by Corinne Oestreich: Native Americans don’t just live on reservations, we live in cities, and we live internationally…

I grew up in the Silicon Valley of California. I was born in the city and have lived here my whole life, as an “Urban Native.” My grandfather moved to California from Mohawk territory in the 1950s after he served in Korea, and we have all lived in Sunnyvale ever since.

The challenges I grew up around were different from my Oyaté (family) out on the reservations. It is easier to lose our sense of culture living among so many established settler communities. If I didn’t find my community, my Native family or my traditional support, I’d get swallowed up by colonialism.

As a child, Thanksgiving was for me what it is for most children ― a day when you spend time with family, talking or thinking about what you’re thankful for. You color some turkey pages and then you eat a lot of food. My family worked really hard to keep the narrative of the dinner between Indians and Pilgrims out of it. The only time I was exposed to this story of a dinner between Pilgrims and Indians was when I was in elementary school. Growing up in an established settler community like the Bay Area, I was not given much perspective on the holiday. I was told: “This dinner happened. Here, wear this paper feather headdress and let’s eat some cookies bought at Safeway.”

If I didn’t find my community, my Native family or my traditional support, I’d get swallowed up by colonialism.

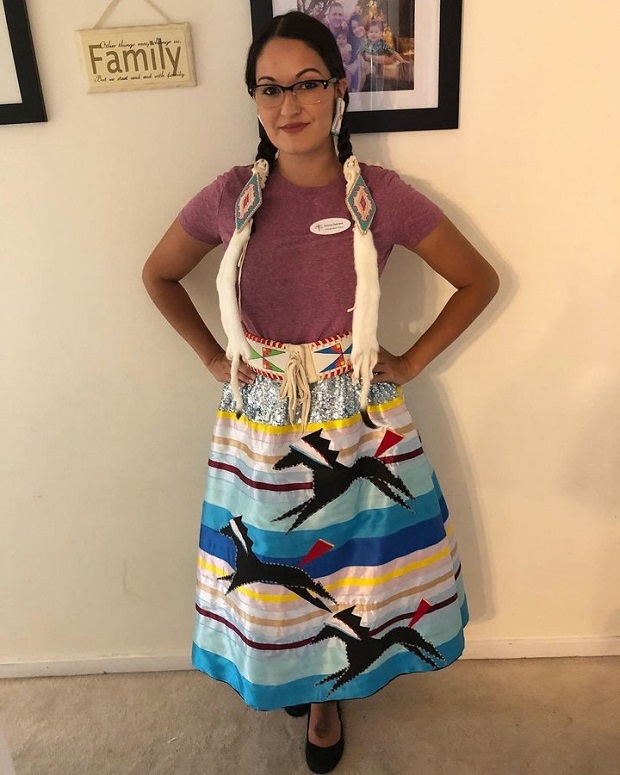

As my younger brother and I grew into adults, we both dove headfirst into learning as much as we could from our elders about our cultures. That desire really intensified after I gave birth to my first child. The need to pass down traditional knowledge grew from that awakening into motherly responsibility. We wanted to honor our ancestors with respectful knowledge and practice. I am Lakota and Mohawk, two very different cultures, so there was much to learn and many opinions that came with it.

I became heavily involved with the Bay Area Native community and attended powwows and ceremonies in San Francisco and San Jose. I talked with as many elders as I could find. I researched my own history as well as my tribal nation’s history and its governments. A side effect to gaining more of that traditional knowledge was fighting the anger that came creeping in along with it.

I found myself dwelling on the pain of what I learned. I became angry and bitter during the holiday and ashamed to celebrate with my family when Thanksgiving rolled around. I especially struggled with this anger around the Thanksgiving holiday when I worked as a resource aide in an elementary school.

I remember the first time I saw a small kindergarten boy walk out of his classroom at the end of the day wearing a feather headdress made from construction paper. It was November, and I had been working at the elementary school for only two months when I saw him come skipping down the hallway with his backpack, purple and green cut feathers flapping back and forth across his blond head.

I froze. It had been years since I was in elementary school myself, and I had completely forgotten about this approach to celebrating Thanksgiving in our schools. I felt sick; I distinctly remember looking at the faces of the parents around me thinking, “Is no one else upset by this?”

This happened to be the same time as the protests at Standing Rock, and all of the violence my friends went through was a stark contrast to this skipping boy. Here I was sneaking out on my breaks to watch my friends at Standing Rock get sprayed by ice cold water, beaten by police officers, thrown in dog kennels and bitten by security dogs, all while praying and wanting clean water, while another generation of children was being shown that dressing up as an “Indian” was fine on Thanksgiving. I realized the holiday was lifted on some imaginary pedestal as a joyous day of peace between two worlds, when historians know the truth to be much more violent.

I realized the holiday was lifted on some imaginary pedestal as a joyous day of peace between two worlds, when historians know the truth to be much more violent.

At a Veterans Powwow in 2016, I expressed this anger and pain to an elder. This elder was a veteran and was attending the powwow specifically to participate in the “Wiping of Tears” ceremony. This is a healing ceremony that veterans participate in when healing from trauma or post-traumatic stress disorder. It’s part of their recovery from war and from service, and it addresses the release of a lot of anger. This elder took my hand while I waited with them for the ceremony and offered an opinion to me that challenged the anger I had developed for the Thanksgiving holiday. The elder said, “You can choose how you feel about this day, but it is a choice. Either let the day claim you, or choose to reclaim it.”

I can remember being taken aback by that statement. Can I choose to reclaim this holiday? Doesn’t that dishonor my relatives who have died because of those who came here as Pilgrims? Or maybe I dishonor them by holding on to anger.

So what could I do, or bring to my family, that would reclaim the day in a way that was both healing and power-giving? My family decided that we would spend the day celebrating the survival of our culture, our language, our foods. This was a decision I made for myself personally. I know that many in my nations are not at a place where they can approach Thanksgiving in this way, but for myself, and for my children, this works. There are also ceremonies ― like the Sunrise Ceremony on Alcatraz Island ― within the Bay Area Native community that help embrace healing on Thanksgiving.

So what could I do, or bring to my family, that would reclaim the day in a way that was both healing and power-giving?

The first time I attended the Alcatraz Sunrise Ceremony in San Francisco was in 2017. The Sunrise Ceremony is a special event organized by the Muwekma Ohlone people of San Francisco and other Bay Area Natives, to come together as a community in the darkness of Thanksgiving morning and partake in the reclamation of the holiday for our surviving people. There is always a large, warm bonfire in the center and a circle of relatives and guests that surround it.

The ceremony has many powerful speakers all focused on the positive reclamation and healing of the day. By the time the sun begins to rise, we raise our palms to the coming light and welcome the power of that healing. Last year at the ceremony, I happened to be standing beside former NFL player Colin Kaepernick, only realizing it after the sunlight began to illuminate those around me. He was there to observe and learn. Through natural conversation, I was gifted the opportunity to be able to share with Mr. Kaepernick some of the teachings of my cultures.

There was a moment after the ceremony when the two of us were walking through some of the restricted area on Alcatraz to see a mural painted by Alcatraz occupiers in the 1970s. He asked me what my opinion was on Thanksgiving, and the holiday in general. The only answer I could give him on that walk echoed the words of the elder that challenged my own feelings the year before: “I can choose how I feel about this day, but it is a choice. I can either let the holiday claim me, or choose to reclaim it.”

If I could ask one thing from my non-indigenous fellow Americans when it comes to Thanksgiving, I would ask that you refrain from teaching the romanticized version of the holiday. Read to your children about what it means to be thankful, what it means to heal and be a family. Learn as a family about the tribal nation that is local to where you live. Take time during dinner to recognize whose traditional lands you give thanks on. Take this holiday into your own hands and understand that not every Native will have good feelings about this day, and be accepting of that. We can all choose how we feel about this holiday, but it is always our own choice.