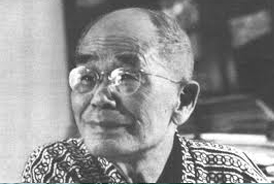

by Daisetz Teitaro Suzuki: Those of you who are accustomed to listening to the usual explanations of Pure Land Buddhism may find my lectures on this subject unusual and unorthodox, but I am willing to take that criticism.

Ordinarily speaking, Pure Land doctrine

is heavily laden with all kinds of what I call “accretions,” which are not altogether necessary in order for modern people to get at the gist of the teaching.

For instance, Amida is the principal subject of Pure Land Buddhism. He

is represented as being so many feet in height and endowed with the excellent

physical features of a great man; he emits beams of light from his body, illuminating the world—not just one world, but many worlds, defying human calculation or measurement; and on every ray of light that comes out of his body, in fact, from every pore of his skin, there are so many Buddha-lands, decorated in a most extravagant manner. The descriptions almost exceed the imagination.

Of course this too is the product of man’s mind, so I cannot really say it is

beyond human imagination. But we can see how the Indian mind, more than any

other, is richly endowed with the ability to create imagery. When you read the

sūtras and listen to the old ways of explaining Pure Land doctrine, you will be

surprised at how differently those people viewed such things, when compared

with our modern way of thinking.

I am not going to touch upon these traditional aspects of the doctrine, so I

am afraid my own explanations will be somewhat prosaic, devoid of the usual

glamour and rich imagery. In a way, it will be Amida religion brought down to

earth; but at the same time the doctrine is not to be treated from the intellectual

point of view, on the relative plane of thought. It is after all altogether beyond

human intellection.

The Pure Land and Amida are revealed on this earth, though not as is taught

by orthodox preachers. The Pure Land is not many millions and millions of

miles away to the west. According to my explanation, the Pure Land is right

here. Those who have eyes to see it can see it right here, even in this very hall.

Amida is not presiding over a Pure Land beyond our reach. His Pure Land is this

dirty earth itself. When I explain things in this way I am going directly against

the traditional or conventional Pure Land doctrine. However, I have my own

explanations and interpretations, and perhaps after these lectures are over you

will agree with them, though of that I cannot be quite sure!

A Japanese Shin Buddhist friend of mine in Brazil recently wrote to me,

requesting that I write out the essential teachings of the Pure Land school in

English for the Buddhists there, because they found it difficult to translate such

things from Japanese into Portuguese. He wanted me to present it so as to make

Amida and Pure Land doctrine appear somewhat similar to Christianity, at least

superficially, and yet to retain characteristic features of the Pure Land doctrine.

So I sent the following to him. Whether he agreed with my views or not, I do not

know. You might say I wrote it for my own edification.

First: We believe in Amida Butsu, Amitabha Buddha, as Savior of all beings.

(“Savior” is not a word often used among Buddhists; it is a kind of condescen

sion to the Christian way of thinking.) This Amida Buddha is eternal life and in

finite light. And all beings are born in sin and laden with sin. (This idea of sin is

to be specially interpreted to give it a Buddhist color, which I will do later on.)

Second: We believe in Amida Buddha as our Oya-sama. (Sometimes the

more familiar “Oya-san” is used in place of “Oya-sama,” but the latter is more

generally used. Oya-sama, in this context, means love or compassion. Strictly

speaking, there is no word corresponding to Oya-sama in English or any Euro

pean languages. Oya means parent, and -sama is an honorifi c suffix. Oya can

mean either father or mother, and can also mean both of them; not separately,

but mother and father as one. Motherly qualities and fatherly qualities are united

in Oya. In Christianity God is addressed as Father: “Our father which art in

Heaven.” But Oya-sama is not in heaven, nor is Oya-sama the Father. Oya-sama

is neither a “he” nor a “she.” I don’t like to say “it,” so I am at a loss what to say.

Oya-sama is such a peculiar word, so endearing and at the same time so full of

religious significance.)

Third: We believe that salvation (“salvation” is not a good word here, but I

am trying to comply with my friend’s request) consists in pronouncing the name

of Amida in sincerity and with devotion. (This pronouncing the name of Amida

may not be considered so important, but names have certain magical powers.

When a name is uttered, the object bearing that name is conjured up.)

In The Arabian Nights’ Entertainments, when the devil’s name is pro

nounced, the devil appears. Among some primitive peoples, the name of the su

preme being is kept a secret. It is revealed only to those who have gone through

certain rituals. The initiate is led by one of the elders of the religion into a dense

forest where there is no danger of being overheard by anybody. Then the elder

reveals the name to him. By knowing the name, the initiate is now fully qualified

as a leader himself. The name plays an important role in religious life.

Amida’s name is pronounced in sincerity and with devotion. The formula is

Namu-amida-butsu. Butsu is Buddha, namu means “I take refuge”: I take refuge

in Amida Buddha. Or we may take namu as meaning adoration to Amida Bud

dha. It is a simple formula. There is nothing especially mysterious about it, and

you may wonder how this name or phrase could have such wonderful power.

Now I have to say something about hongan. Hongan, according to my inter

pretation, is the primal will. This primal will is at the foundation of all reality.

Hongan as expressed in the Sūtra of Eternal Life consists of 48 different vows,

but all 48 may be summarized in one basic vow, or hongan, which is: Amida

wants to save all beings. Amida desires to have all beings brought over to his

land, which is the land of purity and bliss. And those who earnestly, sincerely,

and devotedly believe in Amida, will all be born in the Pure Land.

This birth does not take place after what is called death. To sincere followers

of the Pure Land, instead of being born in the Pure Land, the Pure Land itself

is created or comes into existence when we sincerely pronounce Namu-amida

butsu. Therefore, instead of going over to the Pure Land, the Pure Land comes

to us. In a way, we are carrying the Pure Land within us all along, and when we

pronounce that magic formula Namu-amida-butsu, we become conscious of the

presence of the Pure Land around us, or rather, in us.

The hon of hongan means original or primal, and gan is generally trans

lated “vow.” But I have misgivings about using vow as an equivalent for gan.

Sometimes it is translated “prayer.” Gan means literally “wish” or “desire.”

Philosophically speaking, it may be better to say “will,” so that hongan would

be rendered “primal will.” Why gan cannot properly be translated as “vow,”

“prayer,” “wish,” or “desire” will become clearer later. I am just trying to give

you an idea now of how I interpret some of these terms.

I wrote a little book called A Miscellany on the Shin Teaching of Buddhism

which was published in Japan in 1949. It contains rather fragmentary explana

tions of the Shin teaching, but parts of it may be helpful in gaining a general

view of Shin Pure Land Buddhism.

The Pure Land teaching originated in China, but it reached its full develop

ment in the Japanese Shin school of Pure Land Buddhism. The Shin school is the

culmination of Pure Land thought, and that culmination took place in Japan. The

Japanese may not have very many original ideas to contribute to world thought

or world culture, but in Shin we find one major contribution Japanese can make

to the outside world. There is one other major Buddhist school that developed in

Japan, the Nichiren sect. But all the other schools more or less trace their origin

as well as their form either to China or to India. Nichiren is more or less related

to the nationalistic spirit of Japan and is often confused with nationalism. But

Shin is absolutely free of such connections; in that respect, Shin is remarkable.

Shinran, the founder of the Shin sect, was born in Kyoto about eight hundred

years ago. He is generally made out to be of noble lineage, but that I suspect is

fiction. His family was probably relatively cultured and may well have belonged

to the higher levels of society, but their connection, if any, to the aristocracy

was I think remote. In any case, his real religious development took place when

he was exiled to the country, far from the capital, the center of culture in those

days. He was a follower of Hōnen, founder of the Pure Land (Jōdo) school in

Japan. Hōnen’s influence was very great at the time, and priests belonging to

the older established schools did not like that. Somehow they contrived to have

Hōnen banished to Tosa, then a remote area of the country. Shinran was also

exiled, to the northern part of Japan. His decisive religious experience really

took place during this exile, while he was living among the common people. He

understood well their spiritual needs. In those days Buddhism was somewhat

aristocratic, and the study of Buddhism was mainly confined to the learned few,

who were rather addicted to learning. But Shinran knew that mere learning was

not the way to religious experience. There had to be a more direct way that did

not require the medium of learning or ritual. In fact, to experience a full awak

ening of the religious consciousness, all such things must first be cast aside.

Such mediums would only interfere with our attempts to directly attain this full

awakening, which is the consummation of the religious life. Shinran came to

realize this himself, and he finally found the most direct way to the attainment

of this awakening.

Let me read a bit now from A Miscellany on the Shin Teaching:

Of all the developments Mahayana Buddhism has achieved in the Far East, the

most remarkable one is the Shin teaching of the Pure Land school. It is remarkable,

according to my judgment, chiefly for the reason that geographically its birthplace

is Japan and historically it is the latest and highest evolution the Pure Land teaching

could have reached. The Pure Land idea originated in India (because the sūtras used

by this sect were originally compiled in India, the ideas must have developed fi rst in

India) and the sūtras devoted to its exposition were compiled probably about three

hundred years after Buddha (that is, about one or two centuries before the Christian

era). The school bearing its name, however, started in China towards the end of the

fifth century when the White Lotus Society was organized by Hui-yüan (334-416) and

his friends in 403. The idea of a Buddha-land which is presided over by a Buddha is

probably as old as Buddhism, but a school based upon the desire to be born in such a

land in order to attain the final end of the Buddhist life, did not fully materialize until

Buddhism began to flourish in China as a practical religion. It took the Japanese genius

of the thirteenth century to mature it further into the teaching of the Shin school. Some

may wonder how the Mahayana could have expanded into the doctrine of Pure Land

faith, which apparently stands in direct contradiction to the Buddha’s supposedly

original teaching of self-reliance and enlightenment by means of prajñā.

[Dr. Suzuki explains the following Shin terms at the blackboard]

Amida is standing on one side, and on the other side is bombu (or bompu), the

ordinary people, just as we all are. We sometimes see this term rendered as “all

beings” in English. Amida Buddha is the hō (Dharma), and we bombu are ki.

Hō and ki are difficult terms to translate. Hō is on the other side and ki is on this

side. Religious teachings start from the relationship between them. Hō might be

considered as corresponding to God or Christ, and ki is this sinful person. Hō

is the o

ther-power, and ki is self-power. Other-power and self-power stand in

contrast; and in order to be born in the Pure Land, self-power is to be altogether

abandoned and other-power embraced. In fact, when self-power is embraced

by other-power, self-power turns into other-power; or, other-power “takes up”

self-power altogether.

Or again, on one side we have the Pure Land, and on the other side this world.

“This world” is more commonly called shaba in Japanese and Chinese—it is a

Sanskrit term originally. The other world is called Jōdo. (Jō means pure, do is

land, or “Pure Land.”) Shaba is, we might say, the land of defilement. So there is

Jōdo, the land of purity, or the Pure Land, and shaba, the defiled land. The Pure

Land is the realm of the absolute, and shaba the realm of relativity.

When we pronounce Namu-amida-butsu, Amida is on one side and namu is

on the other. Namu represents self-power or ki; Amida is hō, the other-power.

Namu-amida-butsu symbolizes the unifi cation of ki and hō, Amida and bompu,

self-power and other-power, shaba and Pure Land—they are unifi ed, identified.

So when Namu-amida-butsu is pronounced, it represents or symbolizes the uni

fication of the two. “Unification” is not an adequate term, but its meaning will

hopefully become clearer.

Now Amida is on the other side, the bompu is on this side, and shaba is

where we are. The Pure Land reveals itself when we realize what we are, or,

what Amida is. Other-power is very much emphasized in Shin teaching. When

Amida and other-power are understood, the Pure Land will be understood too.

When Amida’s essential quality is understood, hongan and compassion, or love,

also become known. It is just like holding a cloth at the central part; if you pull

the middle up, all the rest comes with it.

In giving names to objects we commonly fall into the error of thinking that the

names stand for the actual objects themselves. This is a danger that is always

present in name-giving, but we cannot on that account disregard the importance

of names. Names represent a form of discrimination; they help us distinguish

one thing from another, and this enables us to know their nature to some extent.

Without a name, an object could not be distinguished from other objects. Distin

guishing or discriminating helps us in this way to understand the objects around

us. But names are not everything.

Man is also distinguished from other beings in that he is a toolmaker. Names

are also a sort of tool; we can put them to use to better deal with the objects

around us. But there is also a tyranny of tools. We make and surround ourselves

with tools of all kinds, whereupon the tools begin to tyrannize us. Instead of us

using them, they turn against their inventor. We become the tools of the tools

we make.

This situation is especially noticeable in modern life. We invent machines,

and they in turn control human affairs. Machines, especially in recent years,

have inextricably entered our lives. We now must try to adjust ourselves to ma

chines, for once they are out of our hands they refuse to obey our will.

In our intellectual endeavors, our ideas can be despotic too. We cannot al

ways be in control of ideas. We invent or construct ideas and concepts to make

life more convenient. Then these very ideas which we intended to be so con

venient become unmanageable and control the inventors themselves. Scholars

invent ideas and then forget that they invented them in order to deal with certain

realities. For instance, each of the branches of science, whether it is called biol

ogy, psychology, or astronomy, has its own premises, its own hypotheses. Each

branch organizes the fields it has chosen—stars, animals, fish, and so on—and

deals with those realities according to the special concepts its scientists have

invented to enable them to handle the subjects of their research. Whatever situ

ation comes along in the pursuit of their research or exercise of their ideas that

does not happen to be amenable to those ideas, they drop. Instead of dropping

the ideas and trying to create new ones in order to overcome the unexpected dif

ficulties that arise, they stick to the old ideas they invented and try to make the

new realities fit the old concepts. Or else they simply exclude those things which

cannot easily be worked into the network of ideas they have invented.

I have heard that some scientists have themselves compared their methods

to catching fish in a net with standardized meshes; those fish which fail to be

scooped up in the net will be dropped and unaccounted for. They just take up

those that can be caught in their net and try to explain their catch by means of

their ready-made ideas. The fish that remain uncaught are treated as if they did

not even exist. “These exist,” say the scientists of those that have been caught in

the net. All the other fish are nonexistent.

The same can be said of astronomy. Those stars which do not come within

the scope of the telescope are usually neglected. Yet more powerful telescopes

are developed to enable the astronomers to make more extensive and deeper

surveys of the heavens. But when asked about the parts of space that lie beyond

the scope of their present telescopes, they tend to disregard the question. Some

times they go as far as to say that space is empty beyond a certain group of stars.

Certain galaxies make up their astronomical maps, and beyond those, they say,

there is a void.

But such conclusions are altogether unwarranted. If scientists would limit

their conclusions to what they could survey or measure, and admitted that they

did not know beyond that, and did not venture any theory or any hypothesis,

that would be all right. But blinded by their success within these boundaries,

they try to extend that success beyond them, as if they had already surveyed and

measured those unknown parts. Most scientists make this mistake, and, unfortu

nately, people tend to rely on what the scientists say.

To be truly scientific, they must always qualify their statements, because they

always start from certain established hypotheses. Formerly scientists couldn’t

explain light, so they invented what they called “wave theory.” But wave theory

did not account for all the phenomena connected with light, so they then came

up with what they called “quantum theory,” which made explanations of certain

other phenomena possible. But later they came to discover that to explain all the

phenomena, they had to use both theories. The trouble with that, I am told, is

that the two hypotheses contradict each other. If the wave theory is adopted, the

quantum theory must be thrown out; if the quantum theory is taken up, the wave

theory must be discarded. Yet the phenomena themselves exist, and scientists

cannot deny their reality. So however contradictory it is on a logical plane, they

have to adopt both theories, and somehow make them compatible.

All our surveys of reality are accomplished by means of our five senses. If

we possessed another sense, or two or three more senses, besides the fi ve we

already have, then we might perceive an altogether different universe.

To say that what we experience via our five senses exhausts reality is a to

tally unfounded presumption on our part. We can say that within the limits of

our five senses and intellect the world is understood so, explained so, interpreted

so. But there is no way to deny the existence of something (though it may not

be proper to call it a “thing”) higher, deeper, and more pervasive which may lie

beyond the ken of our five senses and intellect. If we do have some such extra

sense within us, even though it is largely undeveloped—and some people do

claim to have that kind of sense or faculty—then we may have another way of

coming in contact with reality that is deeper and more extensive than our ordi

nary sensory and intellectual experience. It would be arrogant for someone to

deny the existence of a higher and deeper “intuition,” and declare, “Nothing can

exist outside my sensory or intellectual perceptions.”

Now let me write the six Chinese characters “Na-mu-a-mi-da-butsu” on the

blackboard. This is called the Nembutsu and is the cornerstone of the entire Pure

Land teaching. Namu-amida-butsu is also known as the Myōgō, or Name of

Amida Buddha, although it contains something more than the Myōgō itself. The

efficacy of the Myōgō enables us to be born in Amida’s Pure Land, to realize the

highest reality, and fully grasp the ultimate truth. Myōgō does not work on the

level of our senses and intellect, which are relative; it works on the part of our

mind or being that lies beyond the senses and intellect. Those who are addicted

to intellection would probably deny the efficacy of the Myōgō to explore those

fields of human being which are beyond and cannot be surveyed by intellection,

and deny as well the existence of such fields.

In religious life there is a phenomenon that we call “faith.” Faith is a strange

and wonderful thing. Ordinarily, we speak of “faith,” or “belief,” in a context of

something beyond our ordinary comprehension that cannot be certified by our

ordinary knowledge. Yet in religious faith there is something more to be consid

ered. We have to venture into the life that is opened up by faith.

In the relative sense of faith, the one we use in ordinary life, we can say, “I

cannot believe it unless I have seen it or heard it personally.” We may neverthe

less believe something not by means of direct personal experience but through

the communication of our friends or books. And if we judge the basis of that

belief to be strong and verifiable enough, we will accept it as true, even if the

proof lies outside of our direct personal experience.

But in religious belief there is something more. Even if our intellect is un

able to verify it objectively or scientifically, there is something in religious faith

which somehow compels us to accept it as reality. Though we may not have

experienced it, it still almost demands our acceptance, whether we will or not.

Theologians talk about “accepting faith” as a kind of perilous decision we have

to make. It is a venturesome deed or experience, a plunging into an unknown

region and deciding to risk our faith and destiny.

I am afraid that people who accept such a theology are still on the plane of

relativity. The fact is, we are compelled—there is no choice—to accept faith. All

religions contain a similar element. Instead of Amida being taken into our life or

being, we are carried away by Amida. This is how the Myōgō starts to live and

become actual life within Shin devotees. Some people ask about the significance

of the Myōgō and how it could possibly be so efficacious as to take us to Amida

and make us be born in the Land of Purity. As long as a person has such doubt

or suspicion or hesitancy in accepting the Myōgō in true faith, then he or she is

not yet within its working.

The Indian sūtras tell of a mythical golden-winged bird of enormous size

that eats dragons for its food. The dragons live deep in the ocean, but when the

golden-winged bird soaring high above detects the dragons down at the bottom

of the ocean, it sweeps down from the sky; the waves open up and it picks the

dragons out of the deep and eats them. Of course the dragons are afraid of the

approach of the bird and dread becoming its meal.

Someone once asked a Buddhist teacher, “What does the bird who has bro

ken through the net eat?” The mythical bird who has broken through the net is

perfectly free, absolute master of itself. We ourselves are caught up in various

kinds of nets, mostly of our own making. They may not really exist, but we

imagine ourselves caught in them. This bird—that is, one of us who has been

spiritually enlightened—is one who has broken through all the nets and now

enjoys perfect freedom. Now the question to the Buddhist teacher, “What food

does such a bird eat?” is the same as asking, What kind of life does an enlight

ened man, one who is spiritually free, lead? Or, What kind of life would a person

lead who believes totally in the Myōgō and is possessed by Amida. What kind

of person would he be?

Most people ask questions of this kind as if the question had nothing to do

with them at all. What is the use of trying to know about such matters, when we

should instead be such a person ourselves. But that is how we are made; this cu

riosity is a frailty of human nature. At the same time, this is what makes our lives

distinguishable from those of the other animals—they don’t ask these questions.

The master then said: “Come through the net yourself. Then I will tell you.”

Once through the net, no telling is needed. He will know for himself. Instead of

asking idle questions about the life of the spiritually free, why not free yourself

and see for yourself what kind of life it is? The same can be said of questions

about the life of a Shin devotee. Americans sometimes ask me what significance

the message of Buddhism has for our modern life. We may explain the kinds

of benefits, advantages, material or otherwise, which come, for example, from

belief in the Myōgō. But instead of being informed by someone else about the

advantages that might accrue from accepting the Myōgō, they should just ac

cept the Myōgō; and try … no, not try, just live it. Then they will know what it

means.

This is what distinguishes religious life from relative, worldly life. In the

relative life we want to know beforehand all that may result from our doing

this or that; then we proceed to take action expecting a certain outcome. But

religious life consists in accepting and knowing, and at the same time living that

which is beyond knowledge. So in knowing and living, living is knowledge, and

knowing is living. This kind of difference sharply distinguishes the religious

from the worldly life. In actual fact there is no such thing as spiritual life distin

guished from worldly life. Worldly life is spiritual life, and vice versa. It is just

that we become blinded and confused in our encounters with the world. Just as

scientists are caught in the nets they weave for themselves, we too, in taking all

our inventions for realities, are blinded by them. We have to fight these unreali

ties. Actually, to call them unrealities is not exactly correct, for they are, with

reservations, real enough. That is something we frequently fail to recognize or

acknowledge.

Now regarding the Myōgō, Shinran, the founder of the Shin sect, says, “One

pronouncing of the Myōgō is enough to make you be born in the Pure Land.”

Birth in the Pure Land is not an event that happens after death, as is popularly

assumed. It takes place as we are living this life.

I was reading a Christian book recently in which the author speaks about

Christ being born in the soul. We generally think Christ was born on a certain

date in history, at a certain place on earth. This occurred not in the usual biologi

cal way but through the miraculous power of God.

But this Christian author says that Christ is born in our soul. And when that

birth is recognized, when we become conscious of Christ’s birth in our soul,

that is when we are saved. So Christ is born in the course of history, but that

historical event takes place in our own spiritual life. Christ is born, and we must

become conscious of his birth in us. He is not born just anywhere, but in us,

every day, at every moment; not once in history, but repeatedly, everywhere, at

every moment.

And according to this author, his birth is dependent on our dying to our

selves. We must die to what we call the ego. When the ego is altogether forsaken

and the soul is no more disturbed, there will be no anxiety, annoyance, or wor

ries whatever, for all worries come from being addicted to the idea of the self.

Therefore, when the self is completely given up, all the disturbances are quieted,

and absolute peace prevails in the soul, which, he says, is “silence.”

It is remarkable to see this Christian writer speak of silence. When silence

prevails in the soul, that is the moment Christ is born in our soul. So silence is

needed. When everything is kept in silence, that is the time, the opportunity, for

spiritual being to enter our soul. Silence is attained when the self is given up;

when the self is given up, the consciousness of dualistic thoughts is altogether

nullified; that is to say, no dualism exists.

When I say dualism does not exist I do not mean that duality itself is anni

hilated. While the duality remains, an identification takes place; the two are left

as two, and yet there is a state of identity. That is the moment silence prevails.

When there are two (“two” means more than two, that is, multiplicity), noise of

various kinds usually results, a disturbance which needs to be quieted. But this

silence is not achieved by the annihilation of multiplicity. Multiplicity is left

as multiplicity, yet silence prevails, not underneath, not inside, not outside, but

here. The realization of this silence is simultaneously the birth of Christ. They

occur synchronously.

Similarly, the Myōgō enters our active life when there is no longer any

Myōgō but Amida; Amida becomes the Myōgō and the Myōgō becomes Amida.

The last time, I spoke about the relationship between ki, we ordinary beings,

and hō, Amida Buddha, or the Dharma. When the Myōgō is pronounced and we

are conscious of saying Namu to Amida, and when Amida is listening to us say

Namu, there will be no identity, no silence. One is calling out to the other, and

the other is looking down or looking up. There is dualism or disturbance, not

silence.

But when Namu is Amida and Amida is Namu, when ki is hō and hō is ki,

there is silence. That is, the Myōgō is absolutely identifi ed with Amida. The

Myōgō ceases to be the name of somebody who exists outside the one who

pronounces the Myōgō. Then a perfect identity, or absolute identity, prevails,

but this identity is not to be called “oneness.” When we say “one,” we are apt to

interpret that one numerically, that is, as standing against two, three, four, and

so on. But this oneness is absolute oneness, and absolute oneness goes beyond

all measurement. In absolute oneness or identity, the Myōgō is Amida, Amida is

the Myōgō. There is no separation between the two; there is a perfect or absolute

identity of ki and hō.

Shin Buddhism

This is when absolute faith is realized. This is the moment, as indicated by

Shinran, that “Namu-amida-butsu (Myōgō), pronounced once, is enough to save

you.” That “once,” an absolute once, is something utterly mysterious.

Now, jiriki is self-power, and tariki is other-power. The Pure Land school is

known as the Other-power School because it teaches that the other-power is

most important in attaining rebirth in the Pure Land. Rebirth in the Pure Land,

or regeneration, or enlightenment, or salvation—whatever name we may give

to the end of our religious efforts—comes from the other-power, not from the

self-power. This is the contention of the Shin followers.

The other-power is opposed to what is known in theology as synergism. Syn

ergism means that in the work of salvation man has to do his share just as much

as God does his. This is Christian terminology. The Shin school may therefore

be called monergism, in contradistinction to synergism. Syn means together, and

ergism (ergo) means work—“working together.” Monergism means working

alone. Thus in tariki, tariki alone is working, without self-power entering. The

Other-power School therefore is monergism, and not synergism. It is all in the

working of Amida, and we ordinary people living relative existences are power

less to bring about our birth in the Pure Land, or, in another word, to bring about

our enlightenment.

This distinction between synergism and monergism may be described in this

way: The mother cat when she carries her kittens from one place to another takes

hold of the neck of each of the kittens. That is monergism because the kittens

just let the mother carry them. In the case of monkeys, however, baby monkeys

are carried on their mother’s back; the baby monkey must cling to the mother’s

body by means of their limbs or tails. So the mother is not doing the work alone;

the baby monkeys too must do their part. The cat’s way is monergism—the

mother alone does the work; while the monkey’s way is synergism—the two

working together.

In Shin teaching, Amida is the only important power that is at work; we just

let Amida do his work. We don’t add anything of our own to Amida’s working.

This other-power doctrine, or monergism, is based on the idea that we humans

are all relative-minded, and as long as we are so constituted there is nothing

in us or no power which will enable us to cross the stream of birth-and-death.

Amida must come from the other side to carry us on his boat of “all-efficient

vows”—that is, by means of his hongan, his pranidhāna (“vow-prayer”).

There is a deep and impassable chasm between Amida and ourselves, who

are so heavily burdened with karmic hindrance. And we can’t shake off this

hindrance by our own means. Amida must come and help us, extending his arms

from the farther end. This is what is generally taught by the Shin school.

But, from another point of view, however ignorant, impotent, and helpless we

may be, we will never be able to grasp Amida’s arms unless we exhaust all our

own efforts to reach that other end. It is all well and good to say the other-power

does everything on our behalf and we just let it do its work. We must, however,

become conscious of the other-power working in us. Unless we are conscious of

Amida’s doing, we will never be saved. We can never be certain of our birth in

the Pure Land, or the fact that we have attained enlightenment. Consciousness

is necessary. To acquire this consciousness we must strive, exhausting all our ef

forts to cross the stream by ourselves. Amida may be beckoning to us to come to

the other shore where he is standing, but we cannot even see him until we have

done our part to the limit of our power. Self-power may not ultimately carry us

across the stream. But, at the same time, Amida cannot help us by extending his

arms until we have realized that our self-power is worthless, is of no account, in

achieving our salvation. Only when we have made use of our self-power will we

recognize Amida’s help and become conscious of it. Without this consciousness,

there will be no regeneration whatever.

The other-power is all-important, but this all-importantness is known only to

those who have striven by means of self-power to attempt the impossible.

This realization of the worthlessness of self-power may also be Amida’s do

ing. And in fact it is. But until we come to the realization, this recognition—the

fact that Amida has been doing all this for us and in us—would not be ours.

Therefore, striving is a prerequisite for all realizations. Spiritually or metaphysi

cally speaking, everything is ultimately from Amida. But after all we are relative

beings, and so, we cannot be expected to arrive at this viewpoint without having

first struggled on this plane of relativity. The crossing from the relative plane

to the transcendental or absolute plane—or other-power plane—may be impos

sible, logically speaking, but it appears an impossibility only before we have

tried everything on this side. So, the relativity of our existence, the striving or

complete exhausting of ourselves, and self-power—these are all synonyms. In

Japanese, this is known as hakarai. It is a technical term in Shin doctrine.

This may correspond to the Christian idea of pride. Christians are, in a way,

not so philosophical as Buddhists and, except possibly the theologians, do not

use such terms as self-power or other-power. Ordinarily, Christians use the word

“pride,” which exactly corresponds to the Shin idea of jiriki, self-power. This

pride means self-assertion, pride in one’s worthiness, pride in being able to ac

complish something, and so on. To rely on self-power is pride, and this pride

is difficult to uproot, as is self-power. In this relative world, we are constantly

dependent on self-power. On the moral plane, especially, we are forever talk

ing about individual responsibilities, making one’s own choice, and coming to

a decision—all products of self-power. As long as we live in a moral world,

individual responsibility is essential. If we went on without any sense of respon

sibility, society would be in chaos and end in self-destruction. Self-power in this

sense is a necessary part of living in this world of relativity. Self-power, or pride,

is all right as long as things are going on smoothly, when we do not encounter

any hindrance, or anything that frustrates our ambitions, imaginations, or ideals.

But as soon as we encounter something which stands athwart the way we want

to go, then we are forced to reflect upon ourselves.

Such obstructions may be enormous, not only individually but collectively.

Our society is getting more and more complex, the hindrances or obstructions

are becoming more collective in nature and single individuals feel less respon

sible for them. But as long as a society is a community of individuals, each

individual, whether conscious of it or not, will have to be responsible to some

degree for what his society does, for what society imposes upon its members.

When we encounter such hindrances we reflect upon ourselves and fi nd we

are altogether impotent to overcome them. The very moment we encounter

insurmountable difficulties, we reflect, and soon find our self-power altogether

inadequate to cope with the problem. We are seized with feelings of frustration,

breeding in our minds anxiety, uncertainty, fear, and worry—familiar features

of modern life. This is where pride fails to provide an answer. Pride has to curb

itself; it must give way to something higher or stronger. Then pride is humili

ated. As long as we live in our relative world, on this plane of conditionality, we

cannot avoid obstacles and hindrances. We are sure to encounter them.

Earlier Buddhists used to say, “Life is suffering, life is pain.” And we are

compelled to try to escape from it, or to transcend the necessity of being bound

to birth-and-death. They used to use the term “emancipation,” or “liberation,” or

“escape.” Nowadays, instead of such terminology, we say, “to attain freedom,”

or “to transcend,” or “to synthesize,” and so on.

In opposition to the terms “relativity,” “striving,” “self-power,” “hakarai,”

and “pride,” we have “transcending,” “making no efforts.” This relative world

of ours is characterized by all kinds of striving. Unless we strive we can’t get

anything—that is the very condition of relative existence. However, in religious

life, effortlessness prevails—there is no striving. Self-power is replaced by

other-power, pride by humility, hakarai by jinen hōni.

Here are a few more translations or paraphrases of what Shinran, the founder

of the Shin school, says about jinen hōni, that is anata-makase, or “Let thy Will

be done.” It is somewhat scholastic, but it may interest you.

“Ji of jinen means ‘of itself’ or ‘by itself.’” Ji literally means “things as they

are,” or “self,” as it is not due to the designing of man but Amida’s vow that

man is born in the Pure Land. Man is led naturally or spontaneously—this is the

meaning of nen—to the Pure Land. The devotee does not make any conscious

self-designing efforts, for self-power is altogether ineffective to achieve the end

Living in Amida’s Universal Vow: Essays in Shin Buddhism

of being born in the Pure Land. Jinen thus means that because one’s rebirth in

the Pure Land is wholly due to the working of Amida’s vow-power, the devotee

is simply to believe in Amida and let his vow work itself out.

When I say “birth in the Pure Land” I wish this to be understood in a more

modern way. That is, going to the Pure Land is not an event that takes place after

death, but while alive. We are carrying the Pure Land with us all the time. In

fact, the Pure Land surrounds us everywhere. This lecture room itself is the Pure

Land. We become conscious of it, we recognize that Amida has come to help us

only because we have striven and come to the end of our strivings. It is then that

jinen hōni comes along.

“Hōni means ‘It is so because it is so.’” We cannot give any reason for our

being here. Why do we live here? The answer will be, “We live because we

live.” Explanations for our existence will inevitably result in a contradiction.

When we come face to face with such a contradiction we cannot live on even

for a moment. Fortunately, however, contradiction does not get the better of us,

we get the better of contradiction.

In this connection, with the tariki and jiriki, other-power and self-power,

idea, it means this: It is in the nature of Amida’s vow-power that we are born in

the Pure Land. Therefore, the way in which other-power works may be defined

as “meaning with no-meaning.” This is a contradiction or a paradox. When we

talk about “meaning” we wish the word to signify something, but in religious

experience “meaning” is a meaning of no meaning. That is to say, its working is

so natural, so spontaneous, so effortless, so absolutely free, that it works as if it

were not working.

“In order for the devotee to be saved by Amida and be welcomed to Amida’s

Pure Land, he must recite the Myōgō, Namu-amida-butsu, in all sincerity. As far

as the devotee is concerned, he does not know what is good or bad for him. All

is left to Amida. This is what I, Shinran, have learned.”

This is what Shinran says. He does not know good from bad, for all is left to

Amida. This may seem to go directly against our moral consciousness, or what

we call conscience. But from the religious point of view, what we think is good

is not necessarily good all the time, or absolutely good. For good may turn into

bad at any time and vice versa. So we cannot be the absolute judge of moral

good or moral evil. When by Amida’s help we go beyond all this, and everything

is left to Amida’s working, when we realize or become conscious of Amida’s

working in everything we do, whether it be good or bad, then all is good. As

long as we live on the relative plane, this will remain a paradox, inexplicable

and incomprehensible.

Shin Buddhism

“Amida’s vow,” Shinran continues, “is meant to make us all attain supreme

Buddhahood.” As I said before, when supreme enlightenment is attained, we

realize the actual existence of the Pure Land, the fact that we are right in the

midst of the Pure Land. Supreme Buddhahood, which is the same as supreme

enlightenment, is realized when we find we are in the Pure Land itself.

Shinran goes on: “Buddha is formless, and because of his formlessness he is

known as ‘all by itself.’” All physical things have forms, and ideas have some

thing to designate, but when Buddhists say “formlessness,” they mean neither

physical form nor intellectualization. We are in the world of “formlessness”

when we go beyond the materiality of things and our habits of intellectualizing.

The Buddhist term “formlessness” is also known as jinen, “all by itself,” “to

exist by itself.”

“If Amida had a form he would not be called Supreme Tathāgata, Nyorai. He

is called Amida in order to let us know his formlessness. This is what Shinran

has learned. Once you have understood this you need not concern yourself with

jinen any longer.” This is important. When we realize that we are really in the

world of “formlessness,” we need not talk about jinen, “being by itself,” any

more.

Shinran goes on: “When you turn your attention to it, the meaningless mean

ing assumes a meaning, defeating its own purpose.” When we talk about “being

by itself,” we no longer are “being by itself”; there is no more “meaningless

meaning.” Meaning has something to mean; it points to something else. When

we are that meaning itself, we need not talk about meaning any more. When

we are jinen itself, there is no more need to discuss it because we are jinen.

As soon as we begin to think, all kinds of difficulties arise, but when we don’t

think, everything is all right. By “not thinking,” I don’t mean that we must be

animal-like; we must remain human and yet be like “the lilies of the fi eld,” or

“the fowls of the air.” Shinran says, “All this comes from butchi (Buddhajñā;

Buddha-intellect, or Buddha-wisdom).” Butchi is something that goes beyond

our relative way of thinking; it is the “other-power.” The term other-power is a

more dynamic conception; while butchi is more dialectic or metaphysical.

From his commentary on Jinen Hōni (“Being by Itself”), we can see what

understanding Shinran had of the working of Amida’s vow-power, or of the

other-power. “Meaningless meaning” may be thought of as something devoid

of sense—literally, meaningless, without any definite content whereby we can

concretely grasp its significance. But the idea is this: there was no teleology or

eschatological conception on the part of Amida when he made those forty-eight

vows. All the ideas expressed in them are the spontaneous outflow of his great

infinite compassion, his great compassionate heart, embracing everything and

extending to the farthest and endless ends of the world. And this infi nite com

passion is Amida himself. Amida has no ulterior motive. He simply feels sorry

for us suffering beings, and wishes to save us from going through an endless

cycle of birth-and-death. Amida’s vows are the spontaneous expression of his

Living in Amida’s Universal Vow: Essays in Shin Buddhism

love or compassion. This “going beyond teleology,” or “purposelessness” may

sound strange at first, for everything we do in this world usually has a purpose.

But religious life consists in attaining this “purposelessness,” “going beyond

teleology,” “meaningless meaning,” and so on. This is what is called anata

makase, or “Let thy Will be done,” “going beyond self-power and letting Amida

do his work through us or in us.” Thus there are no prayers in Buddhism in the

strict sense of the term. For when you pray to gain something you will never get

anything; when you pray for nothing you gain everything.

During the Tokugawa era, there was a man in Japan called Issa who was

noted for his haiku. Issa expressed his idea of “Let thy Will be done,” but in his

case it has no religious implication. In fact, he was being pressed by worldly

affairs, and it was out of his desperate situation that he uttered this haiku at the

end of the year. I still remember when I was very young we paid everything we

owed to the tradespeople at the end of the year. In my day it was twice a year,

once in July and once at the year end. If we could not pay by mid-July, we left it

to the end of the year, and if we could not pay then, we went broke. Issa was in

a similar predicament. I will give his verse first in Japanese. Those who under

stand Japanese might appreciate it:

Tomokaku mo

Anata-makase no

Toshi no kure

Issa was obviously in great distress: “I, being at the end of the year, having

no money whatever to pay my accounts, have no choice but to let Amida do his

Will.” If indeed Amida could look after Issa’s problem, all would be well, for

Issa was really desperately poor. In fact, worldly poverty and spiritual “poverty”

often have a great deal to do with each other, going hand in hand.

In reading Eckhart, I found a story you might like to hear. It is entitled

“Meister Eckhart’s daughter”:

A daughter came to the preaching cloister and asked for Meister Eckhart. The

doorman asked, “Whom shall I announce?”

“I don’t know,” she said.

“Why don’t you know?”

“Because I am neither a girl, nor a woman, nor a husband, nor a wife, nor a widow,

nor a virgin, nor a master, nor a maid, nor a servant.”

The doorman went to Meister Eckhart and said:

“Come out here and see the strangest creature you ever heard of. Let me go with

you, and you stick your head out and ask, ‘Who wants me?’”

Shin Buddhism

Meister Eckhart did so, and she gave him the same reply she had made to the

doorman. Then Meister Eckhart said:

“My dear child, what you say is right and sensible, but explain to me what you

mean.”

She said:

“If I were a girl, I should be still in my first innocence; if I were a woman, I should

always be giving birth in my soul to the eternal word; if I were a husband, I should put

up a stiff resistance to all evil; if I were a wife, I should keep faith with my dear one,

whom I married; if I were a widow, I should be always longing for the one I love; if

I were a virgin, I should be reverently devout; if I were a servant-maid, in humility I

should count myself lower than God or any creature; if I were a man-servant, I should

be hard at work, always serving my lord with my whole heart. But since of all these I

am neither one, I am just a something among somethings, and so I go.”

Then Meister Eckhart went in and said to his pupils:

“It seems to me that I have just listened to the purest person I have ever known.”

(Blakney translation, pp. 252-3).

This is quite an interesting story. But I have something to say here: This

strange daughter said, “Of all these, I am neither one.” That is, she is not any

of all those enumerated above. She mixes the worldly sense with the spiritual

sense; that is, for example, “if I were a husband, I should put up a stiff resistance

to all evil.” This may be taken in a worldly or in a spiritual sense, I believe. If

one were engaged in spiritual life, or otherwise, there will be some end to per

form. If you designate this or that, if you have some work to accomplish, some

role to perform, you will have something. But she says, “Since of all these I am

neither one, I am just a something among somethings … ”

I wouldn’t say this. I would say, “I am just a nothing among somethings, and

so I go.” “So I go” is jinen hōni. It is sonomama. It is “Let thy Will be done.”