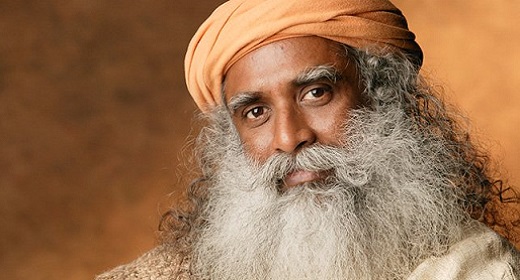

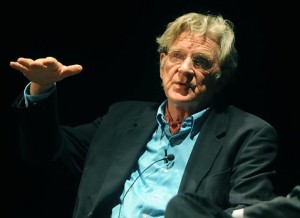

By David Bullard, Ph.D. The first American to have been ordained a Tibetan Buddhist monk, Robert A.F. Thurman, Ph.D., has been a personal friend of the Dalai Lama for over 40 years.

The New York Times has recognized him as “the leading American expert on Tibetan Buddhism” and Time Magazine named him as one of the “25 Most Influential Americans.” He is co-founder and president of Tibet House U.S., a non-profit organization dedicated to the preservation and promotion of Tibetan culture and civilization, and is president of the American Institute of Buddhist Studies.

The New York Times has recognized him as “the leading American expert on Tibetan Buddhism” and Time Magazine named him as one of the “25 Most Influential Americans.” He is co-founder and president of Tibet House U.S., a non-profit organization dedicated to the preservation and promotion of Tibetan culture and civilization, and is president of the American Institute of Buddhist Studies.

Dr. Thurman has translated many Sanskrit and Tibetan Buddhist texts, and is the author of 16 books on Tibet, Buddhism, art, politics and culture. Among his books are Circling the Sacred Mountain, Essential Tibetan Buddhism, Inner Revolution, The Tibetan Book of the Dead, Wisdom and Compassion: The Sacred Art of Tibet, Infinite Life: Awakening to the Bliss Within, Anger: Of The Seven Deadly Sins, The Jewel Tree of Tibet and, most recently, Why the Dalai Lama Matters.

He earned a Ph.D. from Harvard in Sanskrit Indian Studies, taught at Amherst College, and is now a professor of Indo-Tibetan Buddhist Studies at Columbia University. He lectures around the world, has a multitude of podcasts, and travels regularly to India, Thailand, Tibet, and Bhutan. When not traveling, he lives in New York City with his wife, Nena.

In 2005, I had the opportunity to travel with “Tenzin Bob” and fellow travelers on a two-week trip through the Himalayan Buddhist Kingdom (now democracy) of Bhutan, and during the years since have heard him interpret Tibetan Buddhist texts such as Lam Rim and the Vimalakīrti sutra in San Francisco, in New York City at Tibet House, and at Menla Mountain Retreat Center in upstate New York.

Bob and I spoke on August 14, 2010, at Menla, which also is known as The Land of the Healing Buddha, as one of the Dalai Lama’s Tibetan medicine healing centers. In a verdant valley setting – where the Dalai Lama says he had had his best night’s sleep outside of Dharamsala – Dr. Thurman and psychiatrist/author Mark Epstein, M.D. were conducting their popular summer workshop “Integrating Buddhism and Psychotherapy.”

David Bullard: Hello Tenzin Bob! Thank you so much for making time for this interview! To begin, here is a copy of neuropsychologist Richard Hanson’s new book, Buddha’s Brain –which he wanted you to have. Let’s start with some observations from the book: We each have about 1.1 trillion brain cells and 100 billion neurons, each of which fires up to 50 times per second and can possibly can be connected to 5,000 other neurons. Hanson says, doing the math, if you think of all those possible combinations and permutations of connections of 100 billion neurons each possibly connected to 5,000 others, you end up with 10 to the one-millionth different brain state possibilities. In contrast, the number of atoms in the physical universe is 10 to the 80th.

Tenzin Bob Thurman: Whoa – fabulous! That proves one thing – that brain size is equivalent to the universe, the Buddha-verse size, and that proves that our notion of the size of the universe is wrong – the ten to the 80th, is completely wrong. And just because they don’t see further and they think everything is running away – all the stars are red-shifting away – that’s just a mistake.

Beyond that is a barrier of darkness they think they can’t see beyond, so you can’t see all those millions of other universes. So you know the universe surely is the size of the brain, at least. The two are interconnected I’m sure, and the universe is in the brain. They are all interwoven – the Jewel Net of Indra they call it – the interpenetration of all things.

Anyway, that’s certainly the Cosmic Vision. We shouldn’t feel like we’re restricted to one miserable little universe that is only 10 to the 80th power!

DB: Bringing it back closer to home, at the personal level, you are married…

TBT: I have been married for 43 years to beautiful Nena.

DB: …and you have five children.

TBT: Yes, five children – that’s all-important – and five grandchildren. Actually four. One of them died, unfortunately.

DB: What a sadness for all of you! (pause) If this doesn’t feel too invasive, would you be willing to share some of your thoughts and feelings on this deep loss from your place as a Tibetan Buddhist?

TBT: Just let me say that it was an unfortunate accident that happened to a highly talented, wild and crazy guy, but the good thing is that he’ll be back!

Everyone loves him so much and he, them, he’s bound to reincarnate somewhere nearby any time soon – probably already has. It’ll be up to our visionary abilities as to whether we will recognize him or not!

DB: I also remember your kindness in Bhutan when I received a message that my elderly father-in-law had died. You acknowledged my sadness, but also encouraged me to imagine a rebirth: new muscles, ligaments, tendons and bones for someone who had struggled with severe arthritis. That was very helpful, even to someone not fully comfortable with these concepts. Thank you again.

Now, as an observer, I must say you are having quite a life this time around!

TBT: Well, I’m almost 70 years old now.

DB: The last time I checked you had 5,000 Facebook friends. (Note: By July 2011, he had almost 8,000.)

TBT: Well, that I don’t know. I’ve quit that because I couldn’t take care of it. I’m going try to get it going again, but I need an assistant who knows how to handle it. Otherwise, I disappoint people. I can’t respond or communicate with all of them; it’s too much activity.

DB: You brought up one of the most important words: disappointment. At the end of your and Dr. Mark Epstein’s workshop last year on integrating Buddhism and psychotherapy, you mentioned a comment your wife Nena made to you.

I bring it up here because when I think of you with five children – I only have two – it gives me pause. You have thousands of Facebook friends, while I have none, and that also gives me pause. Just the sheer number of readers and people who contact you – all that gives me pause!

Anyway, I recall that Nena told you: “Bob you are going to disappoint people, so you might as well do it sooner rather than later!”

TBT: Yes, she did!

DB: I told Nena today here at Menla that her comment was a great teaching for me. Others have also mentioned “disappointment” as a very deep Zen teaching. It is a great teacher. We might talk more about that a bit later.

Here’s something I’ve been wondering about: can you talk a bit about the difference between a guru in some spiritual traditions and a “spiritual friend” in the Tibetan tradition?

TBT: In most levels of Buddhism the authority and projection level of the mentor or teacher is de-emphasized because the burden is on the students to find things out for themselves, so the basic model of the spiritual teacher is that of a virtuous friend or auspicious friend, one who brings you good luck, and by giving teachings helps you gain knowledge and experience.

As a friend, he or she helps you on your way but you have to do it. It is important to remember the patriarchal context of Indian society. In traditional Indian knowledge fields the guru is a big authority figure – like a father figure – while there is a de-emphasizing of the father figure in most levels of Buddhism. In monastic Buddhism, the abbot is not a big boss and obedience is not a big virtue for the Buddhist monk or mendicant. In the Mahayana tradition, the spiritual friend is a teacher emphasizing how you have to get out there and do your own bodhisattva deeds and become a Buddha.

But in the Tantric and esoteric teachings, the guru figure – which in Tibetan is translated as the “Lama” – is brought back into play because in Tantra you’re dealing with the unconscious and you need someone upon whom to project different things to help you work out new relationships, like you do in psychotherapy. Also, there’s the initiatory practice of seeing the guru as the living embodiment of the Buddha when the teachings are transmitted to you.

The Tibetans have a proverb: “The best guru is one who lives at least three valleys away,” which means you receive the teaching and some initiatory consecration – and then you don’t hang out with that person to see how ordinary they are!

DB: You don’t meet once a week for 50 minutes?

TBT: No!….Well, that’s different, that’s psychotherapy. But you then can idealize them and see them as living Buddhas and remember what they did that day without having to “purify” your perception, where the ordinary things they do and ordinary interactions they have might make it difficult to see them as manifestations of Buddha. It’s not impossible, but it’s difficult.

I think that in the semi- or trans-parental relationship that the western therapist assumes with people, that clients or patients project upon them different things, and then the idea is to work out and improve their understanding of their relationships with their original figures – the parents – who are often messed-up, or appear so; you have a little bit of that in the Vajrayana.

But again, it’s not quite the same as recovering from being messed up. You could say it’s more like going into another dimension. The guru leads you; you have a rebirth with that guru, who becomes a new parent, and also in the Tantric and esoteric teachings you see the guru as indivisible from some divine Buddha deity figure usually, like a couple – a male and female in union.

DB: Let me jump to what you might like to say to Western psychotherapists. A recent count revealed there are 400 different forms of psychotherapy. Would you have any general comments on what you think they – we — are doing wrong, or are missing?

TBT: My general comment would be that I would hope they would resist the temptation or pressure – and I’m sure most of them do, actually – to define sanity and insanity in terms of our society as it is today. The ancient Buddhist understanding, which is also taught by people like St. Francis and in other spiritual traditions like the Sufis, is that the worldly person is insane, actually, from the point of view of the dharma person or spiritual person, while the spiritual person can be expected to be considered insane by the worldly person.

The worldly person lives for the purpose of this life. They want to get everything out of this life: get membership in this society, make their money, get their fame, get their status, have their relationships. That’s really what they’re living for.

The spiritual person is seeking to become an infinite being – to become the vast one – in the theistic tradition, becoming one with the divine, and in the Buddhist tradition to become a Buddha. Therefore, worldly success is defined in a different way: this life is seen as an evolutionary opportunity for you to evolve toward becoming an infinite being, and therefore you’re not that interested in the goals of status and success within the context just of this life. That becomes less interesting to you.

How this applies to people who do psychotherapy is that perhaps they should want to always think twice about whether whatever was unusual about the client and whatever might be thought of as deranged or neurotic – that that actually might be all used to that person’s spiritual advantage.

This would be in contrast to the idea that they should be reconditioned right away, given a spiritual Thorazine or a Librium, told to just cool down and accept that they are in this world and that this world is defined by our materialist society. I would encourage therapists to not just think of their job as re-socializing a person in a society that is really quite insane, our society where we are polluting and destroying the Earth, focusing on money and fame and everything to that end; as if there is no future existence, no future life, no heaven or hell, and “when you’re dead you’re just dead.”

That is not considered a healthy worldview from the perspective of the spiritual traditions or of Buddhism as a realistic tradition.

Psychotherapy traditionally has dealt with mental disorders and abnormal psychology. Buddhist psychology is more concerned with super-normal psychology: how to make people achieve extraordinary levels of happiness, of effectiveness, of kindness, and of love and joy and make contributions to their fellow human beings together with enjoying inner pleasure and even bliss. That’s sometimes achieved at the sacrifice of mundane glory or success like becoming wealthy or famous.

Sometimes the pursuit of those things goes against what I like to call the evolutionary life…. seeing life as an evolutionary sport. You’re taking things that happen to you to improve your evolution, to further your goal, which is to become an infinite being, a Buddha – one with infinity – one who, because of drawing from that infinity of energy, can be infinitely compassionate within a specific relationship at a very finite level – infinity including finitude.

So I hope therapists would not just seek to re-socialize people. The pressure is on them to do so, to give them some mood-altering drug to make them feel happy with themselves as ordinary people, and for them to function and hold a job to make a living. Well, in a way they’re forced to do that because we don’t have a monastic system here, we don’t have the generosity as a society to give people a free lunch when they’re seeking some sort of internal liberation or spiritual development.

But psychotherapists in a way are spiritual teachers in our culture. I think they should revise the unrealistic worldview of materialistic society when they are working with people. This current society is probably doomed; all the paradoxes and unhealthiness of the materialist ideology and industrial lifestyle are reaching their climax where they have become unsustainable. Therefore, psychotherapists are not doing people that big a favor by returning them to normalcy within this negative social matrix.

DB: I know you’re happy with the developments in Western psychology and psychiatry of “positive psychology.” For example, the “positivity” research of Barbara Fredrickson and Dacher Keltner, the learned hopefulness of Martin Seligman, Daniel Segal’s work, to name a few. A lot of people are going in this direction away from the pathological.

TBT: Yes, those developments all sound good.

DB: As for Buddhism and its many schools… if we took the Zen, Tibetan and the Theravada traditions…

TBT: …and there are different versions of each of those…

DB: If we generalize about those three main branches of Buddhism, is there something of value in each one that you think might appeal to the psychotherapist who was just beginning to explore Buddhist psychology?

TBT: Yes, I think there is. I have to say, however, that what we call Tibetan Buddhism is actually what I call the final form of Indian Buddhism, which was both university-based and monastery-based. Within a monastic university, there were monastics, celibates and renunciates but it was a highly educational system that incorporated all of the different methods developed for everyone, which included what is now known as the Theravada and Vajrayana, which included Chan and Zen. In China and Japan, Chan/Zen thrived in the cultural context of the Buddhist society as advanced meditation practices for people who grew up in Buddhism, knew about and respected bodhisattvas, learned from sutras, had Buddhist ethics and so forth. So it wasn’t just a single thing separate from Asian culture.

In the West it has been thought of as a unique single thing but it isn’t – it is basically Mahayana Buddhism, and the advanced meditative practice of it. The Tibetan Buddhist tradition brings to us all of those things and actually intersects and interacts very nicely with Zen and Theravada and other forms of Buddhism because it really fits them together with the other parts of the whole.

DB:And for those who want to begin meditation?

TBT:I think it is not as helpful for the beginner in our culture to just right away meditate when the educational element is not emphasized, when you don’t think anything, but just deal with some paradoxes with the teacher.

That can be unfortunate for beginners and it isn’t actually how you start Zen in Asia. Zen did come from India with 17 or 18 patriarchs, including Narjarjuna and others who themselves were university professors, and they are in the lineage of Zen. So Zen is like graduate school of an advanced, very focused meditative practice based on the practitioner already having gone through getting a high school diploma and a B.A., and all that growing up in a Buddhist culture. While I do love the colorful and inspiring examples of the great enlightened Zen people that is in their literature, to begin with that and right away think of practice as only sitting, and only sitting without discursive thought – I don’t think that is helpful to a beginner.

In the case of the Theravada Vipassana tradition – that’s a little better for a beginner. They go right into mindfulness, which is a form of self-awareness that is healing, on the way to transcendent wisdom, and very connected to psychotherapy. It is a little less potentially confusing than Zen, because it is a more basic and fundamental practice.

For Tibetan Buddhism, it isn’t that it’s Tibet – it’s that Tibet preserves those teachings. If you look at my book Essential Tibetan Buddhism and other historical works, there are three major phases of Buddhism in India: The monastic was the first, messianic was the second, and apocalyptic or esoteric was the third with 500-year increments. The monastic grew in Southeast Asia, although initially Sri Lanka had Mahayana and Vajrayana, so Sri Lankan Buddhists had the same synthesis that the Tibetans did up until the ninth century.

Then when Buddhism was destroyed in India, that synthesis was lost at the base and in Sri Lanka some very conservative monastics eliminated the rival monastery – that’s almost a recent thing that they got into, exclusively Theravada. For example, there were more Theravada Tibetan monks in Tibet, before China shut down Tibet, than in all the so-called Theravada countries combined, multiplied by five, in the sense that they held the Mulasarvastivada version of the Theravada vow, which is their monk’s vow.

There is another group of monastic Buddhists called Mahasanghikas. Some of the Chinese Buddhist monks have the Mahasanghika vow instead of the Theravada vow, but it is very similar to the Theravada. There is no Mahayana monk’s vow. The Mahayana bodhisattva does not need to be a monk; you can be a layman. My main point is that the Tibetan tradition preserves the synthesis of all of these different methods. It’s therefore a bigger drugstore for different kinds of people who need a different medicine – different paths are available to them.

It is true, on the other hand, in Tibet some of the paths have been less taught to lay people and so when the traditions meet in America, the reinforcement from Zen about doing certain types of advanced meditation and the reinforcement from the Vipassana tradition about getting right down to mindfulness practice—these are very good. And perhaps Tibetan Buddhism has reinforced the other traditions about the need for study to accompany the meditation practices. If only there was some reinforcement from somewhere to all American Buddhists to create and support monastic Sangha members, support the free lunch monks and nuns require, then all traditions would be much strengthened. We don’t really have that yet but in another 30 or 40 years, we will have a lot of American Buddhist monastics. Some of them will be from Burmese traditions, some from Sri Lankan, some from East Asian or Vietnamese, and some from Tibetan traditions. American Buddhist monks and nuns are very important.

DB:I’m thinking of the community of Thich Nhat Hanh.

RBT: Well, Thich Nhat Hanh is a wonderful and important teacher who emphasizes that we can’t dispense with the monastic or mendicant orders –we need them in American or Western Buddhism. Those are the people who really drop out and have to be taken care of by the generosity of our larger society. They are really only doing psychotherapy full-scale lifelong that becomes their yoga.

With the current economic climate for psychotherapy in America, because of the insurance laws and because of the whole economic pressure, it is unfortunate that mostly the only people who can really afford to do psychotherapy are wealthy people. It is their good karma to be wealthy from a Buddhist perspective because of their generosity in a previous life. Therefore they can use a psychotherapist as a type of spiritual mentor and carry on for a long period of time. So I think many psychotherapists’ long-term clients are wealthy.

Of course the laws should change so that insurance covers long-term care for people to be able to take that spiritual path. The fact that that is not the case at this time is not the fault of the psychotherapists or their clients. Right now, therapists can’t afford to provide therapy to everyone who wants it and many clients who want therapy can’t afford it. And the government doesn’t realize it’s really important.

The U.S. government is not like a Buddhist government, which most extremely existed in India, Tibet and Mongolia. You can’t really say East Asian countries were Buddhist countries. Buddhism existed there but the militarism, samurai, Shogun, and Chinese Emperor examples remained very strong. Buddhism was a counter-cultural thing in those societies, whereas in India and Sri Lanka until the 10th century, and in Tibet and Mongolia until the 20th, it was mainstream. There was much more Buddhist ideology, with the main aim of the entire country, people and government, being to support individuals in becoming infinite beings to whatever extent they could at that time.

In these Buddhist societies people genuinely seeking enlightenment would be honored and therefore they could be true mendicants and wouldn’t have to worry about livelihood, taxes and military service. They could just focus on enlightenment and self-analysis and on developing their wisdom and compassion.

In a way, psychotherapists may wish to consider themselves the vanguard of a new kind of society – a society that truly does value its individuals, where one individual’s development of psychological integration, compassion, emotional expansion, wisdom and insight to the nature of reality – that is the purpose of the whole shooting match.

As Dr. Spock from Star Trek would say, “It is all the all completely behind the one.” That’s the real ground level of it! We are all there for the one. The one is not demanded to be there for the all, but all are there for the one and therefore the one is never sacrificed for the all.

Luckily, the way it works out in Buddhist society – when the all are there for the one, and when many of the ones become as widely developed as they can be – when they are fully evolved, they naturally feel like being there for the all. They do not have to be forced. They want to be like bodhisattvas, they want to help the all, so it kind of feeds back in a positive way. Otherwise it seems impossible that the all can be there for the one. It becomes an impossibility, or an inconceivability.

DB: And maybe in between the all and the one, there is relationship. I’m curious as to your reactions to a quote from Kierkegaard…

TBT:. …Oh, a great, great Zen master….

DB: …Kierkegaard said this: “Perfect love means to love the one through whom one became unhappy.”

TBT: “…through whom one became unhappy?” That’s perfect love? Sure…That means “love thine enemy!” as Jesus recommended. For the enemy harms one, and that can make one unhappy. But if one has perfect love, one will want especially that enemy to be happy anyway. Whether or not one becomes unhappy at first when harmed, perfect love surely does mean complete and unflagging desire for the happiness of the beloved as the Buddha defined it, and that usually doesn’t make one unhappy, even if it’s unrequited. If it’s perfect love then one is happy just in the loving and in seeing and wishing and hoping for the happiness of the beloved. That brings happiness to the one. The Dalai Lama likes to say, “If you want to be successfully selfish, which means you want to be happy yourself, at least be wisely selfish, which means be unselfish, because being unselfish is what makes yourself happy and therefore fulfills your selfish interests.” It’s very paradoxical. Everything in life is very paradoxical, and that’s one of the most wonderful paradoxes in life. So Kierkegaard was a Dane and lived in a time of very uptight Scandinavian society – which all Scandinavians can testify to – with the valley of tears, the veil of suffering and sorrow, so naturally he might feel someone could or would make you unhappy by being your enemy, and he could see that love would need to be perfect to extend itself even to that enemy!

DB: Yes, and circling back to our beginning discussion of disappointment, another way to understand that passage comes from working with couples. They usually enter couples therapy convinced that they have been made unhappy by their partner, and can benefit greatly from recognizing the relative nature of who they are to each other, or the systemic aspects of their suffering, instead of two absolute beings each saying “I am this way and you are that way!” There is a kind of “instant karma” in that you tend to get back what

you have been presenting to the other.

TBT:In Buddhism, perfect love means maitreya Buddha, you know; maitreya means love…the loving Buddha…perfect love… the person who loves perfectly is always going to be happy no matter what happens to that person, that person will be happy.

DB: I’m feeling perfectly happy and loving this discussion, Bob! But I’m going to close with one more quote: This one is from the renowned Canadian novelist and poet Margaret Atwood that goes back to your suggestions about positive psychology and increasing our capacity for growth. She said “the Eskimos have 52 names for snow because it was important to them: there ought to be as many for love.”

TBT:That’s very true… I think that’s absolutely true…

DB:…and you’ve spoken of the many aspects of Tibetan Buddhism that speak deeply of love and relationships.

TBT:There’s a wonderful passage in the Vimalakirti sutra where he talks about the love of the bodhisattva and the love of the Buddha. To have perfect love, you actually have to be perfectly happy yourself; you have to be happy, since love is what wills the happiness of the beloved. If you don’t know yourself what happiness is, then how can you really be willing their happiness? You may be willing them to do something that you think might make them happy, but that won’t necessarily be what does make them happy.

When you yourself have a kind of reliable type of inner bliss awareness, a sense of connectedness to the universe where you feel the bliss of life flowing up and bubbling up within you, the bliss of freedom coming up within you, then you want others to have that. And that naturally overflows in the love that wants the beloved to be happy, because you realize happiness is everyone’s birthright. If you are really blissed-out like a Buddha, you see the bliss in the cells of the beloved and you realize it’s trapped from their own experience by some notion that they have: that bliss is not theirs, that they don’t have it, or someone is chasing them, and they live in fear. So your whole drive becomes to try to help them remove the blinders that have been placed on them by their experience, by their fear, by their culture, whatever notions they have that they are not allowed to be happy, not allowed to feel unreasoned and unreasonable bliss, and you then would do whatever it takes to free them. It doesn’t mean you would stare at them or smile at them or behave weirdly with them because that might freak them out even more. For a paranoiac – you can’t give him a hug or he’ll think you’re trying to smother him – you have to do a different kind of dance for a different type of person. But the person who is moved by bliss toward perfect love will come up with an effective dance, like mothers do with children. They will figure out that they’re hungry and what they need. For a mother who loves her child, that love will provide her with the intelligence and the skill to find out how to stop the problem.

DB:Thank you! This was a delight. It’s time for you to get ready to go back to the workshop in a half hour…

TBT:…it’s been my pleasure also… I’m glad you are doing this series of interviews for all these wonderful people.

I used to say – in giving lectures to Buddhist groups – that if people became enlightened in following the practices of Zen, Vipassana, Tibetan, whatever, they should combine their study of Buddhism with the study of psychotherapy and psychology, because the best livelihood in this society at this time for someone who gets a little bit of enlightenment would be to be a healer and a psychotherapist. This way they can help people in a sort of understood framework and relationship in context; otherwise they go back to do something that has nothing to do with sharing their enlightenment (though of course it would still radiate from them so it would be okay) or they try to become a professional guru and that has terrible problems associated with it. It is not really institutionalized in our society, it is something weird, and they are tempted to play guru games, and do all kinds of dumb things. They might go around thinking they are enlightened or pretending that they are… and it’s very hard for them. I’ve often told guru’s and lama’s this – while training your students for enlightenment, they can be building toward a livelihood where that enlightenment can be wielded altruistically for others in a socially accepted and understandable way: to live and help and be recognized as doing that without having to act like a guru. This would be much healthier for them. I’ve always said that.

DB: What an encouraging and positive ending to this interview. Thank you so much for your time, Tenzin Bob.

TBT: Heh heh….. Okay….good… Thank you, David.