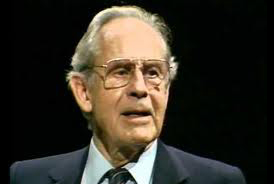

by Eliott Wright: “I’m not afraid to admire Paul Tillich. He has been my spiritual father. I learned from him and loved him. Strangely, that seems to enrage many people.”

Rollo May, the psychoanalyst and author who is well known in religious circles, sat in his Manhattan office discussing with me critics’ reactions to his Paulus, a small appreciative volume subtitled “Reminiscences of a Friendship,” which was published (by Harper & Row) in October 1973. In the same month and year Hannah Tillich, widow of the theologian who died in 1965 at the age of 79. issued an autobiography, From Time to Time (Stein & Day), which presents a more ambivalent, perhaps bizarre, picture of her husband.

The interview he granted me was the first in which May talked about the background of Paulus, its contents in relation to Mrs. Tillich’s account, and his concern over what the reception of both books says about contemporary culture.

“My book has elicited so much anger,” he said. “It seems to me it’s anger that one should present a man as a hero. Some people say that I thought too much of Paulus, that I don’t make him flesh and blood. One review complained that I compared Paulus’s death with Socrates’. Well, I must say that is a bit idealized. Yet it’s a very real thing which I felt. Hannah shows him at his death with his bowels erupting, which strikes me as typical of what we do with our great men: show them defecating, no different from you and me.”

I

Paulus and From Time to Time were inevitably reviewed together. And practically all the reviews — from the scintillating paragraphs inTime magazine’s October 8, 1973, issue to the impassioned piece in Psychology Today for April 1974 — stressed the widow’s description of Tillich as “lover of myriad women” (to use a southern paper’s phrase). By comparison, many reviewers treated May’s interpretation of Tillich’s sensuality as demure.

“It saddens me to say this, but I must speak out: I don’t think Hannah’s book presents an accurate picture of Paulus,” May declared. “It presents him as a kind of adolescent voyeur and implies there were actual sexual relationships between him and a long series of women. That’s not true.

“Now Paulus did greatly admire women and could be quite sensuous. He loved to hold a woman’s hand, talk intimately with her. . . well, one could call it a spiritual seduction that had little to do with sexual intercourse.

“Hannah also distorts Paulus’s life by saying almost nothing about his intellectual greatness, nothing about his being an impressive writer, nothing about his ecstatic reason. The things that make Tillich significant are left out. What this does, unless a reader already knows him, is to give a warped portrait; another dirty old man.”

The Psychology Today review, written by John Wren-Lewis, says that Paulus “appears to be a hasty production, so much so as to suggest the nasty suspicion that it might have been rushed out in the hope of counterbalancing the possible scandal of Hannah’s revelations.” A review appearing in Newsday last December said the same thing, but in the form of a question.

“Nonsense,” May retorted. The truth is that he agreed to write the book only at the Tillich family’s request. He explained:

“Hannah actively urged me over several years to write what she called the ‘authorized biography.’ I had known her and Paulus since a month after they arrived in the U.S. in 1933, when I was a student at Union Seminary. As I began making notes, I saw ‘that I had neither the time nor the facts on the German period to write an ‘authorized biography.’ I decided to concentrate on where our two lives overlapped.”

Records made available by Harper & Row show that May signed a contract for a Tillich book in 1967, and that by early 1969 the concept of a personal memoir had emerged. But May had to fulfill commitments on Love and Will and Power and Innocence to another publisher (Norton) before he could give full attention to Paulus. He began writing that in spring 1972. For six months after publication of Paulus,May declined to grant any interviews regarding it. But charges that his volume was “rushed” out and that, when compared with From Time to Time, it contains errors of fact, were one reason why he changed his mind. May cited two other reasons.

First, the Tillich Society in Germany issued a “warning” to German publishers not to issue any translation of Mrs. Tillich’s book, which the society said contains “weighty distortions” and “misrepresentations” of Tillich. Second, the British publisher of Paulus is asking May to write a special preface frankly stating the relationship between the two books.

‘‘I decided it is important to set the record straight in this country. May said.

II

What are your major concerns in light of the widespread attention ‘Paulus’ and ‘From Time to Time’ have drawn?

My major concern is that Paul Tillich has been presented in such a way that not only is he not given fair treatment in terms of the so-called “sexiness,” but his ideas are neglected. I have chapters on Paulus’s ‘‘agony of doubt’’ and his great ability in logic. These are ignored.

You feel that Tillich, the theologian and philosopher, is being ignored?

Precisely. I think the most important issue in this whole thing is the anti hero mood of our society. We have a great need to scandalize, to gloat over the foibles of important figures. Nobody can rise above the mass. It’s a sickness typical of the present stage in our decadent era.

Moral decadence? Political decadence?

Spiritual and psychological decadence. Tillich used to say we are living in the last century of the modern period, which began at the Renaissance, and like the Middle Ages and the Greek era we are caught in the midst of radical change and its accompanying spiritual malaise. One symptom of the morass we are in is that we have no more heroes. Once we lose our heroes we also lose our morale. We have no one to guide us, no one to teach us.

You mean the teacher is a heroic model?

Partly. But essentially for a teacher to have any influence or power he must have listeners. Somebody must want to listen — and that’s quite rare today. We mock our teachers: they don’t rate like men who enter the business world and make money. This is part and parcel of the loss of our sense of reverence lot persons. Watergate is just a minor symbol of the disintegration of our esprit de corps. Decadence is what is going on, and in odd but different ways Hannah’s book and my book fit right into it.

In what sense?

Here is part of the decadence movement, the scandalizing and cutting down of a giant to ordinary size. The anger my Paulus has aroused seems bent on leveling out a great teacher. An egalitarian society finds reassurance when a man of Paulus’s stature is shown with all the petty adulteries of everybody else. We have substituted conformism for democracy.

Would you expand on anger as a response to your book?

Yes. I had a difficult time understanding it because it isn’t anger over what I say or over disagreements on minor facts. It’s an irrational anger, expressing itself in such irrelevant things as holding me responsible for a printer’s error about Paulus’s birthday in the first copies off the press.

Questions have also come up as to whether the comment “today is dying day” should be attributed to Tillich on the morning of his last day or at some other time in his final illness.

That also seems to me irrelevant, though I might say that I took my information on the death from an account Hannah wrote and gave me back in 1966. What’s important is the way such details are used to support rage — a rage, I believe, that anyone should have a hero.

III

Were you aware that Mrs. Tillich was planning a book when you were preparing yours?

At a point. Hannah has always written. Her travel diaries are quite good. She has also written poems and fables, and things about her sexual relationships with various people. A lot of that is in From Time to Time. I was not aware that she was thinking of publishing that material until 1972. During the early part of the year she kept saying I must read her manuscript, and I kept avoiding it because I knew the problem we would get into if I did. Remember, I have known Hannah for 40 years. That summer — 1972 — she brought the manuscript along when she visited us in New Hampshire, and I realized I would have to read it.

What was your reaction?

Like most of her and Paulus’s friends, I tried to persuade her not to publish it. I wrote her a long letter saying I thought it would give a distorted picture of Paulus and their relationship and would be most humiliating to her. It would appeal to that aspect of our culture that likes to see people flagellate themselves in public. I told her that if the manuscript was published it would be because she had happened to be Paul Tillich’s wife. All the publishers who read it in 1972 turned it down. Paulus was officially announced in January 1973. Then in February Hannah secured a publisher. I stopped work on my almost complete biography. It seemed obvious that both books would be coming out at the same time, and I did not want that to occur.

Why did you stop work?

I was sick about the whole thing. I felt . . . sick is the best word. As I look back. I don’t know whether it was a good idea to publish Paulusor not. But at the time my friends convinced me it was important to finish my biography and provide two versions of Paul Tillich.

And you think your version is the more factual on the sensual side of Tillich?

I do. An admiring student may not be the most objective judge of a teacher, but a wife is considerably less reliable. “No man is a hero to his valet.”

Why would Mrs. Tillich want to misrepresent her husband?

Hannah is an emotional German woman who was made jealous many, many times by Paulus. She talks about her jealousy in her book. She felt his interest in other women was a threat to her. I have no arguments against taking revenge, if one wants it. Yet I feel it is unfortunate that Hannah waited until after Paulus’s death to take hers.

Did Mrs. Tillich cooperate with you, share documents and her reminiscences?

Certainly. She implored me to write the book in the beginning.

Did she read your biography before publication?

Oh yes, when it was put into proof by Harper. And she liked it. She described it as an affectionate and loving portrait of Paulus.

Some of the reviews treat her book as an exercise in women’s liberation.

Well, it is true that Hannah was married to a man who, regardless of his modern ideas on theology and art, was a product of the old Germany. So was she. Paulus expected her to get up and get his breakfast. She persuaded him to spend a little time with their two children, but like most German fathers he found our American way of dealing with youngsters — the child ordering the adult around — contrary to his training. Hannah had to take quite a bit of gaff, though no more than any woman out of Weimar, Germany, would have taken. She always drove the car, made the arrangements for travel. At times I felt sorry for her. Yet she seemed to enjoy it; she liked to meet the important people she met because she was Mrs. Paul Tillich.

It’s all to the good when a previously downtrodden woman speaks out, but I don’t think the thesis “a woman declares her freedom at last” can carry all the weight put on it in Hannah’s case. This woman speaking out is Paul Tillich’s widow. Remove that fact and I doubt thatFrom Time to Time could sustain itself as a women’s liberation piece.

IV

Could we return to the issue of sensuality, which seems to be the most controversial subject in the two books?

Perhaps we should. Paulus was a very sensual man. He came from a Lutheran background, not the Puritan background we have in the U.S. and England. Like Luther, he believed in the robustness of the body. He was a great mountain climber, could walk forever, never wore a hat. His physical robustness was appealing and endearing. He loved food and drink. He liked nightclubs. Everybody knows those things about him. Paulus had a great joie de vivre, greater than Hannah’s. He could throw himself into a situation with a zest that was quite unusual. Hannah tended to be shy. Paulus loved parties and this reflected his joy in being with people. His relation to women is an epitome of that joy. Paulus thought every woman beautiful. He was loving and tender with them. But it was not an act; his emotions were real and women responded. I know many women who feel that his friendship was a great moment in their lives.

And sexual intercourse was not involved in these relationships?

To my knowledge, only a few times, and I knew Paulus intimately as well as a number of the women. And those few times, only when he had known the women over a period of time.

Was he sexually pursued by women?

Undoubtedly some women would have liked him to go further than he did. Not many, I think. By and large, they knew what Paulus was getting across. The Psychology Today review says for Paulus to relate to women as I say he did was ‘nastier” than to have actual sexual intercourse. That moralistic statement misses the point. The women knew and Paulus knew that they were not going to end up in bed. Paulus’s motivation was the glory of loving and appreciating women, not the glory of intercourse.

Hannah leaves the impression Paulus was a prurient person trying to get as many women as possible into bed. This is a distortion of fact and, more seriously, a distortion of his character. Yet people want to hear and see the prurient. I have the feeling that Sartre’s view of society in The Flies fits us today. The people in the play hold a great celebration of guilt. That fits Watergate and in some ways our whole society.

Was that not also the Weimar society out of which Tillich came?

Exactly. But, you see, Paulus had a “system” — he called it Christian socialism — that might have ameliorated the conflicts in the Weimar Republic had the people been in the mood to listen.

Do you think Tillich’s reputation as theologian has been permanently damaged in the past six months?

We can only wait and see. Some people tell me they are more interested in the man Paulus after reading about Tillichian sex-capades. But I don’t see much real interest in his significant writings. The theologian seems to get lost in all the publicity. I am afraid the depth and breadth of Paulus’s ideas and his sorely needed contribution to our culture will be forgotten in the mêlee.