispy, crunchy texture that has made foods like chips and french fries some of the world’s most craved foods. While unquestionably adding to the potato’s mouth appeal, the chemical reaction behind this phenomenon produces a compound that may be carcinogenic: acrylamide.

But potatoes aren’t the only food where this chemical reaction may occur. Acrylamide forms in many other foods, including coffee, toast, and even prunes (is nothing sacred?). Perhaps unsurprisingly, our principal dietary source of acrylamide is fast and processed foods, particularly those made from potatoes.

That’s unfortunate, given that for some people, potatoes are one of the only vegetables that routinely passes through their lips.

But can we still have our tubers, or is the amount of acrylamide in them a serious source of danger? And what about other acrylamide-containing foods? Should we avoid coffee, prunes, and toast, or is the threat from this scary-sounding compound overblown?

In this article, we’ll explore the truth about acrylamide: if it really does cause cancer in humans, what foods contain it, and whether it’s something you actually need to worry about.

What Is Acrylamide?

Acrylamide is a chemical compound that forms at very high temperatures, usually as a result of a manufacturing process. Most of the acrylamide in our environment originates in manufacturing and water treatment, but it’s also present in cigarette smoke and some foods.

Your personal exposure to acrylamide is probably limited to secondhand smoke and the food you eat — unless you encounter it as an occupational hazard.

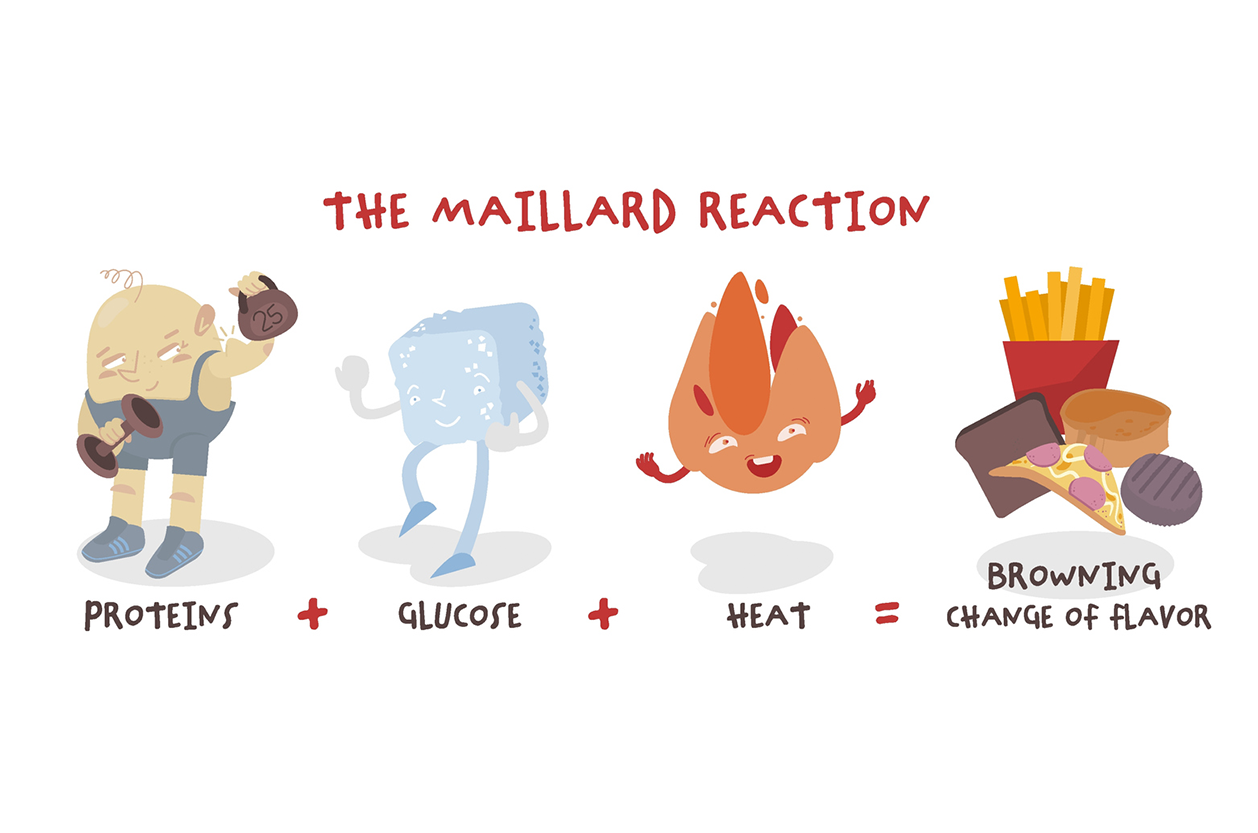

In food, acrylamide forms via a process called the Maillard reaction, where sugars react with proteins under high heat. This creates a browning effect that most people find appealing in flavor, smell, color, and texture. Acrylamide is just one of many compounds formed from the Maillard reaction, but it’s the one implicated in potentially damaging your health.

[Congratulatory note to self: Way to go, overcoming your temptation to make a duck joke in relation to the Maillard reaction. This is a serious subject, and not a cheap opportunity to quack anybody up.]

What Foods Are High in Acrylamide?

As we’ve seen, any food cooked at high heat containing carbohydrates and protein can form acrylamide. How high is high heat? Cooking at 170°C (338°F) or higher qualifies. And the higher the temperature, the more acrylamide forms; so there’s a pecking order of potential concern. Frying heats up food the most intensely, followed by air-frying, roasting, and lastly, baking. (Steaming and boiling don’t make it onto the list at all.)

The major dietary sources of acrylamide include fast and processed foods, thanks to the high heat used in processing and frying them.

Here’s a short list of the foods highest in acrylamide, with the amounts given in micrograms per kilogram (for reference, that’s the same as parts per billion, since a kilogram is one billion times heavier than a microgram):

- Potato chips (211–3515 μg/kg)

- French fries (779–1299 μg/kg)

- Coffee beans (135–1139 μg/kg) or brewed coffee (5.30–79.5 μg/kg)

- Prunes (58–332 μg/kg) and prune juice (186–916 μg/kg)

- Breakfast cereals (<20–639 μg/kg)

- Toast (31–454 μg/kg)

- Crackers (205 µg/kg)

- Cookies (115 µg/kg)

Perhaps most puzzling is the high acrylamide concentration in prunes. But apparently, the Maillard reaction isn’t the only pathway to acrylamide formation. In the case of prunes, the presence of sugars and the relatively high concentration of the amino acid asparagine is also an acrylamide recipe.

Asparagine appears to be a key contributor to acrylamide formation when it appears in a high-carbohydrate food, as it’s found in significant amounts in potatoes, as well as in whole grains (used to make toast and crackers) and some other foods that are high in acrylamide.

Does Acrylamide Cause Cancer?

We can measure acrylamide in parts per billion in any number of foods, but that begs the question: Who cares? Is acrylamide in food something to be concerned about?

In truth, the answer is a bit confusing. Acrylamide is a “probable carcinogen” according to several authoritative sources, including the US Environmental Protection Agency, the US Department of Health and Human Services, the National Institutes of Health, and the International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC).

Sounds like a slam dunk, case closed, right? Acrylamide is bad for you; stay away.

Well yes, kind of. But these evaluations of carcinogenicity refer to the acrylamide from manufacturing, not the kind that occurs due to the Maillard reaction and other chemical reactions in food. And it’s unclear how transferable those evaluations are to food-based acrylamide.

Animal Studies on Acrylamide Carcinogenicity

You might be thinking that it would be illegal for researchers to expose humans to metered doses of industrial acrylamide to see if it causes cancer, and you’d be right. What’s not illegal is to do exactly those kinds of studies on rodents. (Legality and ethics are two different things; our view on the use of animals in medical research.

Rat trials have shown that acrylamide exposure does increase their risk for several types of cancer. But that finding comes with two disclaimers.

First, the doses of acrylamide used in these studies are typically 1,000–100,000 times higher than the usual amounts, on a weight basis, that humans get through dietary sources. The notion that something harmful at high doses is also harmful at lower ones (what scientists call “high-dose to low-dose interpolation”) basically just amounts to a guess. As Food Revolution Summit speaker T. Colin Campbell, PhD, asks rhetorically in his book Whole, “What if the high dose is like getting hit by a car, while the low dose is like getting hit by a Matchbox car?”

Second, nobody knows how animal cancer findings will translate into humans. A 2005 article in the prestigious scientific journal Nature makes the case that it’s foolish to extrapolate carcinogenicity from rodents to humans, for a number of reasons. Lots of things appear to cause cancer in rats and mice but don’t do the same in the human body, and vice versa. In fact, about half of the chemicals known to cause cancer in rats don’t even do so in mice — and they’re a lot more similar to each other than they are to us.

Human Studies on Dietary Acrylamide and Cancer

To be fair, there’s some evidence to suggest that acrylamide might be problematic for humans; our bodies convert it to a compound called glycidamide, which is known to cause mutations and even DNA damage. But studies have discerned differences in how rats and humans metabolize acrylamide into glycidamide, with humans experiencing a two- to four-fold decreased exposure to the latter.

To the rescue — theoretically — come two powerful types of studies: case-control and cohort. These both look at groups of people with different exposure levels to dietary acrylamide and see if there’s a significant difference in their cancer rates. Case-control studies pair two people who are pretty similar except for the amount of acrylamide they get from their food. And cohort studies look at groups of people with different eating patterns, searching for different disease rates between those groups.

To date, neither type of human study has turned up consistent evidence linking dietary acrylamide with cancer. Several studies report no significant association between acrylamide intake and pancreatic, prostate, breast, ovarian, or endometrial cancer. Other studies have found possible links with malignant melanoma, multiple myeloma, follicular lymphoma, esophageal cancer, and breast cancer.

A 2018 study of almost 50,000 Japanese women similarly could find no link between dietary acrylamide and endometrial or ovarian cancer. Meanwhile, a similar 2020 study that followed over 85,000 Japanese men for around 15 years found no association between acrylamide and lung cancer. And researchers in 2022 conducted a meta-analysis that showed no association for a host of non-gynecological cancers in a variety of studies.

Acrylamide and Coffee

In 2018, a California judge ruled that coffee companies must include a cancer warning label on their products, due to the acrylamide that forms during the coffee roasting process. This decision was based on a California law called Proposition 65 which requires businesses to provide a “clear and reasonable” warning before exposing consumers to chemicals known to cause cancer, birth defects, or other reproductive harm. Acrylamide is on this list of Prop 65 chemicals.

For a time coffee companies in California had to include a warning label on their products or face the possibility of legal action. Then in 2019, the Office of Environmental Health Hazard Assessment ruled that chemicals in coffee created during roasting and brewing do not pose a significant risk of cancer — and the warning labels were removed.

This “coffee-acrylamide apparent paradox,” as a 2020 research paper termed it, can serve as a cautionary tale of the danger of looking at compounds in isolation rather than factoring in the complex mixture of biological, dietary, and environmental factors that are always at play.

It seems that roasted coffee, which contains acrylamide, is actually associated with a reduced risk of multiple types of cancer.

How Much Acrylamide Is Safe to Consume?

By this point, you probably won’t be surprised to hear that the answer is, “We don’t really know.” Levels of acrylamide in water are regulated, as is environmental exposure, but dietary acrylamide levels mostly are not, with a couple of exceptions.

California’s Prop 65 has established the Maximum Allowable Dose Level (MADL) to be 140 µg/day. The EU has created a much stricter benchmark for safe levels of acrylamide in food (at least related to the growth of tumors) at 0.17 µg/day per kilogram of body weight. Doing the math, a person weighing 154 lbs (70 kg) could safely consume 26 µg of acrylamide each day. (To put these numbers in perspective, you’d consume around 150 µg of acrylamide in one large order of McDonald’s fries, or 27 µg in a bowl of processed breakfast cereal.)

So how are we doing in relation to these maximum targets? Indexed to that average body weight of 154 lbs (70 kg), data from various European, American, and Asian countries show that the daily intake of acrylamide is estimated to range from 14–70 µg/day for adults.

EU health officials have concluded that current levels of dietary exposure are not a health concern for adults, but may be problematic for toddlers and children. And given that acrylamide is in our water and environment, in addition to many of our favorite foods, it’s likely impossible to completely avoid it. In fact, CDC scientists have found measurable levels of acrylamide in the blood of 99.9% of the US population.

How to Reduce Acrylamide Exposure

Even though we don’t know for sure whether acrylamide in food contributes to cancer in humans, and if so, to what extent, it may still be prudent to exercise caution. For one thing, many of the foods high in dietary acrylamide are processed and fast foods, which can compromise your health for reasons that might have nothing to do with acrylamide. The human body has no nutritional need for french fries or potato chips, and for most of us, the less we eat of these foods, the better.

And there are other simple things you can do to lower your acrylamide exposure from foods like potatoes, bread, and other carbohydrates.

Since acrylamide forms when these foods are cooked above 338°F, you can reduce your risk by cooking foods below that temperature (even 350°F will generate less acrylamide than cooking at, say, 450°F). Boiling and steaming occur at 212°F maximum — the boiling point of water — and a bit higher if you’re using a pressure cooker. Microwaving rarely heats food above 212°F, since it works by bombarding water molecules in food with energy to cook the food that contains them. But there’s evidence that despite the low-temperature cooking done in microwaves, this method can still produce large amounts of acrylamide, especially when on high-power modes.

If you will be cooking your potatoes in ways that trigger the Maillard reaction (especially frying, air-frying, or roasting), cut the raw potatoes into their final shape (cubes, wedges, rounds, or sticks) and then soak them in water for 15–30 minutes before cooking. This reduces their starch content (you’ll notice that the soaking water becomes cloudy from the starch), which helps reduce acrylamide formation during subsequent cooking.

Another way to decrease acrylamide formation in potatoes is to store them in a cool, dark place (like a cellar or cupboard) that is warmer than your refrigerator. At fridge temperatures, the starch in potatoes gets converted to sugar, which turbocharges the Maillard reaction when cooked.

Also, it’s probably wise not to rely exclusively on potatoes for your vegetable consumption. Even without worrying about acrylamide, there’s lots of evidence that the healthiest dietary pattern includes a wide variety of raw, cooked, fermented, and sprouted whole plant foods.

If you’re a fan of toast, choose fermented or sprouted bread, which produces less acrylamide; and set your toaster to lightly brown your bread instead of turning it into something resembling charcoal.

Coffee fans get some good news here: Although coffee forms acrylamide during the roasting process, luckily most of it dissipates when brewing, depending on the process used.

Exercise Caution with Acrylamide

Acrylamide is a chemical compound found in manufacturing, water treatment, and cigarette smoke — and it’s formed in certain foods. In the last few decades, some health researchers and doctors have flagged it as a potential carcinogen. But the research has not definitively proven that it causes cancer in humans.

By and large, regulatory and advisory organizations have not identified safe maximum levels of acrylamide in your diet, although some sources do provide recommendations. And while the link between dietary acrylamide and cancer is unproven, a prudent approach might be to reduce your exposure where possible by shifting away from foods and dishes known to form significant amounts of acrylamide.

Many of the foods that are high in acrylamide, such as french fries and potato chips, have a host of other associated health problems — so regardless of acrylamide concerns, minimizing exposure all around is still likely a good thing for your health.