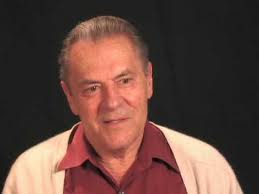

By Daniel Redwood Stanislav Grof, M.D., is one of this century’s pioneers in consciousness exploration. Born in Czechoslovakia, he came of age as an atheist in a Communist country, and was trained as a Freudian psychoanalyst.  In 1954, Sandoz Pharmaceutical Laboratories in Basel, Switzerland sent a sample of a newly-developed, little-known substance called lysergic acid diethylamide to the lab where Grof worked, with a request that they study it and report back their findings.

In 1954, Sandoz Pharmaceutical Laboratories in Basel, Switzerland sent a sample of a newly-developed, little-known substance called lysergic acid diethylamide to the lab where Grof worked, with a request that they study it and report back their findings.

Grof’s experience with LSD caused him to substantially reconfigure his worldview. Since that time, he has devoted his professional life to the exploration of non-ordinary states of consciousness, first with psychedelic substances and later with non-pharmacological means.

For years, he performed legal, government-sponsored research with psychedelics, exploring ways to utilize these substances in a psychotherapeutic setting. His book LSD Psychotherapy grew out of his work. He is a former Chief of Psychiatric Research at the Maryland Psychiatric Research Center, and is the author of over ninety professional articles and six books, including The Adventure of Self-Discovery and Beyond the Brain, and The Holotropic Mind. With his wife Christina, he co-authored The Stormy Search for the Self, and co-edited Spiritual Emergency.

His current work focuses on the use of non-drug methods for deep psycho-spiritual work. Stan and Christina Grof have developed a method called Holotropic Breathwork, which employs specialized breathing techniques, in conjunction with music designed to evoke deeper states.

DR: When you were growing up in Czechoslovakia, what first led you to pursue medicine, and in particular psychiatry?

Stan Grof: It was a very interesting thing. I never dreamt of becoming either a psychoanalyst or a physician, and I spent much of my later childhood and adolescence very, very involved and interested in art, and particularly in animated movies. Walt Disney was my great hero. Just before I graduated from high school, I had an interview to start working in the film studios in Prague. At that time, a friend lent me Freud’s Introductory Lectures in Psychoanalysis. I read it in basically one sitting, and it had a powerful impact. Within a couple of days, I decided that psychoanalysis was so interesting that I sacrificed my original plan for a career in animated movies. I decided to enroll in medical school. It was almost like a conversion experience.

DR: You started off as an orthodox Freudian, and you certainly aren’t one anymore. What profound event or events brought about the change in your worldview?

SG: I developed a very deep conflict within myself. As I became involved in psychoanalysis, and went deeper, I was more and more impressed with the theory of psychoanalysis. But then when I started seeing clients, I saw how narrow its range was, that not everybody could be considered a good candidate, and also that people must commit to doing it for a very long time. Three times, five times each week in the traditional framework, for a number of years. It was a great disappointment for me. And I have to say I regretted giving up animated movies.

Just at that time, I was working in the psychiatric department in the school of medicine in Prague. It was the beginning of the era of tranquilizers, and we were doing a big study on Mellaril, a tranquilizer manufactured by a company in Switzerland called Sandoz. They had also developed LSD, and since we were one of their clients, they sent us a complimentary sample so that we could work with it, and give them some reports as to what uses it might have.

DR: What year was this?

SG: 1954. I was still a medical student. I had to wait until I became a psychiatrist to have access, to have an experience. So I volunteered for an LSD session. It was such a powerful opening of my own unconscious that I temporarily became more interested in psychedelics than in psychoanalysis. It kind of overshadowed my interest in psychoanalysis. Later, I realized that LSD could possibly be used as a catalyst, that the two could be combined.

DR: It’s hard for most of us to imagine what it must have been like to take LSD for the first time in the mid-1950s, before all the publicity had led people to preconceived judgments about it. What were you expecting, and what happened?

SG: Well, I have to tell you, I kept a very detailed record of all my dreams. I believed that since this had something to do with the mind, that it would have to be understandable in Freudian terms. But what happened there was a level that was understandable in psychoanalytic terms, but then there was also this very, very powerful experience that was way beyond that.

DR: Is that something you can describe in words?

SG: What happened was that my preceptor was very interested in EEG [brain wave monitoring], and I had to commit myself to become a guinea pig in the middle of my session. I was wired up, and she was attempting something that called “driving the brain,” which meant that you would be exposed to a very strong stroboscopic, flashing light. The goal was to find out of the brainwaves would pick up the frequency that you were feeding to it. In relation to LSD, she was trying to find out how “driving the brain” was affected pharmacologically.

In the middle of my first LSD experiment, when I watched the flashing stroboscopic light, the nature of it all changed basically what happened was that I was catapulted out of my body. I first lost the laboratory, then I lost the clinic, then Prague, and then the planet. I had the sense that I was a disembodied consciousness of cosmic universal dimensions. I witnessed things that I would describe today as pulsars, quasars, the Big Bang, and expanding galaxies. While this was happening, the woman who was doing the experiment very carefully moved [the strobe light] through the different ranges of frequency -p; delta, theta, and alpha range, all carefully according to the research protocol.

When I came back to my body, I had a very intense curiosity about this experience. I tried to get hold of all the literature that was available. And psychedelics became part of my work.

DR: This was something you pursued while in Czechoslovakia, and later in the United States.

SG: I can say that since that time, in my professional career, I have done very little that is not in one way or another related to non-ordinary states of consciousness, with or without drugs. It is by far the most interesting area in the study of the human psyche.

DR: What would you say are the advantages of non-drug, and drug-induced, methods of psychospiritual work?

SG: I would say that it was a tremendously fortuitous thing that it came in the form of a substance, a pharmacological agent. That was pretty much the direction that psychiatric science was going at that time. We discovered the other dimensions -p; the spiritual, or what we call today the transpersonal dimension -p; as a kind of side effect of something that started as a psycho-pharmacological exploration of the brain

I became more and more interested in this, but it became much more complicated politically to work with psychedelics. This was because of the unsupervised experimentation with psychedelics, particularly among young people. So I became interested in similar states that are not produced by drugs. But had it not been for the fact that this opened up pharmacologically, I don’t think we would ever have studied these non-ordinary states. So my whole interest in finding some non-pharmacological way was inspired by what I had experienced with the psychedelics.

DR: What non-pharmacological methods did you gravitate toward first, and what has been the process through which you have developed your work?

SG: I would say that as long as I had easy access to psychedelics at the government-sponsored research project at Spring Grove in Baltimore [Maryland Psychiatric Research Center], most of my energy went into psychedelic sessions. I was also interested in near-death experiences, which are very powerful non-ordinary states, as well as various shamanic procedures, and meditation. [I have taken part in] ceremonies with North American and Mexican shamans, as well as Brazilian ceremonies

When I came to California in 1973 -p; I came first for a year -p; I was living at Esalen Institute. I decided to stay in California, and explore non-pharmacological methods. My wife and I developed holotropic breathwork, where the whole spectrum of psychedelic experience can be induced by very simple methods. You close your eyes, and breathe fast. It is enhanced by specially-chosen music.

DR: With holotropic breathwork, do some people access significantly deeper levels than others? If so, why?

SG: I would say that this is even true with psychedelics. There are some people who are quite resistant to psychedelics, while others have very powerful experiences at very small dosages. We know there are people who can start having very powerful experiences without anything, without taking psychedelics, without [holotropic] breathing. It can happen against their will. We call this “psychospiritual crisis” or “spiritual emergency.” This is a universal phenomenon.

DR: In some cultures, what you are calling a “spiritual emergency” is a recognized part of growth and individuation. In our culture, at least its symptoms are frequently considered pathological. How does our culture move in a more inclusive direction?

SG: My wife Christina and I have written a couple of books -p; one we wrote and the other we edited. We wrote The Stormy Search for the Self and edited Spiritual Emergency, which has articles by other people, pointing in the same direction.

The basic idea is that there exist spontaneous non-ordinary states that would in the west be seen and treated as psychosis, treated mostly by suppressive medication. But if we use the observations from the study of non-ordinary states, and also from other spiritual traditions, they should really be treated as crises of transformation, or crises of spiritual opening. Something that should really be supported rather than suppressed. If properly understood and properly supported, they are actually conducive to healing and transformation

DR: Who should and should not do holotropic breathwork?

SG: It’s not so much a matter of who should and who shouldn’t, but a matter of context We like to have people who don’t have a serious psychiatric history, for example a history of having been hospitalized It’s not a question of the holotropic breathwork itself, but if people really want to work on very serious problems, they should do it in an ongoing therapeutic relationship, rather than flying to another city where they have no connections, and then going home with no follow-up.

DR: So you feel follow-up is important?

SG: For someone who doesn’t have serious emotional problems, it may not be necessary, but if you are working with someone who is a borderline personality [according to the psychiatric definition], then this kind of work should be conducted in a setting with 24-hour supervision

DR: Do such facilities, with informed and caring staff, exist in this country?

SG: There are very few of them. For example, we have one here in California called Pocket Ranch, in Geyserville, about an hour north of San Francisco. A Jungian analyst, John Perry, has conducted two experiments, one called Diabasis, and the other called Chrysalis, near San Diego. Those are facilities where people who had these spontaneous episodes could go. Rather than being given tranquilizers, they were actually encouraged to experience fully what was happening to them. with the idea that they can get through it. One thing that is really missing is alternative facilities where people can come to be offered support rather than suppression DR: Can you give a general overview of the maps of consciousness that you have developed through your work?

SG: If you work with non-ordinary states, you will find out that if you systematically study the observations and the experiences, they would require very substantial revisions of our basic concepts of psychology and psychiatry

The traditional model that we have really takes into consideration only the body and the brain, which is the most critical for psychiatry. In terms of what in computer language we call software (the programs, the learning in the broadest sense), this model includes only postnatal biography. Freud said that we are born as a tabula rasa -p;- a clean state -p;- and that we become [what we are as] a function of the other, of mothering, of different events, various sexual problems, and so on. This is a model that simply is too superficial and inadequate.

I would add some very significant dimensions to it. The biographical domain is there, and it’s important, but it’s not all there is, particularly when we have more powerful ways of accessing the unconscious. There are two other domains, which I have called the “perinatal” and the “transpersonal.” The perinatal generally relates to the trauma of birth. There are now a number of techniques through which this can be experienced, such as primal therapy, rebirthing, and holotropic breathwork, as well as psychedelic sessions.

Then, beyond this is another level which we now call transpersonal. Here we find various mythological sequences, sequences from the lives of ancestors and the history of the race, and from past lives. Here we have many of the states described in spiritual literature, of cosmic consciousness, of the perennial philosophy. This map of the human psyche shows that each individual is an extension of all of existence. This supports what it says in the Upanishads. “Tat twam asi,” [which means] “You are it,” or “Thou art that.” This means in the last analysis that the psyche of the individual is commensurate with the totality of creative energy This requires a most radical revision of western psychology.

DR: With regard to holotropic breathwork workshops, what do you hope people can gain from it. Who should come?

SG: Are you talking about the lecture or the experiential part?

DR: Both, but particularly the experiential.

SG: I will be talking about the levels of non-ordinary states of consciousness, and in that sense I think it would be interesting not just for professionals -p; psychiatrists, psychologists, and psychotherapists, but also for theologians. and then because we all have a psyche, and it is very important to know ourselves, it would be worthwhile for intelligent laypeople.

In terms of the experiential part, it gives people a sense of what is possible in terms of deep self-exploration. It gives them a chance to get a taste of the holotropic breathwork. If it is something that they find useful, then they can pursue it on their own. Most of our energy these days is going into training people in holotropic breathwork. We have trained over 200 people, and 200 more are in training. These workshops are available now, in most areas of the United States.

Daniel Redwood is a chiropractor and writer who lives in Virginia Beach, Virginia. He is the author of A Time to Heal: How to Reap the Benefits of Holistic Health (A.R.E. Press), and is a member of the editorial board of the Journal of Alternative and Complementary Medicine. He can be reached by e-mail at Redwoods@infi.net.