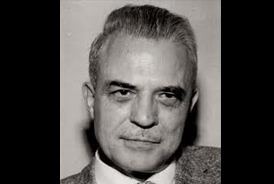

Excerpted from Experimental Hypnosis, by Leslie LeCron, from a chapter titled: “Deep Hypnosis Techniques”

by Milton Erickson: For want of a better term, one of these special procedures may be termed the “confusion technique.” It has been employed extensively for the induction of specific phenomena as well as deep trances. Usually, it is best employed with highly intelligent subjects interested in the hypnotic process, or with those consciously unwilling to go into a trance despite an unconscious willingness.

In essence, it is no more than a presentation of a whole series of individually differing, contradictory suggestions, apparently all at variance with each other, differently directed, and requiring a constant shift in orientation by the subject. For example, in producing hand levitation, emphatic suggestions directed to the levitation of the right hand are offered together with suggestions of the immobility of the left hand. Shortly, the subject becomes aware that the hypnotist is apparently misspeaking, since levitation of the left hand and immobility of the right are then suggested.

As the subject accommodates himself to the seeming confusion of the hypnotist, thereby unwittingly cooperating in a significant fashion, suggestions of immobility of both hands are given, together with others of the simultaneous lifting of one and pressing down of the other. These are followed by a return to the initial suggestions.

As the subject tries, conditioned by his early cooperative response to the hypnotist’s apparent misspeaking, to accommodate himself to the welter of confused, contradictory responses apparently sought, he finds himself at such a loss that he welcomes anv positive suggestion that will permit a retreat from so unsatisfying and confusing a situation. The rapidity, insistence, and confidence with which the suggestions are given serve to prevent the subject from making any effort to bring about a semblance of order. At best, he can only try to accommodate himself and, thus, yield to the over-all significance of the total series of suggestions.

Or, while successfully inducing levitation, one may systematically build up a state of confusion as to which hand is moving, which more rapidly or more laterally, which will become arrested in movement, and which will continue and in what direction, until a retreat from the confusion by a complete acceptance of the suggestions of the moment becomes a greatly desired goal.

In inducing an extensive atnnesia with a regression of the subject to earlier patterns of behavior, the “confusion technique” has been found extremely valuable and effective. It is based upon the utilization of everyday experiences familiar to everyone. To regress a Subject to an earlier time in his life, a beginning is made with casual conversational suggestions about how easy it is sometimes to become confused as to the day of the week, to misremember an appointment :as of tomorrow instead of yesterday, and to give the date as the old year instead of the new. As the subject correlates these suggestions with his actual past experiences, the remark is made that, although today is Tuesday, one might think of it as Thursday, but, since today is Wednesday and, since it is not important for the present situation whether it is Wednesday or Monday, one can call to mind vividly an experience of one week ago on Monday, that constituted a repetition of an experience of the previous Wednesday. This, in turn, is reminiscent of an event which occurred on the subject’s birthday in 1948, at which time he could only speculate upon but not know about what would happen on the 1949 birthday and, even less so, about the events of the 1950 birthday, since they had not yet occurred. Further, since they had not occurred, there could be no memory of them in his thinking in 1948.

As the subject receives these suggestions, he can recognize that they carry a weight of meaningfulness. However, in order to grasp it, his tendency is to try to think in terms of his birthday of 1948, but to do so he has to disregard 1949 and 1950. Barely has he begun to orient his thinking when he is presented with another series of suggestions to the effect that one may remember some things and forget others, that often one forgets things he is certain he will remember but which he does not, that certain childhood memories stand out even more vividly than memories of 1947, ’46, ’45, that actually every day he is forgetting something of this year as well as last year or of 1945 or ’44, and even more so of ’42, ’41, and ’40. As for 1935, only certain things are remembered identifiably as of that year and yet, as time goes on, still more will be forgotten.

These suggestions are also recognized as carrying a weight of acceptable meaningfulness, and every effort the subject makes to understand it leads to acceptance of them. In addition, suggestions of amnesia have been offered, emphasis has been placed upon the remembering of childhood memories, and the processes of reorientation to an earlier age level are initiated.

These suggestions are given not in the form of commands or instructions but as thought-provoking comments, at first. Then, as the subject begins to respond, a slow, progressive shift is made to direct suggestions to recall more and more vividly the experiences of 1935 or 1930. As this is done, suggestions to forget the experiences subsequent to the selected age are given directly, but slowly, unnoticeably, and these suggestions are soon reworded to “forget many things, as naturally as one does, many things, events of the past, speculations about the future, but of course, forgotten things are of no importance-only those things belonging to the present thoughts, feelings, events, only these are vivid and meaningful.” Thus, a beginning order of ideas is suggested, needed by the subect but requiring a certain type of response.

Next, suggestions are offered emphatically, with increasing intensity, that certain events of 1930 will be remembered so vividly that the subject finds himself in the middle of the development of a life experience, one not yet completed. For example, one subject, reoriented to his sixth birthday, responded by experiencing himself sitting at the table anxiously waiting to see if his mother would give him one or two frankfurters. The Ph.D. previously mentioned was reoriented to an earlier childhood level and responded by experincing herself sitting in the schoolroom awaiting a lesson assignment.

It is at this point that an incredible error is made by many serious workers in hypnosis. This lies in the unthinking assumption that the subject, reoriented to a period previous to the meeting with the hypntist, can engage in conversation with the hypnotist, literally a nonexistent person. Yet, critical appreciation of this permits the hypnotist to accept seriously and not as a mere pretense a necessary transformation of his identity. The Ph.D., reliving her school experience, would not meet the author until more than 15 years later.

So she spontaneously transformed his identity into that of her teacher, and her description as she perceived him in that situation, hter checked, was found to be a valid description of the real teacher. F or Dr. Erickson to talk to her in the schoolroom would be a ridiculous anachronism which would falsify the entire reorientation. With him seen as Miss Brown and responded to in the manner appropri- ate to the time, the schoolroom, and to Miss Brown, the situation beecame valid, a revivification of the past.

Perhaps the most absurd example of uncriticalness in this regard is the example of the psychiatrist who reported at length upon his experimental regression of a subject to the intrauterine stage, at which he secured a subjective account of intrauterine experiences. He disregarded the fact that the infant in utero neither speaks nor understands the spoken word. He did not realize that his findings were the outcome of a subject’s compliant effort to please an uncritical, unthinking worker.

This need for the hypnotist to fit into the regression situation is itnperative for valid results, and it can easily be accomplished. A patient under therapy was regressed to the age level of 4 years. Itmformation obtained independently about the patient revealed that, at that time in her life, she had been entertained by a neighbor’s gold hunting-case watch, a fact she had long forgotten. In regressing her, as she approached the 4-year level, the author’s gold hunting-case watch was gently introduced visually and without suggestion. His recognition as that neighbor was readily and spontaneously achieved. This transformation of the hypnotist into another person is not peculiar only in regression work.

Many times, in inducing a deep trance in a newly met subject, the author has encountered difficulty until he recognized that, as Dr. Erickson, he was only a meaningless stranger and that the full development of a deep trance was con- tingent upon accepting a transformation of his identity into that of another person. Thus, a subject wishing for hypnotic anesthesia for childbirth consistently identified the author as a former psychology professor, and it was not until shortly before delivery that he was accorded his true identity. Failure to accept seriously the situation would have militated greatly against the development of a deep trance and the training for anesthesia.

Regardless of a hypnotist’s experience and ability, a paramount consideration in inducing deep trances and securing valid responses is a recognition of the subject as a personality, the meeting of his needs, and an awareness and a recognition of his patterns of unconscious functioning. The hypnotist, not the subject, should be made to fit himself into the hypnotic situation.

-END-