by Rabbi Rami Shapiro: This story is rooted in one simple idea: “When you know the truth, the truth will set you free” (John 8:32)…

The truth we are talking about is called perennial wisdom: perennial because it reoccurs in every civilization throughout recorded human history, and wisdom because it reveals the true nature of life and how best to live it. What perennial wisdom frees you from is the illusion of otherness that fuels the sense of fear and alienation that drives so much of our ego-centered lives.

In the context of perennial wisdom, truth is that which leads us beyond alienation and isolation to integration and unity. It is that which leads us beyond fear to love; beyond exploitation of the other to justice for all; beyond violence and war to cooperation and peace; and beyond the zero-sum, winner-take-all worldview of “us against them” to the nonzero, win–win worldview of “all of us together.” In the context of perennial wisdom, truth is that which collapses the divisions between chosen and not chosen, believer and infidel, saved and damned, and leads to the understanding that we are all one community of seekers. Finally, in the context of perennial wisdom, truth is that which transcends the binaries of sacred and profane, heaven and earth, Creator and creation, and allows us to cultivate an awareness wherein we may encounter every mundane, finite, nameable “this” as a manifestation of the infinite, ineffable, and divine That of which we are all a part.

While bearing the stamp of the religion and culture in which any given articulation of perennial wisdom arises, perennial wisdom can be summarized in four points:

All life arises in and is an expression of the nondual Infinite Life that is called by many names: Ultimate Reality, God, Tao, Mother, Allah, YHVH, Dharmakaya, Brahman, and Great Spirit, among others.

You contain two ways of knowing the world: a greater knowing (called Atman, Soul, Self, Spirit, or Mind, along with a host of other names) that intuitively knows each finite life as a unique manifestation of Infinite Life; and a lesser knowing (called self, ego, aham, kibr, and the like) that mistakes uniqueness for separateness and imagines itself apart from rather than a part of Infinite Life.

Awakening the Self and knowing the interconnectedness of all life in the singular Life carries with it a universal ethic calling the awakened to cultivate compassion and justice toward all beings.

Awakening your Self and living this ethic is the highest goal you can set for yourself.

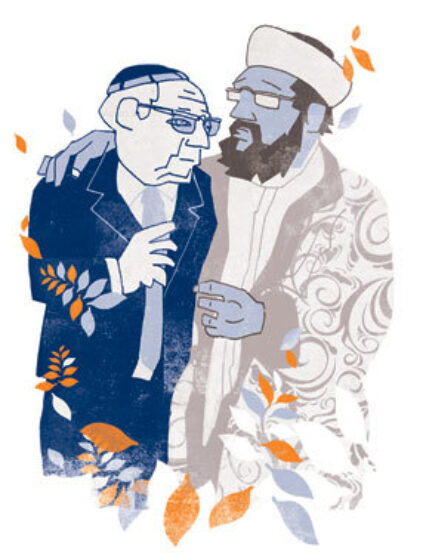

To be clear, we are not advocating a global religion, a single religion to replace the many religions of humankind. We are students of comparative religion and have deep respect for both human religiosity in general and the specific religions that this innate religiosity creates. Yet we see in each specific religion a common thread, which—if highlighted in each faith tradition and held as a central core belief of all humans, religious and otherwise—can provide the foundation for a new civility, if not a new civilization.

Religions Are Like Languages

Some may find it odd that while we claim to respect all religions, we reject the absolutist truth claims of every religion. If a religion isn’t true, why bother with it at all? The answer to this question rests with one’s understanding of religion. While scholars have debated—and continue to debate—just what religion is, we take a softer approach and root our understanding of religion in the metaphor of language.

Like language, religion is a way we humans make meaning out of the raw facts of our existence. It is a human creation reflecting and shaping the civilization from which it comes. Religion, like language, is neither true nor false. It evolves over time, and adapts words and concepts from other religions and languages. Religion, like language, is the way we humans archive and share experience, but it is not synonymous with experience: d-o-g doesn’t bark and g-o-d doesn’t save.

Some religions, like some languages, may be better at expressing some things rather than others, and there may be some things you simply cannot say in a given religion or language but can say in a different religion or language. Just as being born into a mother tongue does not preclude you from speaking other languages, so being born into a specific religion, or no religion, does not preclude you from learning the wisdom of any and all religions. And just as the more languages you know, the more nuanced your understanding of life becomes, so the more religions you know, the more nuanced your understanding of Truth becomes.

Each Religion Speaks to a Facet of Your Experience

Taking our religion–language analogy one step further, just as each language offers its own sense of reality, so each religion offers its own sense of the human condition. And just as your sense of reality is broadened by learning multiple languages, your understanding of the human condition—your condition—is broadened by learning from the world’s religions.

Borrowing from the work of Boston University professor of religion Stephen Prothero and his marvelous introduction to the world’s religions, God Is Not One: The Eight Rival Religions That Run the World, we believe that each religion focuses on one existential problem under which humanity suffers, identifies this problem as the existential problem of humanity, and then sets about to solve it through the unique practices that religion contains. While in no way rejecting Prothero’s position, we expand it a bit.

While we agree that each religion focuses on one existential problem, we suggest that humanity suffers from all of them, though any given human may be inclined to focus on only a few or even only one. Here are the problems, presented in no particular order, proposed by seven classic religions.

Awakening the Self and knowing the interconnectedness of all life in the singular Life carries with it a universal ethic calling the awakened to cultivate compassion and justice toward all beings.

Reality vs. Illusion: Hinduism

According to Hinduism, the existential problem at the heart of the human condition is ignorance of the true nature of reality (avidya) that leaves us living in a world of illusion (maya). This is not to say the world itself is illusory, only that our understanding of it is.

A Hindu parable puts it this way: Imagine you awake in the middle of the night to find a poisonous snake curled at the foot of your bed. Frozen with fear, you spend the night in terror, praying that nothing will cause the snake to strike you and, in so doing, kill you. As dawn rises and sunlight floods your bedroom you realize that the “snake” is, in fact, the belt you neglected to hang up as you prepared for bed the night before. Immediately fear and terror vanish and you achieve moksha, liberation from the illusion of the snake and the fear and terror that the illusion elicited.

The way to liberation is through one or more of the four yogas: service to others (Karma); devotion to God (Bhakti); the study of wisdom (Jnana); and contemplative practice (Raja).

Alienation from God: Judaism

The existential problem that is Judaism’s focus is exile (galut), and the alienation from God that galut entails. Humanity is meant to live in Paradise, the Garden of Eden, as tillers of the soil and midwives to nature’s bounty (Genesis 2:15-16), but we were exiled from the Garden because we ate from the Tree of Knowledge of Good and Evil and fell into the trap of duality. By eating the apple, we consumed the notion that the world is a collection of opposing binaries—good versus bad, us versus them—rather than an integrated network of complementarities—front and back, good and bad, us and them, and all of us together.

The solution to this exile is returning to God (teshuvah) by re-pairing the world with godliness (tikkun). The means for return and repair are the 613 spiritual disciplines (mitzvot) of Jewish practice.

Dissatisfaction by Way of Desire: Buddhism

Buddhism sees the existential problem of humanity as a sense of deep and abiding dissatisfaction with life (called dukkha) caused by addictive desire (trishna). Simply put, we want what we cannot have: permanence, immortality, surety, and security. The more we struggle to attain the unattainable, the more miserable we become, and the more needless suffering we endure.

The solution to dukkha is nirvana, the cessation of addictive desire and the suffering it creates. The way to accomplish this is the Eightfold Path—right understanding of the nature of reality, right thought, right speech, right action, right livelihood, right effort, right mindfulness, and right concentration—which leads to the three essentials of Buddhist life: morality (sila), awakening (samadhi), and wisdom (prajna).

Stained by Sin: Christianity

According to many denominations of Christianity, the existential problem at the heart of the human condition is sin—or more specifically, Original Sin. The Christian insight is that there is something ontologically wrong with us, something we cannot fix on our own.

There is no discipline that will set us right. Only God can fix what is wrong, and indeed God has done so by incarnating as Jesus and dying on the cross as ransom for our sin. Within the context of Christianity—or better, the many Christianities that grow up around this idea—belief in Jesus as Christ and belief in the salvific power of his death and resurrection is the only way to get ourselves right with God.

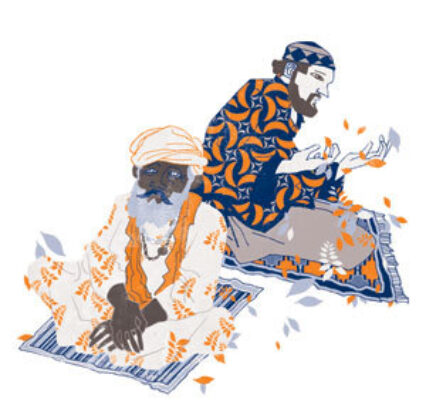

Falling Prey to Pride: Islam

Islam identifies pride as the existential problem that most threatens human flourishing. This is because pride—following the desires of our will rather than submitting to the demands of God’s will (the true meaning of Islam)—keeps us from living the holy life God wishes us to live.

The way of Islam is to submit ourselves to the discipline of the Five Pillars, four of which are revealed in the Hadith of Gabriel, perhaps the most important of all hadiths—reports of the life of the Prophet Muhammad that Muslims consider historical and use as the basis, along with the Qur’an, for the practical and ethical ideals of Islam.

One day while the Prophet Muhammad (Peace Be Upon Him) was sitting in the company of others, the Angel Jibreel (Gabriel) came and asked, “What is Islam?” Muhammed replied, “To worship Allah alone and none other, to pray five times daily, to offer charity according to the law, and to fast during the month of Ramadan” (Sahih al-Bukhari 1:2:48).

To these four, add the fifth, which is mentioned in a separate hadith: making pilgrimage to Mecca at least once during our lifetime, finances permitting.

Adherence to these five pillars helps us overcome pride, place our will secondary to God’s will, and live as God expects and requires.

Losing Touch with Our Heart: Confucianism

For Confucianism, the existential problem we humans face is loss of jen and li. Jen (pronounced ren) translates as human heartedness: our capacity for goodness, generosity, love of neighbor, and care for society. Humans are intrinsically capable of jen because we are born good, but without training in the cultivation of jen we tend to fall into its opposite, selfishness. Li, ritual or propriety, is the way to live our lives and order our society to promote jen. Jen and li together create junzi, the superior person, whose actions are always proper and whose overriding concern is the welfare of others.

The way to cultivate jen and li is the Confucian system of education that focuses on the classics of Chinese literature, and building moral character.

Prisoners of Formality: Taoism

The existential problem highlighted in Taoism is the loss of our intrinsic naturalness. Unlike the Confucian, who believes that our innate goodness needs to be cultivated through formal moral training and literary education, the Taoist holds that we are born free, that goodness arises naturally from living that freedom, and the constraints of formal training and education ensnare us in systems of convention that rob us of our freedom. The solution is to return to the Tao, the way of nature, and to live in harmony with it.

While the Confucian upholds the ideal of the junzi, superior person, the Taoist celebrates the zhenren, the genuine person. To cultivate our innate authenticity, we practice “sitting and forgetting” (ego-erasing meditation, dropping the self, and resting as the Self), “fasting of the mind” (freeing oneself of -isms and ideologies), and “free and easy wandering” (ecstatic journeying in the mountains), all of which foster an alignment with Tao, the way of nature.

While we agree that each religion focuses on one existential problem, we suggest that humanity suffers from all of them, though any given human may be inclined to focus on only a few or even only one.

Mi Problema, Su Problema

Ignorance, illusion, exile, alienation, dissatisfaction, sin, pride, loss of goodness, loss of naturalness and authenticity—are any of these existential problems foreign to you? While it is true that given your personal history, both nature and nurture, genetic and parental, you may see one or more of these problems as being uppermost in your life. Still, if you examine your life carefully enough, chances are you will notice they are all at play and therefore you can learn from all these religions.

This is what spiritual boundary crossers do: They seek out the wisdom in every tradition, religious and otherwise. And this is what we suspect you do as well. Our audience is not those committed to one tradition or another, but rather that growing audience of spiritual boundary crossers who are open to a broader field of spiritual inquiry that embraces the entire spectrum of religion: wisdom seekers who refuse to have their search for Truth limited to the truth claims of any one religion or tribe alone. Instead, they see themselves as heirs to the entirety of human wisdom.