by Ralph Metzner: The discovery of psychedelics and the kind of time-limited, yet profoundly altered states of consciousness they induced has…

led to a significant re-examination and evaluation of all states of consciousness, both those ordinarily experienced by all, such as waking, sleeping and dreaming, and those less common, induced by such means as psychoactive drugs, hypnosis, shamanic drumming, certain kinds of breathing practices, and others.

We recognize some altered states as generally positive, healthy, expansive, and associated with increased knowledge and moral value: this would include religious or mystical experience, ecstasy (lit. “ex-stasis”), transcendence, hypnotherapeutic trance, creative inspiration, tantric erotic trance, shamanic journey, cosmic consciousness, samadhi, nirvana, satori. And there are others generally considered negative, unhealthy, contractive, associated with delusion, psychopathology, destructiveness and even crime, such as depression, rage, psychosis, madness, hysteria, mania, dissociative disorders, substance addictions (alcohol, narcotics, stimulants) and behavioral addictions and fixations (sexuality, violence, gambling, spending). The notion of “altered states” can be considered one paradigm for

the study of consciousness.

The research with psychedcatalysts could be certain foods, fasting, hypnotic inductions, sound, shamanic drumming, breathing (pranayama), trance dance, wilderness isolation, and so forth.

This hypothesis helps one to understand how it is possible that the very same

drug, e.g LSD, was studied and interpreted as a model psychosis (psychotomimeti

c), an adjunct to psychoanalysis (psycholytic), a treatment for addiction or

stimulus to creativity (psychedelic), facilitator of shamanic spiritual insight

(entheogenic); or even, as by the US Army and CIA, as a truth-serum type of

tool for obtaining secrets fom enemy spies. Of the two factors of set and

setting, set or intention is clearly primary, since the set ordinarily determines

what kind of setting one will choose for the experience.

In my classes on Altered States of Consciousness, I have extended the set and

setting hypothesis to all alterations of consciousness, no matter by what trigger

they are induced; and even those states that recur cyclically and regularly,

such as sleeping and waking (Metzner, 2005). In the sleep-waking cycle of

alterations of consciousness, internal biochemical events normally trigger the

transition to sleeping or waking consciousness; but external factors may provide

an additional catalyst. For example, lying in bed, in darkness, triggers

changes in melatonin levels in the pineal gland, which in turn triggers falling

asleep; and brighter light is normally the trigger for awakening, again meditated

by cyclical biochemical changes. There may be, in addition, external

factors such as stimulant or sedative drugs, or alarm clocks, which trigger

those alterations.

Clearly, the content of our dreams can be analyzed as a function of set, —

internal factors in our consciousness during the day, as well as the environment

in which we find ourselves. In fact, much of psychological dream interpretation

is based on the assumption that dreams ofen reflect symbolic processing

the prior day’s experiences, i.e. the intention. In dream incubation, a

form of divination, one makes deliberate use of that principle, consciously

formulating certain questions related to their inner process or outer situation,

as one enters the world of sleep dreaming. In hypnotherapy, as in any

form of psychotherapy, we always start with the intention or question that the

client brings, using that to direct the movement into and through the trance

state or the therapeutic session. In shamanic practice, whether with rhythmic

drumming as the catalyst, or entheogenic plant concoctions like ayahuasca as the

preferred method of the practitioner, one always comes initially with a question

or intention.

Even one’s experience in the ordinary waking state, such asthat of the reader perusing this essay, is a function of the internal factors ofintention or interest, and the setting where the reading is taking place. Some researchers, notably Stanislav Grof, in his cartography of altered states,whether induced by psychedelics or by holotropic breathing, have categorizedthe different states by content, such as perinatal memories, identifications

with animals or plants, experiences beyond the ordinary famework of time and

space, and so on.

Others, including myself, have taken a somewhat different

approach, focussing on the energetics of altered states, apart fom content. It

is possible to arrange different states of consciousness on a scale of arousal or

wakefulness, fom high excitement to sleep or coma; as well as a separate,

independent scale of pleasurable, heavenly states vs painful, hellish states

(Metzner, 2005).

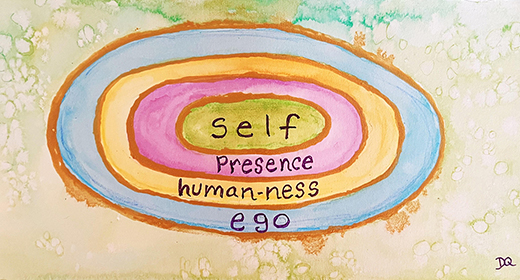

A third, purely formal or energetic, dimension of altered states, irrespective

of content, is expansion vs contraction. Psychedelic drugs were originally called

“consciouness-expanding”: in such states, one does not see hallucinated,

illusory objects; rather, one sees the ordinary objects but in addition sees,

knows and feels associated patterns and aspects that one was not aware of

before. In such states, in addition to perception, there is apperception – the

reflective awareness of the experiencing subject and understanding of associated

elements of context. Another way of saying this is that an objective observer

or witness consciousness is added to the subjective experiencing. This expanded

awareness, or apperception of context, is generally absent in the psychoactive

stimulants and depressants, which simply move consciousness either “up”

or “down” on the arousal dimension, and away fom pain or discomfort. The

observer witness consciousness is also notoriously absent in the addictive state

induced by narcotics, which is typically described as “uncaring”, “cloudy”, or

“sleep like”.

Returning for a moment to non-drug alterations of consciousness, we can see

that waking up, is an experience of expanded consciousness: I become aware of

the fact that it is I who is lying in this bed, in this room, having just had this

particular dream, and I become aware of the rest of the world outside, with all

my relations of family and work, community and cosmos. To transcend means to

“go beyond”; therefore transcendent experiences, variously referred to in the

spiritual traditions as enlightenment, awakening, ecstasy, liberation, mystical,

cosmic, revelation, all involve an expansion of consciousness, in which the

previous field of consciousness is not ignored or avoided, (we say, “that was

only a dream”), but included in a greater context, providing insight.

I have argued, in an essay on “Addiction and Transcendence as Altered States

of Consciousness” (Metzner, 1994) that while psychedelic and other forms of

transcendent experiences can be regarded as prototypical expansions of consciousness,

the prototypical contracted states of consciousness are found in

the fixations of addictions, obsessions, compulsions, and attachments. This

opposition between them is implied when psychedelic drugs such as LSD and

ibogaine are used in the treatment of alcoholism, drug addiction and other

forms of obsessional neurosis. For example, psilocybin, the extracted psychoactive

principle of the Mexican sacred mushroom, is now again being tested in

the treatment of OCD (obsessive-compulsive disorder).

Rituals Associated with Drug Consumption

I propose the following definition of ritual: Ritual is the purposive, conscious

arrangement of time, space, and action, according to specific intentions. In other words,

going back to the research with psychedelics, we could say rituals are the conscious

arrangement of set and setting. That’s why we had the different fameworks

that were used (psychotomimetic, hallucinogenic, psycholytic, psychedelic,

entheogenic) according to the predominant mind-set of the people

arranging the experience. The particular drug used, LSD, was the same, which

shows that the differing experiences were not due to different drug effects,

The consumption of our most popular psychoactive drugs, the depressant

alcohol, and the stimulant caffeine, is also surrounded by elaborate rituals, as

we know well: the cocktail party, the college beer party, or the ritual brewing

of the morning “wake-up” cup of coffee. Researchers in the field of heroin

addiction have found that the typical addict is as dependent on the elaborate

rituals of preparing for injection as he may be on the drug effect itself. Cigarette

smokers, and people watching movies of smokers, know well that the little

rituals of taking the cigarette out of the packet, the lighting of the cigarette,

for oneself or for others – all seem to be essential elements of the experience

that soothes anxiety, overcomes withdrawal distress, and strengthens the habit.

One can always ask – what is the intention behind the ritual ingestion? In the

case of cigarette smoking the intention appears to be to calm a stress reaction

and give oneself a reward.

Rituals of Everyday Life

We are all familiar with the common little rituals that punctuate transition

phases of our everyday existence. In the mornings we have the rituals of the

toilet and of cleaning, shaving, dressing and perhaps exercizing. At night time

we have the bedtime rituals of putting on night-clothes, stories, prayers,

good-night kisses. Parents with small children know how important it ofen is

to the child that the exact same sequence of ritual elements is preserved, in

order for the child to go peacefully to sleep.

The rituals associated with a family eating together are perhaps the oldest and

most venerable in human life, going back to the paleolithic times, when hominid

hunters brought back meat fom the hunt to share with the family and

tribe. We know as well the rituals of the family meal, and students of family

life have pointed out how important the family mealtime can be for the

strengthening the family bonds. Or how significant they can be for the development

of neurotic disturbances, especially eating disorders, where food

ingestion and sharing becomes laden with all kinds of extra emotional baggage,

and the taking of food nourishment becomes a substitute for missing emotional

nourishment.

It’s not so much the biochemistry of the food and drink that causes difficulties,

but the rituals of the family meal that come overlaid with hidden neurotic or

power agendas

.

Similarly, the activities of mating, sexuality, love, courtship, and marriage are

all connected with numerous complex ritual behaviors, some prescribed by

tradition and even religious teachings, others determined by glamorized

images in novels and films.

Students of the Indian traditions of Tantra and of the Chinese sexual teachings

of Taoism have re-introduced these ancient teachings into modern life

again – practices of ritualizing habitual sexual behavior and elevating to a

spiritual practice in its own right – rather than, as is ofen the case in Western

Christian-dominated societies, something that is contrary to spirituality.

Mircea Eliade, in his work on Yoga, referred to Tantra as “ritualized physiology.”

Institutionalized Rituals in Academia, Religion and the Military

Ritualized behavior in academic institutions like this university, are ubiquitous.

Typically, in collective ritual activities, there are clearly defined roles

for different people to play. For instance, there is the ritual known as the

“university lecture,” in which one group of people, called “students,” sit in a

more or less receptive mode, listening to an individual called “professor”

expounding on a selected topic. The two roles, speaker and audience, carry

differing but reciprocal intentions that bring them together into the same

setting, at the same time.

Human behavior in church, synagogue or temple is highly ritualized, so much

so that for many people the word “ritual” is synonymous with “religious

ritual”. Religious rituals, it has ofen been pointed out, can become seemingly

empty of meaning, just mechanical repetition of certain words, phrases and

gestures. What has happened here? It is when the original spirit or intention

behind the religious ritual – which undoubtedly had something to do with

connecting with divinity – is therapeutic “bedside manner” for successful therapeutic outcomes. The holistic medicine movement, in part inspired by Eastern medical traditions such as Chinese, Indian and Tibetan medicine, will consider all aspects of life-style,

including diet, exercise, emotional stress, family dynamics and even astrological

factors, as part of the overall picture of illness and recovery. These are all

aspects of the time and space arrangements, the set and the setting of the

interaction between physician and patient.

In the field of psychotherapy, the significance of the contextual ritual is also

well appreciated. Psychoanalysis was sometimes called the “talking cure”, but

actually, in the writings of Sigmund Freud and his successors, the psychoanalytic

healing ritual involved much more than talking. The psychoanalyst sits

behind the patient, who is lying on a couch; the latter is instructed to consider

the analyst a “blank screen” to which he can communicate his “fee associations”

— fee, that is, of the analysts potentially distracting appearance. One

of Freud’s most brilliant and innovative students, Wilhelm Reich, broke with

that tradition and invented his own very different therapeutic ritual: facing

the patient and observing the breathing movements of his body, he could

connect those to psychic content, reading the pattern of muscular tensions he

called the “character armor”.

More generally, the importance of a warm, comfortable, safe, aesthetically

pleasing setting and empathic manner of the therapist is widely appreciated.

These are all factors of ritual, believed to be and chosen to be conducive to

positive therapeutic outcomes.

If we compare how Western medicine and psychotherapy have incorporated

psychedelic substances into healing practice, with the shamanic healing ceremonies

involving entheogenic plant substances, a perception of the importance

of ritual is inescapable. The traditional shamanic ceremonial form involving

hallucinogenic plants is a carefully structured experience, in which a small

group (6 – 12) of people come together with respectful, spiritual attitude to

share a profound inner journey of healing and transformation, facilitated by

these powerful catalysts. A “journey” is the preferred metaphor in shamanistic

societies for what we call an “altered state of consciousness”.

There are three significant differences between shamanic entheogenic ceremonies

and the typical psychedelic psychotherapy. One is that the traditional

shamanic rituals involve very little or no talking among the participants, except

perhaps during a preparatory phase, or afer the experience to clarify the teachings

and visions received. The second is that singing, or the shaman’s singing,

is invariably considered essential to the success of the healing or divinatory

process. Furthermore, the singing typical in etheogenic rituals usually has a

fairly rapid beat, similar to the rhythmic pulse in shamanic drumming journeys

(widespread in shamanistic societies of the Northern Hemisphere in Asia,

Europe, and America). Psychically, the rhythmic chanting, like the drum pulse,

seems to give support for moving through the flow of visions and minimize the

likelihood of getting stuck in fightening or seductive experiences. The third

distinctive feature of traditional ceremonies is that they are almost always done

in darkness or low light, — which facilitates the emergence of visions. The

exception is the peyote ceremony, done around a fire (though also at night);

here participants may see visions as they stare into the fire.

I will briefly mention some of the variations on the traditional rituals involving

hallucinogens. In the peyote ceremonies of the Native American Church, in

North America, participants sit in a circle, in a tipi, on the ground, around a

blazing central fire. The ceremony goes all night and is conducted by a “roadman”,

with the assistance of a drummer, a firekeeper and a cedar-man (for

purification). A staff and rattle are passed around and participants sing the

peyote songs, which involve a rapid, rhythmic beat. The peyote ceremonies of

the Huichol Indians of Northern Mexico also take place around a fire, with

much singing and story-telling, afer the long group pilgrimage to find the rare

cactus.

The ceremonies of the San Pedro cactus, in the Andean regions, are sometimes

also done around a fire, with singing; but sometimes the curandero sets up an

altar, on which are placed different symbolic figurines and objects, representing

the light and dark spirits which one is likely to encounter.

The mushroom ceremonies (velada) of the Mazatec Indians of Mexico, involve

the participants sitting or lying in a very dark room, with only a small candle.

The healer, who may be a woman or a man, sings almost uninterruptedly,

throughout the night, weaving into her chants the names of Christian saints,

her spirit allies, and the spirits of the Earth, the elements, animals and

plants, the sky, the waters and the fire.

Traditional Amazonian Indian or mestizo ceremonies with ayahuasca also

involve a small group sitting in a circle, in semi-darkness, while the initiated

healers sing the songs (icaros), through which the healing and/or diagnosis

takes place. These songs also have a fairly rapid rhythmic pulse, which keeps

the flow of the experience moving along. Shamanic “sucking” methods of

extracting toxic psychic residues or sorcerous implants are sometimes used.

The ceremonies involving the Afican iboga plant, used by the Bwiti cult in

Gabon amd Zaïre, involve an altar with ancestral and deity images, and people

sitting on the floor with much chanting and some dancing. Ofen, there is a

mirror in the assembly room, in which the initiates may “see” their ancestral

spirits.

In comparing Western psychoactive-assisted psychotherapy with shamanic

entheogenic healing rituals, we can see that the role of an experienced guide

or therapist is equally central in both, and the importance of set (intention)

and setting is implicitly recognized and articulated into the forms of the

ritual. The underlying intention in both practices is healing and problem

resolution. Therapeutic results can occur with both approaches, though the

underlying paradigms of illness and treatment are completely different. The

two elements in the shamanic traditions that pose the most direct and radical

challenge to the accepted Western worldview are the existence of multiple

worlds and of spirit beings — such conceptions are considered completely

beyond the pale of both reason and science, though they are taken for granted

in the worldview of traditional shamanistic societies (Metzner, 1998).

It is worth mentioning that in the case of ayahuasca, there have grown in Brazil

three distinct syncretic religious movements or churches, that incorporate the

taking of ayahuasca into their religious ceremonies as the central sacrament.

Here the intention of the ritual is not so much healing or therapeutic insight,

as it is strengthening moral values and community bonds. The ceremonial

forms here resemble much more the rituals of worship in a church than they

resemble either a psychotherapist’s office or a shamanic healing session

(Metzner, 1999).

There are also several different kinds of set-and-setting rituals using hallucinogens

in the modern West, ranging fom the casual, recreational “tripping”

of a few fiends to “rave” events of hundreds or thousands, combining Ecstasy

(MDMA) with the continuous rhythmic pulse of techno music. My own research

has focussed on what might be called neo-shamanic medicine circles, which

represent a kind of hybrid of the psychotherapeutic and traditional shamanic

approaches. In the past twenty years or so I have been a participant and

observer in over one hundred such circle rituals, in both Europe and North

America, involving several hundred participants, many of them repeatedly.

Plant entheogens used in these circle rituals have included psilocybe mushrooms,

ayahuasca, san pedro cactus, iboga and others. My interest has focussed

on the nature of the psychospiritual transformation undergone by participants

in such circle rituals (Metzner, 1998).

In these hybrid therapeutic-shamanic circle rituals certain basic elements fom

traditional shamanic healing ceremonies are usually, though not always, kept

intact:

• the structure of a circle, with participants either sitting or lying;

• an altar in the center of the circle, or a fire in the center if outside;

• presence of an experienced elder or guide, sometimes with one or more

assistants;

• preference for low light, or semi-darkness; sometimes eye-shades are

used;

• use of music: drumming, rattling, singing or evocative recorded music;

• dedication of ritual space through invocation of spirits of four direc-

tions & elements;

• cultivation of a respectful, spiritual attitude.

Experienced entheogenic explorers understand the importance of set and

therefore devote considerable attention to clarifying their intentions with

respect to healing and divination. They also understand the importance of

setting and therefore devote considerable care to arranging a peaceful place

and time, filled with natural beauty and fee fom outside distractions or

interruptions.

Most of the participants in circles of this kind that I have observed were experienced

in one or more psychospiritual practices, including shamanic drum

journeying, Buddhist vipassana meditation, tantra yoga and holotropic breathwork

and most have experienced and/or practiced various forms of psychotherapy

and body-oriented therapy. The insights and learnings fom these practices

are woven by the participants into their work with the entheogenic medicines.

Participants tend to confirm that the entheogenic plant medicines, when

combined with meditative or therapeutic insight processes, function to amplify

awareness and sensitize perception, particularly amplifying somatic, emotional

and instinctual awareness.

Some variation of the talking staff or singing staff is ofen used in such ceremonies:

with this practice, which seems to have originated among the Indians of

the Pacific Northwest, and is also more generally now referred to as “council”,

only the person who has the circulating staff sings or speaks, and there is no

discussion, questioning or interpretation (as there might be in the usual

group psychotherapy formats). Some group sessions, however, involve minimal

or no interaction between the participants during the time of the expanded

state of consciousness.

In preparation for the circle ritual, there is usually a sharing of intentions

and purposes among the participants, as well as the practice of meditation, or

sometimes solo time in nature, or expressive arts modalities, such as drawing,

painting or journal work. Afer the circle ritual, sometimes the morning afer,

there is usually an integration practice of some kind, which may involve par-

ticipants sharing something of the lessons learned and to be applied in their

lives.

Rituals of Divination, Transition and Initiation

In both traditional and neo-shamanic practices and ceremonies, there are

really two main kinds of intention or purpose that are either implicit or ofen

explicitly recognized – i.e. healing or problem solving, which usually involve

dealing with the past; and seeking guidance or vision, which involve looking at

the future. One could say the overall purpose is divination – divination in

relationship to healing is called diagnosis or seeking the cause of the difficulty.

Western medicine and psychotherapy also looks to the past for understanding

the causal factors in illness or psychological difficulty: we ask where and how

did the wounding, germ, microbe, virus, infection, or familial relationship

difficulty begin? Shamanistic healers, for example in South America, are

likely, in about 50% of cases, to attribute the origin of both physical and

psychic disorders, to sorcery – so the question becomes by whom and how did

this hexing take place? Accurate causal diagnosis is recognized as being necessary

to determine appropriate and effective treatment or cure. (There are

exceptions to this practice: the most striking example is homeopathy, which

merely looks at the pattern of currently manifesting symptoms).

Divination of the future is not generally practiced in Western medicine or

psychiatry, except in the somewhat attenuated form that we call prognosis in

medicine.

However, academics, business people, and politicians in the modern world,

devote considerable energy and resources to determining future trends and

probabilities. Terms such as forecasting, scenario making, computer modeling,

trend projections – all indicate a profound interest in probable future possibilities.

Terms such as foresight and forethought are perhaps the terms most commonly

used to describe looking into the future. The profession of psychother-

apy has closed itself off fom looking into their clients’ future, largely, I

believe, because of an underlying belief that the future can’t be predicted. But

this rests on a confusion of foresight with prediction: people practicing future

guidance seeking to know the future is probabilistic, not determined, like the

past.

One of the ways the newly emerging profession of coaching is distinguishing

itself fom traditional psychotherapy by being more concerned with helping

clients clearly articulate their intentions for the future and helping them

realize them.

Among ordinary people in the Western industrialized nations and even more

in Third World countries, it is understood that divination is not like prediction,

and at the same time it is understood that the choices we make in the

present are greatly influential in bringing about the kind of future we envision.

For most people, the term “divination” is associated with systems such as

astrology, the I Ching, the Tarot, runes, stones, bones, etc. These may be

regarded as divination accessories or tools. If we examine the basic common

factor in all these methods is the asking of a question (or stating an intention)

which then guides the diviner’s or psychic’s attention and perception. Just as

the client’s question or intention determines the course of the psychotherapists

or physicians interventions. The practices that I have developed over the

past several years I call “alchemical divination” because their focus is on psychospiritual

transformation, as symbolized in alchemical language and symbolism.

They can be equally applied to past issues and questions of healing, as

well as future issues of seeking a vision or guidance for one’s life (Metzner,

2005). These practices are rituals, in their formalized structure of question-and-answer

processes, whether done with individuals or in groups. The

steps of the ritual, one might say, is purely internal, like a kind of meditation;

but the format is similar to what one would expect to see with a Tarot card

reader, or crystal ball gazer, or astrologer, where another, presumably neutral

person, who presumably is not as overanxious about some outcomes and, and

therefore “seeing” with more clarity and less bias.

There are certain differences in shamanic and alchemical divination practices

oriented toward the future, fom the kinds of approach to forecasting used by

futurists in academia or the business world. Whereas the latter use purely

rational, mental processes and statistics to anticipate future trends, shamanic

(and by extension alchemical, since alchemy is an outgrown of shamanism)

methods usually involve some kind of altered state method, to bring the questioner

and/or the diviner into an expanded or heightened state of consciousness,

also called “non-ordinary consciousness”, where they can glimpse into

the world beyond the here-and-now reality of the ordinary senses.

The seeking of guidance or a vision for one’s life was an essential core element

of the passages of adolescence in traditional societies, especially among native

North American Indians.

The Plains Indians, such as the Sioux, would have their young boys spend several days on a “vision quest” in the mountains or wilderness, fasting and praying for a vision for their life. There would be extensive preparation beforehand and integration aferward by a tribal or familial elder.

In recent years the practice of vision question or fasting alone

in the wilderness seeking a vision has been brought to many people at various

transition points in their life, not only adolescence – transitions such as

divorce, job changes, major deaths or losses in the family and so on. One seeks

to connect with inner sources of spiritual guidance, and ofen healing as well.

Rites of passage with a spiritual focus have for a long time been absent in the

modern world. They’ve been preserved only in very attenuated and simplistic

forms such as the rites of confirmation and bar mitzvah in religious communities,

which for many adolescents don’t carry much spiritual meaning anymore.

Or they may be found, also in greatly desacralized form, in college faternities,

and high school graduation ceremonies.

Or they may be found, for males especially, in the brutal violence of military boot-camp training, or of street-level gang initiations. Therefore, the re-introduction of such transition rites or rites of passage, like the vision quest. into modern society represents a

reconnection to the archaic life-wisdom practices of the ancient world and of

indigenous societies and as such presages the possibility of greatly deepened

community and social cohesiveness and health.

References

Metzner, Ralph (1994)

“Addiction and Transcendence as Altered States of Consciousness.” Journal

of Transpersonal Psychology, Vol. 26, No.1, 1-27.

Metzner, Ralph (1998)

“Hallucinogenic Drugs and Plants in Psychotherapy and Shamanism.” in

Journal of Psychoactive Drug. Vol 30 (4), 333-345.

Metzner, Ralph (1999)

“Introduction: Amazonian Vine of Visions” in Metzner, Ralph (ed) Ayahuasca

. New York: Thunder’s Mouth Press. pp 1-45.

Metzner, Ralph (2005)

“Psychedelic, Psychoactive and Addictive Drugs and States of Consciousness.”

in Earlywine, Mitch (ed.) Mind-Altering Drugs. Oxford University

Press, 2005. pp. 25-48.