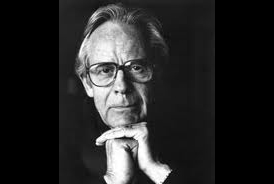

Hello and welcome. I’m Jeffrey Mishlove. Our topic today is existential psychology, and with me is Dr. Rollo May. Dr. May is one of the founding sponsors of the Association for Humanistic Psychology,  and a genuine pioneer in the field of existential psychology and clinical psychology. He was recently awarded the Distinguished Career in Psychology Award by the American Psychological Association. He is the author of numerous classic books, including

and a genuine pioneer in the field of existential psychology and clinical psychology. He was recently awarded the Distinguished Career in Psychology Award by the American Psychological Association. He is the author of numerous classic books, including

The Courage to Create, Love and Will, The Meaning of Anxiety, Freedom and Destiny, and Psychology and the Human Dilemma. Welcome, Dr. May.

ROLLO MAY, Ph.D.: Thank you.

MISHLOVE: It’s a pleasure to have you here. You’re really most known these days, I think, as a pioneer in establishing existential psychology as an independent discipline in the clinical area. That’s a discipline which, unlike most forms of clinical psychology that rely on a medical model or a behavioral model, relies more on a philosophical model. You draw heavily on the works of philosophers such as Sartre, Heidegger, and Kierkegaard, who deal with basic notions such as anxiety in a different way than most medical clinical models do.

MAY: Yes. Well, in the year I think ’56 or ’57, the publishers called me up and asked if I would edit a book on European existential psychotherapy. I was delighted to hear there was such a book. I hadn’t known a thing about the existential movement, but I knew that in this country I believed in it very firmly, because they are the ones who emphasize anxiety, they emphasize the individual, courage, they emphasize guilt feeling, that it has to be taken into consideration at least, and they see human beings as struggling, sometimes successful, sometimes not successful. This was exactly the model that we needed for psychotherapy. The medical model had turned out to be a dead end, and I welcomed the chance to edit this book of existential chapters from Europe. It met my own needs and my own heart.

MISHLOVE: Would I be correct in assuming that when you speak of anxiety you don’t think of it as a symptom to be removed, but rather as a gateway for exploration into the meaning of life?

MAY: Yes. Well, you’ve got that exactly right. I think anxiety is associated with creativity. When you’re in a situation of anxiety, you can of course run away from it, and that’s certainly not constructive; or you can take a few pills to get you over it, or cocaine, or whatever else you may take.

MISHLOVE: You could meditate.

MAY: Well, you could meditate. But I think none of those things, including meditation, which I happen to believe in — none of those paths lead you to creative activity. What anxiety means is it’s as though the world is knocking at your door, and you need to create, you need to make something, you need to do something. I think anxiety, for people who have found their own heart and their own souls, for them it is a stimulus toward creativity, toward courage. It’s what makes us human beings.

MISHLOVE: I suppose much of our anxiety comes from the basic human dilemma of being mortal, of ultimately having to confront our own demise.

MAY: We are conscious of our own selves, our own tasks, and also we know we’re going to die. Man is the only creature — men, women, and children sometimes even, are the only creatures who can be aware of their death, and out of that comes normal anxiety. When I let myself feel that, then I apply myself to new ideas, I write books, I communicate with my fellows. In other words, the creative interchange of human personality rests upon the fact that we know we’re going to die. Of that the animals and the grass and so on know nothing. But our knowledge of our death is what gives us a normal anxiety that says to us, “Make the most of these years you are alive.” And that’s what I’ve tried to do.

MISHLOVE: Another source of anxiety that you’ve described in your writing is our very freedom — our ability to make choices, to have to confront the consequences of those choices.

MAY: Yes, that’s right. Freedom is also the mother of anxiety. If you had no freedom, you’d have no anxiety. That’s why the slaves in the films are people without any expression on their faces; they have no freedom. But those of us who do have, are alert, alive. We’re aware that what we do matters, and that we only have about seventy or eighty or ninety years in which to do it, so why not do it and get joy out of it, rather than running away from it? I think that’s a little capsule of the meaning of anxiety.

MISHLOVE: But isn’t there a little bit of a conflict between feeling anxiety and allowing oneself to be open, vulnerable, to that feeling of anxiety, and then also seeking joy?

MAY: Oh no. There’s a conflict between that and what’s generally called happiness, or the flat, I would speak of the meaningless forms, of feeling good. I’m not against anybody feeling good or having happy hours, but joy is something different from that. Joy is the zest that you get out of using your talents, your understanding, the totality of your being, for great aims. Musicians, men who wrote music — Mozart and Beethoven and the rest of them — they always showed considerable anxiety, because they were in the process of loving beauty, of feeling joy when they heard a beautiful combination of notes. That’s the kind of feeling that goes with creativity. That’s why I say the courage to create. Creation does not come out of simply what you’re born with. That must be united with your courage, both of which cause anxiety but also great joy.

MISHLOVE: It seems that much of our modern culture, though, is an attempt to cope with this fundamental anxiety by diversions and what you’ve called banal pleasures.

MAY: Yes, well, you’ve just put your finger on the most significant aspect of modern society. We try to avoid anxiety by getting rich, by making a hundred thousand dollars when we’re twenty-one years of age, by becoming millionaires. Now none of those things lead to the joy, the creativity that I’m talking about. One can own the world and still be without the inner sense of pleasure, of joy, of courage, of creation. I think our society is in the midst of a vast change. The society that began at the Renaissance now is ending, and we are seeing the results of this ending of a social period in the fact that psychotherapy has grown with such great zest. Almost every other person in California is a psychotherapist.

MISHLOVE: It seems that way.

MAY: Yes, it does. And this always happens when an age is dying. You see, the Greeks began their great age in the seventh, sixth centuries B.C., and then they talked of beauty and goodness and truth, all these great things that the philosophers talked about. But by the second century B.C., first century B.C., that had all been forgotten. The philosophers now talked about security, and they tried to help people get along with as little pain as possible, and they made mottoes for human beings. Beauty and truth and goodness had been lost. Our Renaissance began the modern age, and at the beginning of an age there are no psychotherapists. This is taken care of by religion and by art and by beauty, by music. But at the end of an age — every age down through history has been the same — every other person becomes a therapist, because there are no ways of ministering to people in need, and they form long lines to the psychotherapist’s office. I think it’s a sign of the decadence of the age, rather than a sign of our great intelligence.

MISHLOVE: I know in your book Love and Will you refer to the great poem by T.S. Eliot, The Waste Land, and the way so many people when it was first written at the early part of this century seemed to relate to it, not understanding its prophetic nature — it seemed to characterize the emptiness of modern society.

MAY: Yes, the king in The Waste Land, remember, was impotent. The wheat and the grass did not grow. Therefore it was a waste land. And he goes on in marvelous detail. Now, just about that time, in the 1920s, in the Jazz Age, there was written another book that is prophetic. That is The Great Gatsby. The movie was terrible, but forget the movie, and take the book.

MISHLOVE: F. Scott Fitzgerald.

MAY: F. Scott Fitzgerald. It’s a small book. It’s a marvelous picture of how our age is disintegrating. He ultimately dies, and dies a completely lonely man. There is nobody at the funeral, and it’s a tragedy. But Fitzgerald saw that this was happening not in the Jazz Age — then everybody was earning lots of money and trying out new styles, just like nowadays. But he knew what was going to happen, and therefore The Great Gatsby. We are now in the age when those things, The Waste Land and The Great Gatsby, are coming to fruition. That’s why I believe that if our world survives the nuclear threat — and I believe it will

— if it survives that we will move into a new age, when the emphasis will not be on making piles and piles of money and being scared to death the stock market is going to drop tomorrow, but rather the emphasis will be on truth, on joy, on understanding, on beauty — these things that to my mind make life really worth living.

MISHLOVE: You’ve also characterized our present age as one in which modern man seems to be robbed of his own free will, and observed that through Freudian psychology and other scientific movements we see the human being as influenced by deterministic forces, threats of great social movements, nuclear war, and so on — that there’s nothing that we can do, and there’s a feeling of helplessness, alienation. And yet you suggest that through philosophical and existential exploration we can enter into, in effect, another state of consciousness, where we reconnect with our will at a deeper level.

MAY: Yes, this is why I wrote Love and Will, because you cannot love unless you also can will. I think, and thought when I wrote that book, that a new way of love would come about. People would learn to be intimate again. They would write letters. There would be a feeling of friendship among people. Now, this is the new age that is coming, and I don’t think it’s a matter chiefly of philosophy. See, nowadays there are no philosophers; the last philosopher in this country was Paul Tillich. People now have given up, and they now call philosophy the kibitzing on science — a way of simply looking over the scientist’s shoulder, and seeing how they can help science put things together. That’s not philosophy. Philosophy is a deep search for a truth by which I can fulfill myself, by which I can create. Philosophy is the basis of freedom. It’s the basis of goodness, too, which seems to not trouble many modern people, but I think it’s a great mistake, because of all of our lack of ethics, our lack of morality. We need goodness, and we need beauty. All of those are philosophical terms, but beyond that — see, I’m really a psychotherapist, after saying all these nasty things about psychotherapy. It is the way we have in our end of the twentieth century of helping many people to find themselves and a way of life that will be satisfying, and will give them the joy that human beings certainly have a right to have. I’m not ashamed at all that I’m a psychotherapist. I became a therapist because I saw that’s where people unburden themselves, and that’s where people will show what they have in their hearts. They don’t show that in philosophy, and in most religions these days they also don’t show it. This is why so many people in California join the cults. Now, I happen to believe in meditation, and I do it myself, and we’ve learned a lot of things from India and Japan. But we cannot be Indians or Japanese, and we must find a form of religious observation, religious experience, that will fit us as pioneers of the twenty-first century.

MISHLOVE: A couple of moments ago you referred to the term a new age, and of course the new age is kind of a popular term these days for a wide scope of activities. I would gather from my familiarity with your work that you’re critical of a good deal of this, as glossing over basic human pain and attempting to make nice. I suppose these are some of the same criticisms, perhaps, that Freud had of religion.

MAY: Exactly. It’s very good to talk with you because you’ve read what I’ve written, and you know exactly which way to turn. No, I don’t like the new age movement. I think it’s oversimplified, makes everybody feel temporarily happy, but they avoid the real problems. The new age can come only as we face anxiety, as we face guilt feeling for our misapprehension of what’s the purpose of life, as we face death as a new adventure. Now, none of these things does the new age talk about. It talks about only being gleeful, and everybody singing songs.

MISHLOVE: But you know, I’ve sensed another paradox here. I noticed in your book Freedom and Destiny that you have a section on mysticism, and you refer to the great Western mystics Jacob Boehme and Meister Eckhart and their search for the divine fire within themselves, and you seem to see that almost — I don’t know quite what to say — almost as a model of deep existential probing.

MAY: Surely, oh yes. I’m very much a believer and follower of these mystics in our tradition. I’m not a believer and follower of Rajneesh, or the other —

MISHLOVE: Maharishi.

MAY: Or Maharishi. Muktananda I found the most companionable of these leaders, but most of them that come from India build up cults and get into all kinds of trouble, and they’re sued for millions of dollars, and the cult then collapses. Or like Jim Jones, who took nine hundred people to an island, and there they were going to set up a perfect community, and they all committed suicide, nine hundred and nineteen of them.

MISHLOVE: But my sense is that your criticism goes much deeper than just the scandals themselves. My sense is that what you’re saying is that in this retreat to a mystical lotus land, or perhaps even beliefs such as spiritualism and reincarnation, that people are losing touch with the basic issues of their very existence.

MAY: Oh, absolutely. You said it beautifully. I’m very critical of these movements that soft-pedal our problems, and that indicate that we should forget them. I think the mystics that you and I were talking about — Jacob Boehme was burned at the stake, and the other Christian mystics, or mystics of Mohammedanism and so on — back in our tradition, are very important, and though the Church at the time opposed them, they nevertheless left great books full of knowledge that we can read, we can understand, we can learn from.

MISHLOVE: I know that some of the existentialist philosophers, such as Camus and Sartre and perhaps even Genet, made quite a bit out of the idea of rebelling against the conventional mores of society. I sense that what you’re saying is that genuine mysticism has to also involve this kind of cutting-edge rebellion against the herd instincts.

MAY: Yes, it does. It’s a rebellion against the herd instinct. Sartre was very important in this movement of the rebel. Camus wrote the book The Rebel. And Paul Tillich, who was my dear and very close friend for some thirty years, he and the others of the existentialists understood that joy and freedom come only from the facing of life, the confronting of the difficulties. Sartre, when France was overrun by the Nazis, wrote a drama called The Flies. This is a retelling of the ancient Greek story of Orestes, and the little bit of it that I want to quote is that Zeus tries to get Orestes not to go back to his home town and kill his mother, which he was ordered to do to revenge his father. Zeus says, “I made you, so you must obey me.” And Orestes says, “You made me, but you blundered. You made me free.” And then Zeus gets quite angry, and he has the stars and the planets zooming around to show how powerful he is, and he says, “But do you realize how much despair lies ahead of you if you follow your course?” And Orestes says, “Human life begins on the far side of despair.” Now, I happen to believe that, that human joy begins — it’s like the alcoholics. They cannot get over the alcoholism except as they get into despair, and then the AA can take them and free them from alcoholism. That’s why I think despair has a constructive side, as well as anxiety having a constructive effect.

MISHLOVE: And you mentioned earlier the great artistic achievements of Mozart and Beethoven. One has a sense, where we even have this term, tears of joy — that when one experiences deep joy, it’s because it somehow incorporates the wholeness of human life, and we see the joy bubbling up, emerging through the despair itself. And that’s real joy.

MAY: Yes, yes, you have understood it very well.

MISHLOVE: And yet there’s something almost intimidating. It’s as if in many of us, as we live our lives and go through our routines, that we’re afraid to really drink deeply of the fullness of that.

MAY: Yes, I know. Well, if it were easy, it wouldn’t be effective. It’s not easy. Life is difficult, and I believe has many conflicts in it, many challenges. But it seems to me that without those life wouldn’t be interesting. The interest, the joy, the creativity, that comes from these is — say, in Beethoven’s symphonies: “Joyful, joyful, we adore thee.” That’s the end of the Ninth Symphony, and that “Joyful, joyful” comes only after the agony that is shown in the first part of that symphony. Now, I believe in life, and I believe in the joy of human existence, but these things cannot be experienced except as we also face the despair, also face the anxiety that every human being has to face if he lives with any creativity at all.

MISHLOVE: Rollo May, it’s been a pleasure being with you, and looking at this very deep issue of agony and ecstasy. I must admit that when I was reading your book Love and Will in preparation for this interview, I felt after reading the final chapter, almost waves of energy pulsing through my body.

MAY: Oh, marvelous.

MISHLOVE: Almost what the yogis would have described as kundalini. It was a very strange feeling of ecstasy and agony. It seemed as if your willingness to look so directly at life itself is almost a willingness to stare God in the face.

MAY: Well, that’s marvelous. I’m very happy that you had this experience.

MISHLOVE: Thank you so much for being with me.

MAY: It’s been a pleasure to be here.

MISHLOVE: Another concluding note — it makes me feel like in appreciating your work, I have a sense of why tragedy was considered the very highest art form in Shakespeare, for example.

MAY: By all means. The great plays were the tragedies. And in our day too — Death of a Salesman is one of the great plays of the twentieth century.

MISHLOVE: Rollo May, thank you very much for being with me.

MAY: Well, I enjoyed it myself.

END