by Philip Goldman: Growing up in Brooklyn, long before it was “Hipsterville,” I was familiar with three kinds of Jesus…

There was the one and only begotten son of God, Savior of all Mankind, who was worshiped by many of the Irish and Italian Catholics in the neighborhood. And, among the Jews, two alternative versions: the laudable, ethical teacher—a nice Jewish boy, essentially, who met with a terrible fate—and the Jesus they considered a creature of mythology, like Apollo or Zeus.

In my atheistic home, where religion was the opium of the people, Jesus was largely irrelevant, except as a proponent of the “golden rule” and for the horrors that had been perpetrated in his name by misguided followers.

Then came the 60s, and I was introduced to a different Jesus, by way of India. Like millions of my contemporaries, my hot pursuit of truth and personal fulfillment led me to the spiritual legacy of the East. I read the sacred texts of Hinduism and Buddhism, and modern interpreters such as Aldous Huxley, Alan Watts, and Huston Smith. I was drawn to what was called mysticism because I found it, ironically, far less mysterious and far more rational than conventional religion—and even some schools of psychology.

I found a yoga class—not easy to do back then, believe it or not—and learned to meditate. Throughout my explorations, I was surprised to find that Jesus was always referred to with great respect, and sometimes with reverence. That experience peaked when I read Paramahansa Yogananda’s seminal memoir, Autobiography of a Yogi. In it—and even more so in other works, as I discovered later when I researched my biography of him—Yogananda treats the rabbi of Nazareth with such veneration that I couldn’t help thinking: What have I been missing?

So, I read the New Testament. It blew my mind. Because my spiritual reference point was more Hindu than Judeo-Christian, the Gospels came off the page like the Upanishads or the Bhagavad Gita, not like churchy dogma. The main character was a master teacher—a guru—who guided his disciples not just to better behavior but to union with the divine. His term for the infinite Ground of Being was “Father,” but it was easy to evoke the language of the Vedic seers and substitute Brahman or Ishvara or the Self.

When he tells the crowd at the Sermon on the Mount not to pray conspicuously like the hypocrites, but to “go into your room and shut the door and pray to your Father who is in secret,” I saw a guru directing his disciples to meditate in silence. This was a Jesus I could live with: exalted in a way that befits someone whose impact on history is unparalleled, but without the singular cosmos-shaking agenda or the religious triumphalism that relegates nonbelievers to either irrelevance or damnation.

I soon learned that Hindus in general, and the gurus and yoga masters who came to the West in particular, tended to see Jesus as a satguru (true teacher) and an enlightened yogi of the highest order. Some even afforded him the status of avatar, placing him on the same level as Krishna and Rama in the pantheon of divine incarnations.

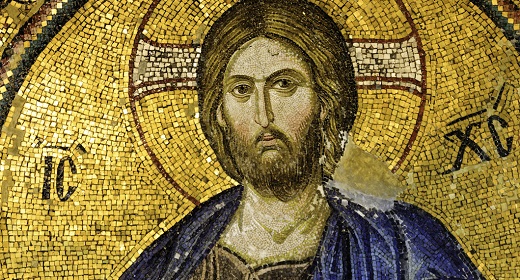

To them, the teachings of Christ, followed properly and deeply, is a legitimate pathway to the unified awareness that is yoga’s true aim. That is why, in many spiritual institutions with Indian roots, you will find images of Jesus placed alongside the Buddha and other saints and avatars. In Yogananda centers, in fact, a portrait of Jesus is on every altar, alongside one of Krishna, Yogananda himself, and the three venerated gurus in his lineage.

This way of seeing Jesus has been filtering into America’s bloodstream ever since the 19th Century when Henry David Thoreau equated Jesus and Buddha and called himself a yogi. It gathered steam as a stately parade of gurus arrived on our shores, and it exploded after the Beatles’ 1968 sojourn in India. By now, that perspective has affected millions.

For a great many angry or alienated Christians, it has been the key to reconnecting with their religious heritage on terms they can live with. Even people whose religious orientation is, for all practical purposes, Hindu have been encouraged by their gurus to honor their Christian roots, often by thinking of Jesus as their ishta devata (preferred form of God). In that context, many prodigal sons and daughters have found their way back to the Jesus they love by way of India. Similarly, thousands of Jews who studied Hinduism or Buddhism have come to see Jesus as a great mystical rabbi and a passionate reformer, not as the founder of a hostile cult.

The image of Jesus as a sage and sadhguru may not sit well with clerics for whom Christ can only be the one true messiah and the great hinge of history. They ought to be glad that millions who might otherwise view this season as merely a respite from work, or as nothing but humbug, will instead celebrate the birthday of a great, holy man. That’s what I’ll be doing.

Each December it makes the season merrier, jollier, and brighter. That and The Drifters’ version of “White Christmas.”