by Neil Crossley: The story of Wichita Lineman

Jimmy Webb was driving through the high plains of north-west Oklahoma when the inspiration for his biggest ever song came to him.

It was a scorching summer afternoon and as the Grammy award-winning songwriter drove, vast swathes of grassy landscape stretched for as far as the eye could see. The terrain was flat and featureless, except for telephone poles positioned at the side of the road all the way to the horizon.

In the distance, Webb noticed a man perched near the top of one of these poles. As Webb got closer he could see the man was holding a phone and talking into it. The image of this anonymous lone figure toiling in searing heat in this vast landscape stuck in his mind as he drove on.

Webb knew this utility worker was a ‘lineman’, employed to check the telephone lines. But he began to wonder if the man might actually be talking to his girlfriend far away, and what was going through his mind as he worked in total isolation out on the high plains.

“It was such a curiosity to see a human being perched up there,” he told Blender magazine in 2001, as reported by Michael Hann in the Financial Times, in “an area that’s real flat and remote, almost surreal in its boundless horizons and infinite distances”.

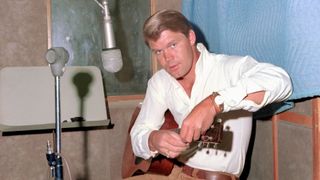

This image would inspire Jimmy Webb to write Wichita Lineman, a haunting, mercurial ballad that would become a massive mainstream hit for country crossover star Glen Campbell. The song, with its sweeping melancholy, is one of the most perfectly realised pop songs of all time. Almost six decades on from its creation, it has a powerful and enduring legacy.

It was February 1968 when Jimmy Webb received a phone call from Glen Campbell, a singer, songwriter and former session guitarist with the ‘Wrecking Crew’, the loose collective of gifted LA session musicians who played on hundreds of Top 40 hits in the 60s and 70s, such as Be My Baby by the Ronettes, You’ve Lost That Lovin’ Feelin by the Righteous Brothers, California Dreamin by The Mamas & the Papas and Good Vibrations by the Beach Boys.

They also played on By the Time I Get To Phoenix, a Jimmy Webb composition that was a hit for Glen Campbell in 1967. When Campbell called up Jimmy Webb in February, 1968, he was midway through recording an album and looking for his first Top Ten hit.

“Do you think you could write us another By The Time I Get to Phoenix?” Campbell asked, according to Neely Tucker at the US Library of Congress. Webb liked a challenge. “Okay,” he said. “Let me see what I can do.”

By then, Webb was living high in the Hollywood Hills, in an old mansion that he shared with numerous friends and a green baby grand piano. He was still basking in the success of Up, Up and Away, his Grammy-award winning song, recorded by the 5th Dimension.

Webb went to his piano and decided that a geographical reference in the title might work again. He recalled the image of the lone telephone worker on that long, lonely stretch of road in Oklahoma. Over the next two hours he sketched out a song and asked Campbell and De Lory to drop by his house that evening to take a listen. “It’s not finished yet,” said Webb as they sat down. “There’s no third verse.”

When Webb played them the song, Campbell was bowled over. He knew in an instant that it was a hit. “When I heard it I cried,” he told BBC Radio 4 in 2011. “…It’s just a masterfully written song.”

At its core, Wichita Lineman is a story of desolation and longing: “I hear you singing in the wire / I can hear you through the whine”. As Neely Tucker of the US Library of Congress puts it, the song “spoke to the human condition, the universal need for love. The imagery about the singing in the wires and searching in the sun for overloads was out of this world”.

The song has just sixteen lines and lasts three minutes and six seconds but it says more in that time than many authors manage in a lifetime. It also includes a couplet that author Dylan Jones, in his acclaimed 2019 book The Wichita Lineman: Searching in the Sun for the World’s Greatest Unfinished Song, calls one of the most exquisite romantic couplets in the history of song: “And I need you more than want you / And I want you for all time”.

“I was trying to express the inexpressible,” Webb told Jones in September 2019, in an interview published in the Literary Hub, “the yearning that goes beyond yearning, that goes into another dimension, when I wrote that line”.

Within days, Campbell and De Lory had assembled top session players from the Wrecking Crew in the Capitol Studios’ vast ground floor Studio A in the iconic 13-storey Capitol Tower building, just north of the intersection of Hollywood and Vine.

On drums was Jim Gordon, who had played on Pet Sounds and would go on to work with John Lennon, George Harrison, Traffic, Steely Dan and Frank Zappa.

Jimmy Webb played keyboards and on rhythm guitar was Al Casey, who had worked with artists such as Gene Vincent and Carl Perkins. Also on guitar was Glen Campbell himself.

Completing the line-up was legendary bassist Carol Kaye. As the session started, Kaye looked at the charts De Lory had handed out and felt something was missing at the beginning of the song. She suggested a six-note descending bass riff as an intro and in that moment created one of the most iconic intros of all time.

Kaye used a hard pick on medium gauge flat-wound strings and the instrument that she used was a six-string solid body Danelectro bass. The trebly tone of the Danelectro lent the track a distinctive sound and segued perfectly into the lush, sweeping strings.

Jimmy Webb discusses the impact of Kaye’s bass intro in Dylan Jones’ book. “Now that’s an intro,” says Webb. “It has a function. There’s a reason for it. On the radio, it lets people know, ‘oh, it’s that one, it’s that story that I like, I’m going to listen’.”

Kaye repeated the same bass motif throughout the song and kept things simple, as she explains in Jones’ book. “It was amazing to create a nice bass line for it, but everybody makes out that that lick I played was so good. They asked me to play a lick so I played a lick. You keep the bass line simple when the tune is especially good and add a few nuances here and there as a framework. You’re there to make the singer and not to over-shine them.”

Campbell liked the sound of the Danelectro so much that he asked Kaye if he could borrow it for the guitar solo he had in mind for the middle section that Webb had yet to deliver. It was an inspired decision.

Campbell’s simple solo, with its tremelo-soaked sound, follows the top line vocal melody, accentuating the song’s lonely, melancholic feel

One of producer Al De Lory’s contributions to the track was the sweeping violins that evoke the vast, empty space and the loneliness of the lineman. De Lory used some of Carol Kaye’s bass improvisations for the string arrangements.

The sonic icing on the cake though was Jimmy Webb’s Gulbransen electric keyboard, which emulated the sound effect of a telephone signal travelling along a wire. Webb showed Campbell what this instrument could do up at his house in the Hollywood Hills.

“Glen said ‘Here at the end I want it to sound like that record Telstar by The Tornadoes…’,” recounts Webb in Dylan Jones’ book. “…I just held two notes down and the organ automatically takes these two notes, either a fourth or a fifth, and it cycles them up and down the keyboard… it’s a very shivery, icy, almost like outer space kind of sound. Glen went crazy and said ‘We have to get that, we gotta put that on the fade’.”

The instrument was duly hauled over to Capitol Studios. “We recorded it and that’s the sound people associate with this record,” said Webb. “… it was just me holding down two notes, which was exhilarating.”

When Jimmy Webb originally showed Campbell and De Lory the song, he was convinced that it still needed a third verse. He certainly felt it wasn’t finished and said so in the note he enclosed with a tape of the song that he sent over to the studio. To emphasise his point, Webb drew a skull and crossbones on the note.

Webb heard nothing back and then a few days later, he bumped into Campbell on the set of a commercial for General Motors. Webb invited Campbell back to his house in the Hollywood Hills to hear some other songs. Webb asked about Wichita Lineman, reiterating that it wasn’t yet finished. “Well it is now,” replied Campbell, pulling an acetate of the song out of his holdall.

When he put the acetate on a turntable Webb could not believe what he was hearing. From Kaye’s intro to the sweeping strings and Campbell’s stunning vocal performance, his song sounded sublime. As verse three rolled around, the one that Webb had yet to write, he realised they had simply added a solo. “Glen had detuned a guitar down to a ‘slack’ key, Duane Eddy style, and simply played the melody note for note, which was an extreme compliment,” said Webb in Dylan Jones’ book.

Wichita Lineman was released on 26 October, 1968 and reached No. 3 in the US and No. 7 in the UK charts. In the years and decades that followed the song’s appeal has transcended genres and generations. As BBC Radio 2 put it in 2011: Wichita Lineman is “one of those rare songs that seems somehow to exist in a world of its own – not just timeless but ultimately outside of modern music”.

Bob Dylan reportedly called it “the greatest song ever written”, as noted on the cover of Dylan Jones’ book.

In 2020, Webb spoke to Allen Morrison of American Songwriter magazine about the enduring power of the song. “Billy Joel came pretty close one time when he said ‘Wichita Lineman is a simple song about an ordinary man thinking extraordinary thoughts’. That got to me; it actually brought tears to my eyes. I had never really told anybody how close to the truth that was.”

Awaken Music

Awaken Culture

Awaken Spirit

Source: AWAKEN