by Candice Elliott: There is a lot of misinformation about the 10,000-hour rule theory of self-improvement, and it turns out now all 10,000 hours are the same…

We delve into the truth behind the 10,000-hour rule and show you how to become great at anything.

The 10,000-hour rule is not really about the number of hours you put into something; it’s about deliberate practice. If you want to become great at anything, it matters more how you practice than how much you practice.

What is the 10,000-Hour Rule?

The 10,000-hour rule has been a topic of scientific research since the 1970’s but it came into the mainstream when Malcolm Gladwell wrote about it in his book Outliers. The rule is based on research into the abilities of top performers in various fields like mathematics, chess, tennis, swimming, and music.

The research shows that for the overwhelming majority of experts who reach the top of their fields (for instance, chess grandmasters or great composers) have spent a minimum of ten years acquiring and honing their skills.

The few who are exceptions to this rule are found to hit their expert status in year eight or nine of their careers—not far short of the average. So being a prodigy with a “gawd given” talent is just a myth.

Only one who devotes himself to a cause with his whole strength and soul can be a true master. For this reason, mastery demands all of a person.

10,000 hours works out to be around 20 hours per week for ten years. Ten years is a long time but 20 hours a week isn’t so bad especially when you consider the average American watches five hours of television a day.

Deliberate Practice

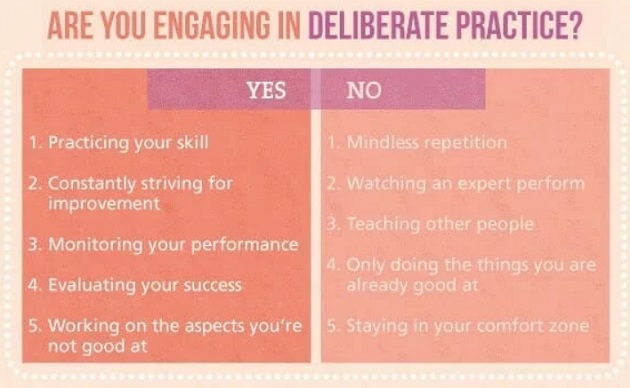

The problem with the popularity of this 10,000 hours idea is that it’s often misunderstood as “any 10,000 hours” spent on your skill or craft. But not all practice is the same: there’s a big difference between mindless repetition and what scientists call deliberate practice.

A fascinating exception to the 10,000-hour rule is Magnus Carlsen, the youngest chess player ever to reach a number one world ranking. Carlsen played computer chess to amass a huge amount of deliberate practice in a short period of time—so, although it seems as if his talent is innate because he reached expert level at such a young age, what he really did was accelerate his learning process by focusing on the right type of practice all the time and by getting constant feedback.

“ Perhaps the greatest difference between deliberate practice and simple repetition is this: feedback. Anyone who has mastered the art of deliberate practice—whether they are an athlete like Ben Hogan or a writer like Ben Franklin—has developed methods for receiving continual feedback on their performance.”

Part of the reason deliberate practice is so important is that it helps us to encode information about what we’re learning more carefully. Research has found that one of the significant differences between highly skilled experts and amateurs is how well information about their field is categorized in their brains.

Top-level experts can access relevant information faster and more reliably, due to spending time in highly-engaged, deliberate practice of their craft.

3 Types of Deliberate Practice

Thomas recently wrote an article detailing how to learn any new skill quickly. He breaks down deliberate practice into three stages.

The Cognitive Stage: This is the first step when learning a new skill. You’re practicing and making mistakes.

The Associative Stage: You’ve had enough practice to see where you are making mistakes and to correct them. It’s at this stage that getting the quality feedback we spoke about earlier is important if you want your skill level to progress.

Autonomous Stage: When you reach this stage, you can almost perform the skill on auto-pilot. You aren’t a master yet and maybe you never will be but you have become competent in a relatively short amount of time thanks to deliberate practice.

Virtuoso violinist Nathan Milstein once said, “Practice as much as you feel you can accomplish with concentration. Once when I became concerned because others around me practiced all day long, I asked [my professor] how many hours I should practice, and he said, ‘It really doesn’t matter how long. If you practice with your fingers, no amount is enough. If you practice with your head, two hours is plenty.’”

Take a Risk

The real reason most people will never become a master at any skill is that they won’t take a risk, they won’t leave their comfort zone. If you want to become great at something you have to put yourself out there. You may very well fail. But you can only succeed because of your failures.

Find your motivation. Getting good at something takes time and effort. You might also experience some setbacks along the way. That’s why it’s crucial that you find your motivation: it helps you get through the difficulties.

Know how to measure progress. To get good at something, you must know how good is measured. What are the metrics? How do you know that you are making progress? Knowing those things will help you focus your effort.

Learn from the winners. Don’t waste your time with trial and error. Instead, find out how the winners do it. In Andrew’s case, he read articles from evaluation-contest winners to learn how they did it. Who are the winners in your field? Learn from their experiences.

Practice. It’s not enough just to know what to do; you must also apply it. You will never be good at Spanish unless you practice.

Take risks. To get good at something, you must take risks. Not taking risks, not being uncomfortable means not growing. Learn from the lobsters!

How Do You Get to Carnegie Hall?

Practice, practice, practice.

First, you must learn it by reading or listening to others who know how to do it, but most especially by doing. “Borrow” ideas from other people who are already successful, run them through your own filter, make them your own.

That’s not only how you get better but how people improve on existing products. There is no need to reinvent the wheel but you can improve the wheel.

Then do some more. At this point, you’ll start to understand it, but you’ll suck. This stage could take months. Do even more. After a couple of years, you’ll get good at it.

Do some more. If you learn from mistakes and aren’t afraid to make mistakes in the first place, you’ll go from good to great.

Be Deliberate

If you are going to do something, you want to do it well. But all of us only have so much time to devote to practicing to get better at something. The key is to practice in a deliberate way, not to be afraid to take a risk or make mistakes and to seek out feedback.

If you put in the hours and practice deliberately you can master anything.