You won’t see it on showroom floors, but BMW is putting faith in its new SUV

Hydrogen-powered cars constitute a drop in the world’s ocean of 1.47 billion cars. The same goes for renewable “green” hydrogen fuel, or any infrastructure to effectively deliver it to vehicles or power their factories. But despite rampant skepticism in some corners, BMW is among the automakers and policymakers convinced that our lightest atomic element holds a key to achieving carbon neutrality—for our personal cars, commercial trucks, and the energy grid itself.

Hydrogen-powered cars constitute a drop in the world’s ocean of 1.47 billion cars. The same goes for renewable “green” hydrogen fuel, or any infrastructure to effectively deliver it to vehicles or power their factories. But despite rampant skepticism in some corners, BMW is among the automakers and policymakers convinced that our lightest atomic element holds a key to achieving carbon neutrality—for our personal cars, commercial trucks, and the energy grid itself.

The Bavarian automaker has launched a pilot fleet of iX5 Hydrogen SUVs in South Africa, expanding a “world tour” for the iX5 that kicked off in Antwerp, Belgium. Billed as the world’s most powerful fuel-cell vehicle, the iX5 is based on the X5, which has an internal-combustion engine and is among BMW’s best-selling models.

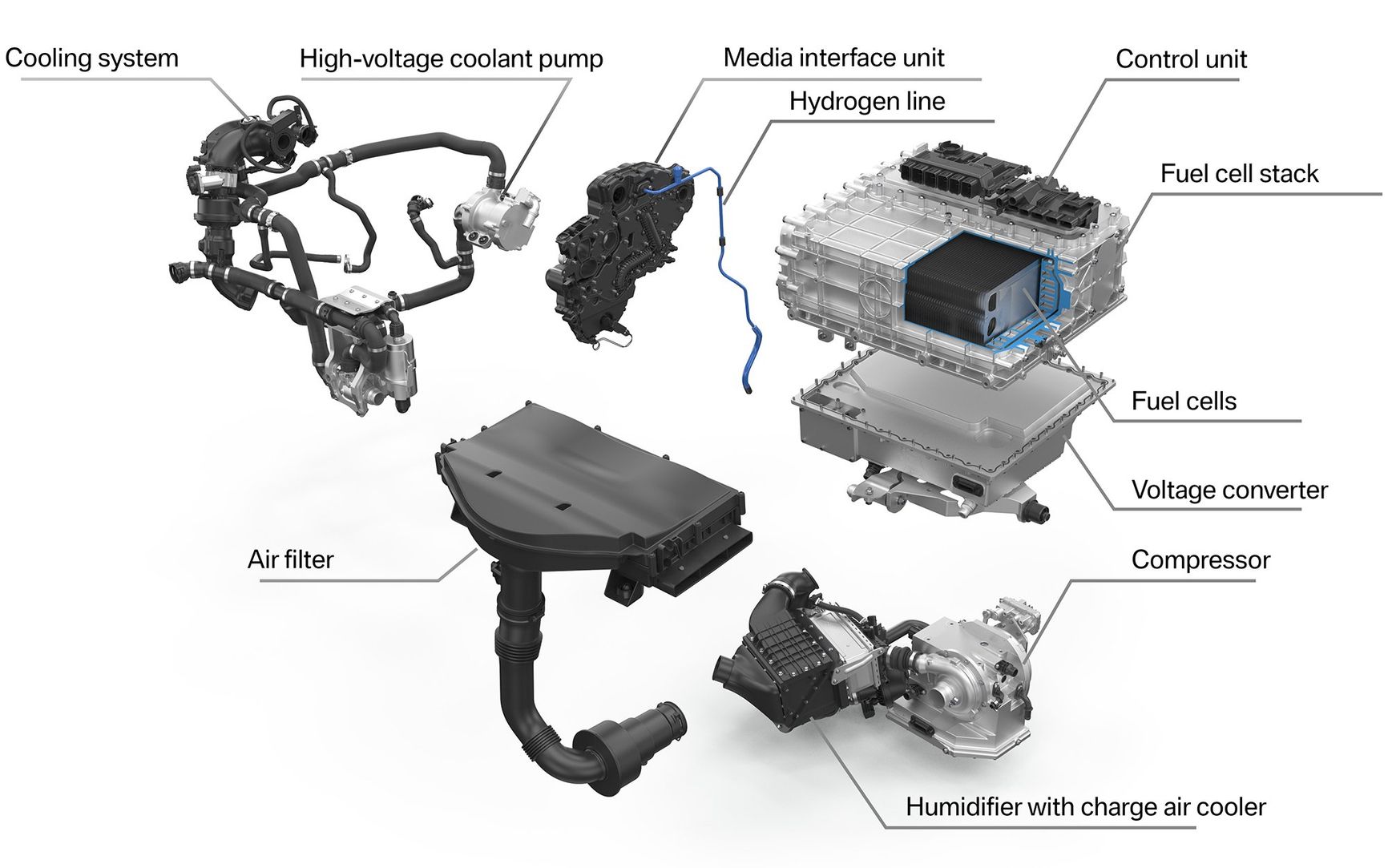

The iX5 eschews a combustion engine in favor of a 125-kilowatt (170-horsepower) fuel-cell stack. That stack powers an electric drive unit, using BMW’s fifth-generation eDrive technology, at the rear axle. Below the X5’s floor, a massive pair of carbon-fiber-reinforced plastic tanks hold 6 kilograms of hydrogen, pressurized at a hydrogen industry standard of 700 bars (70,000 kilopascals).

BMW’s hydrogen system comes together in Munich and generates 295 kW (401 hp) in the iX5.BMW

Coincidentally—and ideally for doing conversions in your head—one kilo of 700-bar hydrogen contains almost precisely the energy of a gallon of gasoline. A tiny 2.5-kilowatt-hour battery, roughly the size of those in non-plug-in hybrids, supplements power gaps from the fuel cell with a maximum 170 kW (231 hp) of its own. That brings total system output to a robust 295 kW (401 hp), enough to reach a top speed of 180 kilometers per hour (112 miles per hour). Regenerative brakes capture kinetic energy, helping boost the iX5’s total driving range to 504 km (313 miles) on Europe’s Worldwide Harmonised Light Vehicle Test Procedure cycle.

Last year, BMW gave me a fascinating glimpse of its Hydrogen Competence Center as it readied the iX5 Hydrogen for its global development tour. The iX5 has visited nearly every continent and will now reach Australia in 2024, aiming to raise awareness about hydrogen’s role in the energy transition. The iX5 emerges from the nearby Munich Research and Innovation Center (FIZ), where every concept car from BMW Group brands takes shape, including models on the path to showroom production. About 900 employees work at that pilot plant, where BMW has produced fewer than 100 iX5 vehicles so far.

Those fuel-cell operations are a short drive from the century-old Munich factory that BMW is transforming into a leading-edge facility. An ultimate goal is to power that factory and others with renewable energy, including from hydrogen. BMW is the first German automaker to sign onto the United Nations’ “Race to Zero” pledge, with BMW determined to become fully carbon neutral by 2050. And BMW executives and engineers seem convinced that without hydrogen in the energy mix—including for personal and commercial trucks that may be poorly suited to battery propulsion—the transportation sector, and nations in general, have almost no chance to stem the rise of global temperatures.

“Hydrogen is a versatile energy source that has a key role to play,” said Frank Weber, a member of BMW’s board of management. “We are certain that hydrogen is set to gain significantly in importance for individual mobility.”

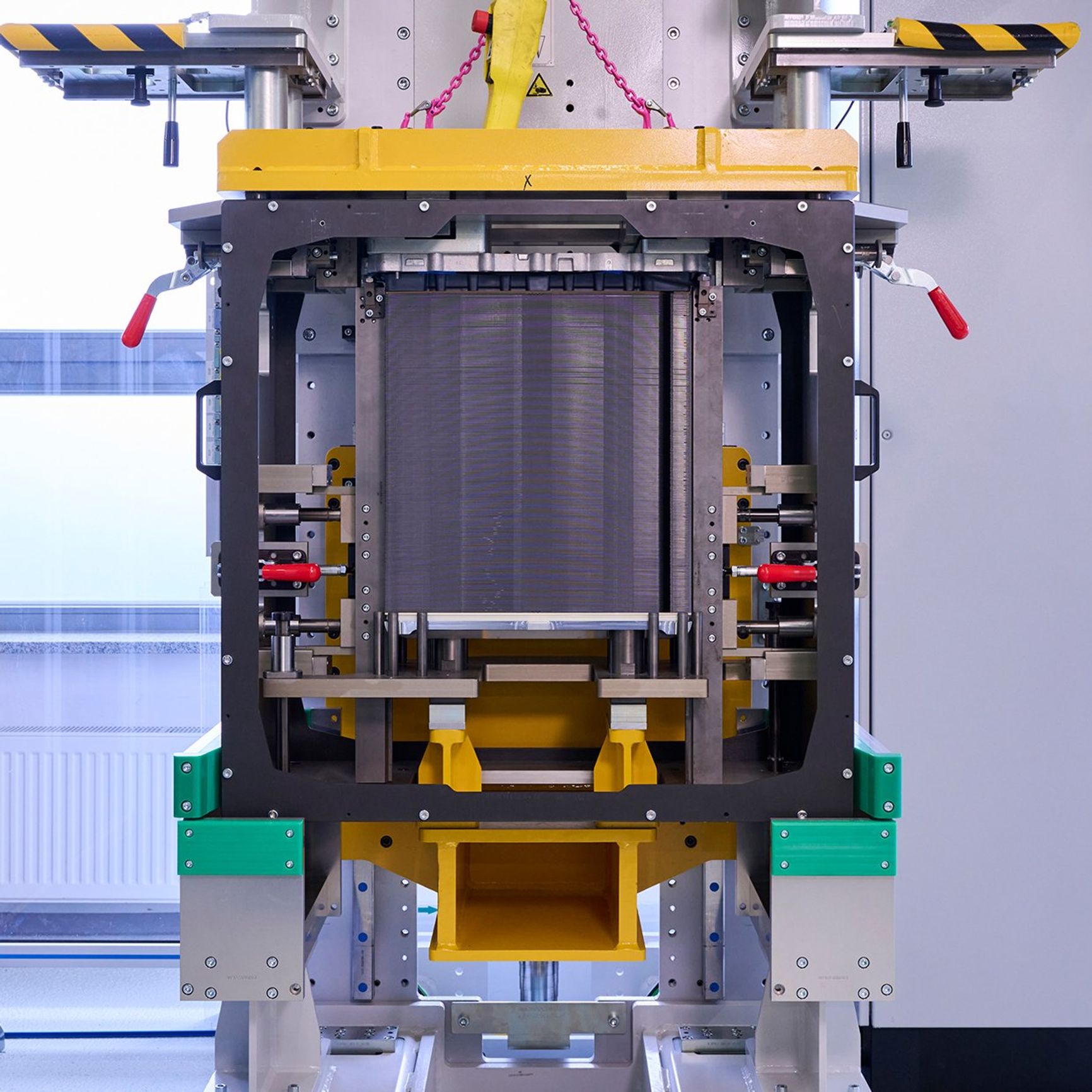

BMW’s fuel cells are designed in-house, but they start with fuel-cell plates from Toyota, the same found in the subcompact Toyota Mirai. Those wafer-thin plates—roughly the size and shape of an A/C filter—are precisely stacked by an automated machine that compresses hundreds of plates together. Another machine inspects individual cells to ensure no hydrogen escapes, as the gaseous element is prone to do. That fat stack of cells is sealed in a sand-cast housing and mounted in a rear carrier of the iX5.

An iX5’s fuel-cell stack is assembled via an automated process.BMW

An iX5’s fuel-cell stack is assembled via an automated process.BMW

An electric compressor, similar to a turbocharger, squeezes hydrogen fuel into the stack of plate membranes, where a catalyst separates hydrogen molecules into protons and electrons. The protons and electrons take separate paths to a battery cathode, where electrons create the flow of electricity, with water vapor as the sole by-product.

Perform the aforementioned conversion and the BMW’s onboard hydrogen returns the equivalent of 26.4 kilometers per liter, or 62 miles per gallon—more than 2.5 times the energy efficiency of an X5 xDrive 40i and its gasoline six-cylinder engine. And in theory, refilling your tank from a hydrogen pump takes less than 5 minutes. Take that, EVs.

BMW Group—which includes the Mini and Rolls-Royce brands—sold a record 376,000 battery-electric vehicles (BEVs) worldwide in 2023, a 74 percent jump from 2022. That lifted BMW’s BEV sales to a healthy 15 percent of a 2.5-million-car total, easily outpacing electric percentages and totals at its German rivals Mercedes-Benz and Audi. Despite those booming sales, Juergen Guldner, BMW’s general program manager for hydrogen technology, said hydrogen cars aren’t either-or competitors with EVs but rather a complementary tech.

“Since hydrogen cars combine the advantages of electric driving with the possibility to refuel quickly, they would be ideal for customers who travel a lot or do not have electric charging at home or work,” Guldner said.

The “possibility” of quick fuel stops runs smack into a problem, however: Compressed hydrogen remains unavailable to the driving public in any real sense, with fewer than 350 public stations in the United States and the European Union combined. And fuel-cell cars essentially don’t exist in showrooms and are limited to minuscule fleets for beta-testing customers of Toyota, Honda, and a few other brands. Since almost no fuel is generated for retail, hydrogen is extremely expensive, raising per-kilometer driving costs to at least double the price of gasoline. And for now, hydrogen is sourced almost entirely from polluting natural gas or other fossil fuels, blunting any potential environmental edge.

Proponents such as Thomas Hofmann, a BMW hydrogen manager, acknowledge every hurdle. But Hofmann and other experts have come to believe that EVs and their infrastructure can’t possibly serve every vehicle or use case, whether for consumers or cargo hauling. Several experts concur, including an International Energy Agency report that highlights hydrogen’s potential in the energy transition, including transport and storage.

Electricity “is unlikely to work 100 percent of the time,” Hofmann says.

Though BMW has harnessed hydrogen for a showroom-style SUV, the company views still medium-to-large trucks as hydrogen’s most favorable application.

“The heavier and larger the vehicle, the more hydrogen makes sense,” Hofmann says, because EV batteries deliver diminishing returns in range and cost at that point.

To that end, backers say hydrogen could fill gaps in transportation and power generation that other renewables can’t match. Hydrogen can be cheaply stored and transported via pipeline. It can diversify the energy supply chain and guard it against shortages. Hofmann coauthored a white paper on the budding hydrogen economy for VDE Renewables. From the paper:

Electricity generation from wind and solar is subject to strong daily and seasonal fluctuations. The potential to produce green electricity also varies greatly geographically. Hydrogen provides an optimal solution for bridging the gap between volatile generation and the need to supply green energy on-demand across all sectors.

As for a near-absence of renewable hydrogen, a McKinsey & Company analysis argues that green hydrogen’s price will quickly fall below that of fossil hydrogen as market penetration grows. Backers cite growing governmental and environmental support for hydrogen, such as President Biden’s bipartisan infrastructure law and the Paris climate accords. The E.U. has readied rules calling for a minimum number of hydrogen stations. Hofmann’s study projects a US $240 billion global investment in hydrogen through 2030.

Hofmann’s paper does caution that today’s hydrogen investment remains largely driven by global subsidy supports. And in a major understatement, the paper cites major uncertainty over expected return on private investment in hydrogen.

That uncertainty extends to showrooms. For now, BMW’s iX5 is strictly a testbed for the tech. But the automaker intends to bring its first series-production fuel-cell car to showrooms by 2030. Which is around the time BMW projects having 10 million EVs on the world’s roads, and ideally the charging infrastructure to match. For hydrogen, that’s a lot of catching up to do.