by Alexa Erickson: Are you religious? Spiritual? Purely scientific?

These are the types of questions that arise amongst people trying to find connections, or simply learn more about another. And if someone were to say, “I’m Buddhist,” it may likely fall outside of the realm of anticipated answers.

There’s a big questioning surrounding Buddhism: Is it a religion, or is it a philosophy?

But answering that question isn’t so easy, because Buddhism doesn’t fit neatly into just one category. In fact, when Buddha was asked what he was teaching, he responded by saying that he teaches “the way things are.” He advised that people should not believe his teachings merely out of faith, but should digest his words and, through careful examination, determine for themselves if and how they fit into their own lives.

This sounds a lot like science: “The intellectual and practical activity encompassing the systematic study of the structure and behaviour of the physical and natural world through observation and experiment.”

Read: observation and experiment.

It’s intriguing to think how Buddha’s words can fit into the fundamentals of belief. He advised people to not simply follow suit because someone preached. If we were to do so in other parts of our lives, what would we have? A two-party system? Yes. Social norms? Yes. Taboos? Yes.

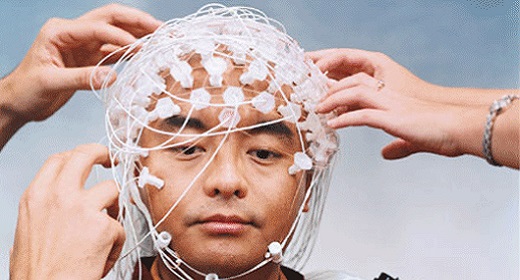

The Dalai Lama and other Buddhist teachers have rebranded Buddhism for the modern day world. People seek to counteract their cluttered minds and fast-paced lifestyle with mindfulness, and Buddhism has emerged as the answer, backed by science. Numerous studies now exist that promote the benefits of mindfulness techniques.

Could it be that Buddhism surpasses traditional labels? Is it more of a science of happiness?

Or, perhaps, Buddhism as we know it, as many of us use it, differs significantly from the origination of Buddhism. For instance, modern Buddhism is the result of transformed tradition, where an affinity for scientific understanding reigns supreme.

Robert Sharf, a scholar of Buddhist studies at UC Berkeley, weighed in on the subject:

…the critiques of religion that originated in the West resonated with [Buddhist’s] own needs as they struggled with cultural upheavals in their homelands. [While] for Westerners, Buddhism seemed to provide an attractive spiritual alternative to their own seemingly moribund religious traditions. The irony, of course, is that the Buddhism to which these Westerners were drawn was one already transformed by its contact with the West.

And in his book The Scientific Buddha, Donald S. Lopez, Jr., a professor in the Department of Asian languages at the University of Michigan, says: “For the Buddha to be identified as an ancient sage fully attuned to the findings of modern science, it was necessary that he first be transformed into a figure who differed in many ways from the Buddha who has been revered by Buddhists across Asia over the course of many centuries.”

Naturally, religions are a product of their time. And as new cultures come to be, religion shifts to fit their needs and values.

Lopez says: “If an ancient religion like Buddhism has anything to offer science, it is not in the facile confirmation of its findings. . . . [T]he Buddha, the old Buddha, not the Scientific Buddha, presented a radical challenge to the way we see the world, both the world that was seen two millennia ago, and the world that is seen today.”

According to Sharf, the problem is not necessarily that there is old and new, but that their separation may diminish the fundamental value of Buddhism. “In discarding everything that doesn’t fit with our modern view,” he says, “we compromise the tradition’s capacity to critique this modern view.”