by Alan Watts: My father and mother brought me up in a garden flutant with the song of birds, especially at dawn and twilight. They decided, however, that I should be educated as a Brahmin, an intellectual, directed towards the priestly, legal, or literary professions. As soon as I was exposed to the ideals of these disciplines, which were studious and bookish, I lost interest and energy for the work of the garden, though I remained enchanted with the flowers and fruits of other people’s work, so much so that in my old age I shall probably return to the craft of the garden, but of a very small garden, consisting mainly of culinary, medicinal, and psychedelic herbs, with nasturtiums, roses, and sweet peas around the edges.

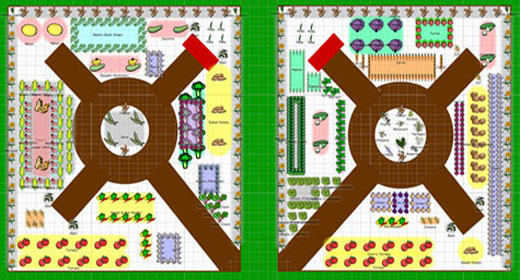

They decided, however, that I should be educated as a Brahmin, an intellectual, directed towards the priestly, legal, or literary professions. As soon as I was exposed to the ideals of these disciplines, which were studious and bookish, I lost interest and energy for the work of the garden, though I remained enchanted with the flowers and fruits of other people’s work, so much so that in my old age I shall probably return to the craft of the garden, but of a very small garden, consisting mainly of culinary, medicinal, and psychedelic herbs, with nasturtiums, roses, and sweet peas around the edges.

Alongside there will be a large redwood barn where the various herbs will hang from the beams to dry, where there will be shelves of mysterious jars containing cardamom, ginseng, ginger, marjoram, oregano, mint, thyme, pennyroyal, cannabis, henbane, mandrake, comfrey mugwort, and witch hazel, and where there will also be a combination of alchemist’s laboratory and kitchen. I can smell it coming.

The garden at home was what is now called “organic,” and, in my mind, I can still taste its peas, potatoes, scarlet-runner beans, and pippin apples which my father stored on wooden racks to last through the winter. (Having made recent tours of inspection, I can report that vegetables from this neighborhood are as good as ever.)

But the advantage of being a small child is that you can see vegetables better than adults. You don’t have to stoop down to them, and you can thus get lost in a forest of tomatoes, raspberries, and beans on sticks – and from this standpoint and attitude vegetables have nothing to do with the things served on plates in restaurants. The are glowing, luscious jewels, embodiments of emerald or amber or carnelian light, and are usually best when eaten raw and straight off the plant when you are alone, when no one can see you doing it, and when the whole affair is somewhat surreptitious.

This is, of course, what happened to Adam and Eve in the Garden of Eden, and perhaps it was an unripe apple that made Eve ill. It is not usually understood that she was a little girl and Adam a little boy, because they are always portrayed as mature adults, but they were obviously a couple of kids scrounging around Big Daddy’s garden. Having thoroughly satisfied themselves on gooseberries, raw peas, and green apples, they hid between the tomato plants and began to examine each other’s private parts. But just then Big Daddy came along and said, “God damn it, get the hell out of here, you bastards!”

One of the major taboos of our culture is against realizing that vegetables are intelligent – an insight which I owe to an inspired eccentric named Thaddeus Ashby, who haunts and dismays the general area of Southern California, but who is an undoubted genius. Not so long ago he arrived at my door in the rig of a British field marshal, Montgomery-style, except that the golden badge on his beret proved, on close inspection, to be a Buddhist emblem.

He explained that he was a true field marshal, representing the interests of the vegetable kingdom, and gave me a long discourse on the intellectuality, cunning, and compassion of the whole world of plants. This was in line with my own suspicion that every living and sentient being considers itself human – that is, as being at the center of the universe and as having attained the height of culture. He went into the amazingly beautiful and varied methods whereby plants disperse their seeds, and pointed out that fruit is sweet or tangy because the plants want to be eaten, so that seeds will be distributed through the alimentary canals of bugs, birds, or people.

He further exemplified our dim view of the plant world by the fact that we call decrepit people “mere vegetables” and deplore homosexuals by calling them “fruits.” He pointed out that, as distinct from mammals, birds, reptiles and fish, the brain and the sexual organs of plants are in the same place, and they do not therefore have the problems over which Freud puzzled, namely the conflict between the pleasure principle and the reality principle. He further suggested that the botanical world was so concerned about human misuse of the biosphere that it had decided to turn on us, psychedelically, so that we would come to our senses, or, if that wouldn’t work, to turn us off by making itself increasingly poisonous.

Now it is the papal infallibility and orthodox dogma of the present scientific establishment that plants are mechanisms without intelligence, and that they have neither feeling nor capacity for purposeful action. A little child hasn’t been told this, and therefore knows better. I knew that plants, moths, birds, and rabbits were people – as exemplified in such tales as The Wind in the Willows, Winnie the Pooh, and innumerable folk tales from all cultures.

Anthropologists and historians of religion dismiss this as animism, the most primitive, superstitious, and depraved of all those systems and beliefs which, in the course of historical progress, eventually blossom into Christianity or dialectical materialism. It is thus that our entire civilization has no respect for plants or for animals other than pets – the flattering dog, the wily cat, the obedient horse, and the mimicking parrot. It is high time to go back, or on, to animism and to cultivate good manners toward all sentient beings, including vegetables, and even lakes and mountains.