by Ocean Robbins: Salt has long occupied a prominent place in human history. But do you have the all the facts on sodium?

We are proud to announce a new partnership with John and Ocean Robbins and the Food Revolution to bring our readers Summits, Seminars and Masterclasses on health, nutrition and Earth-Conscious living.

Sign Up Today For the Food Revolution Summit Docuseries

For thousands of years, people who didn’t live near the ocean would travel great distances to trade for salt. Salt has been the center of many battles, often referred to as The Salt Wars. And a few British towns that end in “wich” (like Droitwich, Middlewich, Nantwich, Northwich, and Leftwich) were named for and associated with their salt works (the cognate wic sometimes related to salt works, although wic’s usual meaning was “dwelling, place, or town”). Isn’t history neat?

Our esteem for salt goes back to Biblical times. When you call someone “salt of the earth” to indicate that they embody integrity and composure in difficult situations, you’re actually quoting from Matthew 5:13. Salt was valued so highly that it was equated with currency, as you can hear in our modern word “salary,” or “payment in salt.”

But why? What made salt worth journeying, sometimes killing, and occasionally dying for throughout history?

Why We Like Salt So Much

The most basic reason for enjoying salt stems from our biology: the human body requires sodium to perform functions like transmitting nerve impulses, triggering muscles to contract and relax, and regulating fluid balance, albeit in small amounts. Salt is the most readily available and concentrated source of sodium on the planet.

Salt also makes many foods (including some really unhealthy ones) taste better. When a handwritten copy of Kentucky Fried Chicken’s secret recipe of 11 herbs and spices was discovered in the estate of Harlan Sanders’ second wife in 1996, three of the ingredients were salt, celery salt, and garlic salt. (The document also misspelled “oregano,” which should cheer up anyone who struggled in English class and still aspires to entrepreneurial greatness.)

But wait, there’s more. Arguably the most valuable quality of salt has been its ability to preserve food that would otherwise spoil. The word “salad” comes from salt and originally referred to vegetables that were brined and could, therefore, be eaten raw without spoiling or wilting. Throughout history’s famines, droughts, and mass migrations, having a reserve of food that could last for months or even years could mean the difference between survival and death.

The Salty Truth About Salt

So salt is awesome. That means we should be eating lots of it every day, right?

Not so fast. Like many essential nutrients, salt — and sodium — can be harmful in excess. And in the modern world, processing has devalued salt and made it a cheap and ubiquitous additive that saturates our food system. It’s this overuse that gives sodium its bad reputation. Many doctors tell their patients not to add salt to their foods because of the risk of numerous health problems, especially hypertension. And for good reason. One of the most touted sodium facts is that nine out of 10 Americans consume too much of it.

Where Most of Our Sodium Comes From

Where does all that sodium come from? Only about 5% of it comes from salt shakers. Most of the sodium in the American diet comes from processed, packaged, and restaurant foods. But sodium isn’t just added to processed foods because salt tastes good. The real reasons are more troubling. Food manufacturers use salt both to extend the shelf life and to mask the poor taste of low-quality ingredients that allow them to sell their products so inexpensively.

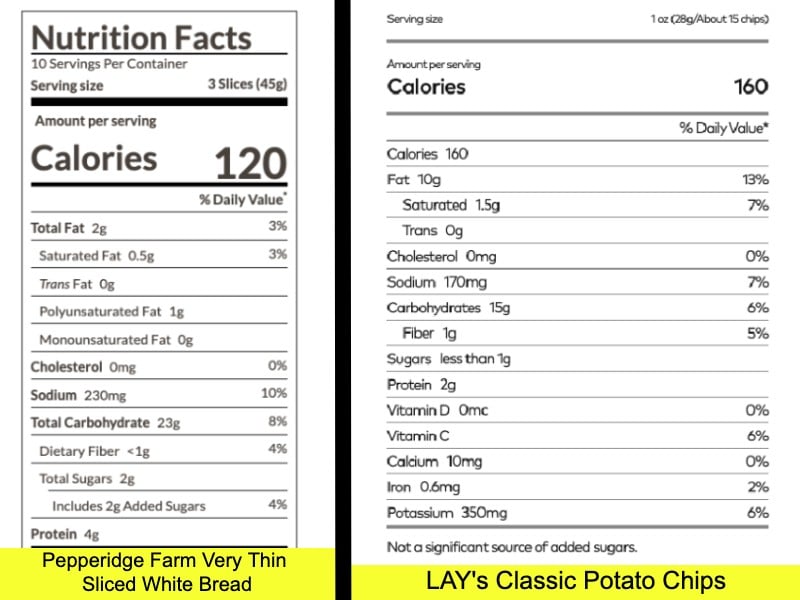

A Sodium Comparison Example

Here’s a quiz: What do you think is saltier, Pepperidge Farm Very Thin Sliced White Bread or LAY’S Classic Potato Chips? That’s a no-brainer, right? Chips usually taste salty, and bread doesn’t. But…

According to their nutritional labels, 120 calories of the bread (three slices) contain 230mg of sodium. While 120 calories of the potato chips serve up about half that amount of sodium (170 mg sodium per 160-calorie serving, to be precise). The reason the chips taste saltier per calorie is that the chips have more calories per gram because they are higher in fat (There are nine calories in a gram of fat, but only four in a gram of carbohydrates or protein). And also because salt is on the outside, readily available to your tongue. The large amount of salt in the bread is baked in and doesn’t taste salty so much as disguise and preserve the not-so-fresh flour, soybean oil, and additives.

Cheese and processed meats also contain loads of sodium. After breads and rolls, the biggest sources of sodium in the American diet are, in order, cold cuts and cured meats, pizza (which is full of cheese), and poultry. Chicken is often injected with salt or brine to increase the water weight and make more money from the same bird.

With all those troubling sodium facts, you’re right to be wary. But sodium itself isn’t necessarily a bad guy, nor is salt if used appropriately. It turns out that the conversation around salt and sodium doesn’t actually need so much polarization when you look at the facts. So let’s separate the sodium facts from fiction.

Difference Between Salt and Sodium

While salt and sodium are often used interchangeably, there’s a difference between the two. Understanding exactly how they differ is important when making decisions about your diet and your health.

What is Salt?

Table salt is a common term for the salt that we add to food or use in cooking, but it isn’t pure sodium. Table salt, or sodium chloride (NaCl), is approximately 40% sodium and 60% chloride by weight.

Most of the world’s salt is harvested from salt mines (from sea beds that dried up long ago) or by evaporating seawater and other mineral-rich waters. Salt has various purposes, the most common being to flavor foods. Salt is also used as a food preservative since bacteria have trouble growing in a salt-rich environment. As we’ve seen, flavoring and preservation are the two main reasons manufacturers add sodium chloride to fast food items and many packaged foods.

4 Types of Salt and How They Differ

There are several varieties of salt, some of which you may have seen at your grocery store or specialty market. The main categories include:

Table Salt

Table salt usually contains added iodine, an essential mineral that helps prevent hypothyroidism and other health problems that result from an iodine-deficient diet. (Iodine is an important mineral. And ⅓ of the human population is at risk for deficiency. You only need about 150 mcg per day — and for many people, iodized salt meets that need. But if you don’t eat iodized salt, then it’s wise to make sure you have another healthy source like seaweed.) Most of us are familiar with table salt as the shaker that sits next to the pepper on restaurant tables — and often in our own dining rooms. These salt granules are small enough to fit through a shaker without clogging it. Some table salt is coated with an anti-caking agent (deemed Generally Recognized As Safe, or GRAS, by the USDA, if present below a certain threshold) to prevent the particles from clumping together.

Sea Salt

Sea salt comes from evaporated ocean water. It has become more popular in recent years, partly because of marketing that makes it seem more “natural.” Sea salt granules are larger, coarser, and less refined than table salt. And it often contains more minerals that naturally come from the ocean, such as potassium, iron, and zinc. While most sea salt doesn’t naturally contain iodine, many brands now also add this important mineral. However, sea salt can also contain microplastic residues because of their increasing prevalence in the ocean.

Himalayan Pink Salt

Himalayan pink salt is coarse and chunky like sea salt and comes from mines in Pakistan. It’s known for its pinkish hue. This type of salt contains small amounts of calcium, iron, potassium, and magnesium, making it slightly lower in sodium than regular table salt. However, while some people eat pink salt for the minerals, they’re present only in small quantities. You’re probably better off getting most of your minerals from your food. There are also some environmental concerns with using Himalayan Pink Salt. It’s a non-renewable, finite resource that requires many greenhouse gas-emitting food miles to reach global consumers.

Kosher Salt

Kosher salt is most often used in Kosher Jewish cooking. It gets its name from the texture and larger size of its flakes, making it ideal for removing moisture from meat cooked in the koshering process. Kosher salt doesn’t usually contain iodine and is less likely to contain additives like anti-caking agents.

Which Salt is Best?

Which salt is best is up to your individual tastes, preferences in texture, how and what types of dishes in which you like to use salt, and whether you want to add some iodine to your diet. The main benefit of choosing salts that are less processed is that you avoid additives and anti-caking agents in some regular table salts.

Sodium Facts: What Is Sodium?

Now that we’ve covered salt, how is it different from sodium? Let’s go over some of the top sodium facts.

Sodium is a naturally-occurring mineral that is either innately found in foods, added during the manufacturing process, or sometimes both. It’s an electrolyte, which means it carries an electric charge when dissolved in bodily fluids such as blood. Approximately 90% of the sodium we eat is in the form of sodium chloride. The other 10% comes from other forms of sodium in foods we eat, like baking soda, also known as sodium bicarbonate.

Most of the sodium in your body is in your blood as well as the fluid around your cells. Sodium plays a key role in maintaining normal nerve and muscle function as well as keeping bodily fluids in normal balance. Your body gets sodium through eating and drinking and eliminates it primarily through urine and sweat losses — a process managed by healthy kidneys. When the sodium you eat and the sodium you excrete aren’t in balance, this affects the total amount of sodium in your body, which can lead to health problems.

What Happens When You Don’t Have Enough Sodium In Your Blood

Not having enough sodium in your blood can cause a condition called hyponatremia. It is generally defined as a sodium concentration of less than 135 mEq/L of blood, with severe hyponatremia being below 120 mEq/L. Hyponatremia happens when your body holds onto too much water, which dilutes the amount of sodium in your blood and causes low levels.

There are more than three million cases of hyponatremia per year in the United States. Symptoms can include nausea, headache, confusion, and fatigue. In the most severe cases, it can cause seizures, coma, or even death.

Causes of Hyponatremia

While consuming too little sodium can theoretically be a cause of hyponatremia, it rarely is. According to the Mayo Clinic, the most common causes are:

- Certain medications, especially diuretics, antidepressants, and pain medications that can interfere with the normal hormonal and kidney processes that keep sodium concentrations within the healthy, normal range.

- Heart, kidney, and liver problems. Congestive heart failure and certain diseases affecting the kidneys or liver can cause fluids to accumulate in your body, which dilutes the sodium in your body, lowering the overall level.

- Chronic, severe vomiting or diarrhea and other causes of dehydration.

- Drinking too much water, which can cause low sodium by overwhelming the kidneys’ ability to excrete water. Because you lose sodium through sweat, drinking too much water during endurance activities, such as marathons and triathlons, can also dilute the sodium content of your blood. In one study, 13% of Boston Marathon finishers were hyponatremic at the end of the race.

- Adrenal gland insufficiency (Addison’s disease) can affect your adrenal glands’ ability to produce hormones that help maintain your body’s balance of sodium, potassium, and water. Low levels of thyroid hormone also can cause a low blood sodium level.

How Much Sodium Do You Need?

Hyponatremia is a condition you should be aware of. But unless you have certain specific medical conditions, or drink copious amounts of water, it’s probably not a reason to eat large amounts of sodium. The Dietary Guidelines for Americans recommend for the average healthy adult to get less than 2,300 mg of sodium per day (that’s less than one teaspoon). The American Heart Association and the Institute of Medicine recommend that most adults should consume 1,500 mg per day. Your optimal sodium intake can vary depending on individual factors like gender, age, ethnicity, overall health, and existing medical conditions, but this gives a good reference range for most people.

Most fruits and vegetables contain modest amounts of sodium. And it’s entirely possible you can get enough just from your food, without adding any salt at all. Or you can add a little bit, and do just fine. If you’re on a low or no added salt diet, and you’re concerned, you might want to ask your health care provider to check your sodium blood levels to make sure they’re in the normal range.

What Happens When You Get Too Much Sodium?

While hyponatremia is a concern for some, the far bigger problem, for most people, is getting too much sodium. Worldwide, the average person is consuming 3,950 mg of sodium per day, or roughly double the recommended amount, which brings us to the problems that come with too much sodium. And the biggest one is heart disease.

Heart Disease

Too much sodium in your body can raise your blood pressure, as excessive sodium intake can make it difficult for your kidneys to remove fluid. High blood pressure, or hypertension, is a risk factor for heart disease because it can enlarge the heart’s left pumping chamber and weaken the muscle, damage artery walls, and increase risk for plaque buildup that may cause heart attack or stroke. A 2014 study published in the New England Journal of Medicine estimated that worldwide, excessive sodium consumption caused 1.65 million heart disease deaths per year. That’s 4,500 deaths every single day.

Kidney Disease

Having high blood pressure also puts stress on the important filtering units of your kidneys. This can lead to scarring, which lessens the ability of your kidneys to regulate fluid balance, further increasing blood pressure. As you can imagine, this can become a vicious cycle, leading to kidney disease and even kidney failure. Kidney disease can be difficult to detect, so many people don’t even know they have it.

Type 2 Diabetes

How well your body regulates blood sugar can also be impacted by extra sodium in your body. High sodium can worsen insulin resistance, increasing your risk of developing type 2 diabetes.

Researchers recently evaluated the relationship between sodium intake and diabetes risk in a Swedish population study of 2,800 people. The study participants were divided into groups based on levels of sodium consumption. People with the highest sodium consumption (over 3.15 grams per day) had a 58% higher risk of developing type 2 diabetes compared with the group that had the lowest consumption (under 2.4 grams per day).

The Potassium-Sodium Balance

Potassium and sodium are both electrolytes that are needed for your body to function normally. They work together in harmony, And the balance between them is important. But most people in the modern world are not only eating too much sodium, but they’re also eating too little potassium, which exacerbates the problem. The combination of consuming more sodium and having too little potassium in your diet is associated with higher blood pressure and increased risk of cardiovascular disease.

Reducing sodium and increasing potassium in your diet can help control hypertension and lower your risk of cardiovascular disease and death. Rich sources of potassium include avocados, sweet potatoes, spinach, watermelon, coconut water, white beans, edamame, and, perhaps, the most famous potassium source of all, bananas.

Which Foods Are High in Sodium?

Sodium is abundant in much of our modern food system. A typical 14” pizza contains 5,101 grams of it — more than double the recommended daily amount from all sources!

The best thing you can do to limit your sodium intake is to avoid fast and processed foods as much as possible, eating a whole foods, plant-based diet instead.

Reading nutrition labels is also a good habit to practice, so you can understand just how much sodium is in one serving of a food. Then, you can determine whether it can fit healthfully into your day. A food can carry the “low-sodium” label if it contains 140 mg or less per serving. It’s considered “very low in sodium” if it contains 35 mg or less per serving. And for a “sodium-free” label, the food must contain 5 mg or less per serving.

Foods to Watch Out For

When you order carry-out or eat at a restaurant, the terminology used in the descriptions on the menu can indicate that an item is high in sodium. Look for words like brine, cured, broth, au jus, miso, pickled, smoked, teriyaki sauce, and soy sauce as clues that there is a lot of sodium in a dish.

Some of the most high-sodium foods tend to include:

- Cheese

- Processed or seasoned meat products

- Fast food

- Frozen dinners & other packaged foods

- Canned soups

- Condiments and sauces

- Store-bought salad dressings

- Fermented foods like kimchi, miso, and sauerkraut (though you may want to use these as a source of salt since they offer so many other health benefits)

Kid’s meals and foods marketed to children are especially problematic. Surveys show that approximately 90% of kids in the United States eat too much sodium. When it comes to typical “kid” foods, the American Heart Association says that the most salt-heavy foods consumed among children ages 6-18 years old include pizza, burritos and tacos, sandwiches, breads and rolls, cold cuts and cured meats, and canned soups.

Naturally Low-Sodium Foods

Fruits and vegetables are among the best low-sodium foods. Plus, they’re full of nutrients and taste great.

Some examples of fruits and vegetables that contain naturally-occurring sodium, but are still low-sodium include:

- Sweet Potatoes

- Broccoli

- Cauliflower

- Celery

- Carrots

- Beets

- Spinach

- Artichokes

- Cantaloupes

- Bell Peppers

- Berries

- Mushrooms

To many people, unsalted foods taste bland at first. It can take a bit of time for your palate to adjust to unsalted foods if you’ve been used to eating salty, processed foods for a prolonged period. But the good news is that your taste buds will change and recalibrate if you give them a chance. If you use less salt, you will eventually taste it more. And foods that once tasted normal will come to taste terribly over-salted.

Instead of salt, experiment with other spices and herbs to add flavor to your food. In addition to salt-free seasonings, you may find that using garlic and onion powder, Italian seasonings, curries, turmeric, or cumin hit the spot for various dishes. There’s no need for boring meals. Life is too short to eat boring food!

Low-Sodium Recipes

Salt-free cooking is easier than you might think, especially when you’re working with flavorful ingredients to begin with. These recipes are perfect examples of that!

Balsamic Dijon Hemp Vinaigrette

Many store-bought salad dressings come with a lot of added sodium. This lower-sodium dressing gets a bit of salty and umami flavor from the organic miso, some tang from the balsamic vinegar, and creaminess from the hemp seeds. Enjoy it on salads or grain bowls!

Toasted Cumin Lemon Carrots

The beauty of using less salt is that you’ll start to notice the true flavors of foods. While the cumin, carrots, and lemon complement each other perfectly, the simplicity of this dish also lets each of the ingredients shine on their own. Add some fresh herbs like parsley, dill, or cilantro for extra flavor and a nutrition boost.

Lentil Stuffed Sweet Potato with Tahini Lemon Sauce

No salt needed when you have a (naturally) sweet potato, some pungency from the onions, and plenty of delicious (and healing!) spices. Top with a creamy tahini lemon sauce, and you’ve got the perfect meal that has natural sodium without any added salt.

Should You Eat Salt?

Sodium is an important part of a healthy diet. But too little and especially too much can damage your health. Adding salt while cooking or shaking it on food isn’t necessary for most people because so many foods already contain it. And most people are already consuming way too much sodium, to begin with. Cut down on processed and fast foods and increase your intake of whole plant foods to keep your sodium levels in check. If you use salt when cooking, determine which type best fits your needs and preferences. And experiment with salt-free seasonings to enhance flavor. If you don’t use salt fortified with iodine, make sure you have another source of it — such as sea vegetables — or that you take an iodine supplement.