A lecture by Kevin Langdon, October 15, 1986: The ideas I’ll be presenting tonight are intended for those who have understood that there is something fundamentally wrong with them as they find themselves to be and who feel an urgent need for change.

I am not speaking about people who are psychologically dependent and wish for someone else to give them a way to feel more comfortable, nor about those who attempt to lay blame for their situation on factors outside themselves.

I am not speaking about people who are psychologically dependent and wish for someone else to give them a way to feel more comfortable, nor about those who attempt to lay blame for their situation on factors outside themselves.

Instead, I am speaking of those who are commonly termed “spiritual seekers”–people who understand that they need something more than what they have been able to come to on their own and who are actively seeking help, in one way or another, to reach an understanding corresponding to their need.

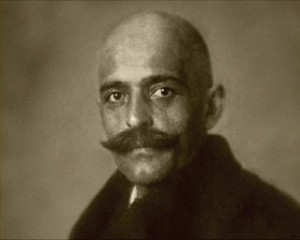

G.I. Gurdjieff was such a seeker from early childhood. Exposed to a great variety of Eastern and Western cultures as a boy, he was touched by mysteries which created in him a great hunger for knowledge. He organized expeditions through central Asia and the Middle East in search of schools where answers could be found to the questions that interested him.

The story of his search is told in his own book, Meetings with Remarkable Men. We do not have time to speak of it in detail tonight.

Gurdjieff began teaching in Russia in 1912 and subsequently established the center of his activities in Paris, working primarily with pupils from France, England, and America.

Gurdjieff brought a perspective which unites the disparate scales of our personal concerns, the life of humanity on the earth, and the cosmic scheme within which these and all other phenomena exist. His ideas provide a framework within which it is possible to think practically about one’s situation and the development of attention and consciousness and actually carry out a program of inner work to realize this development, under the guidance of someone who has carried out this program of work in himself, up to a certain stage.

Gurdjieff’s vision of the cosmic scheme places man within the film of organic life covering the earth, which is a part of the solar system, the Milky Way galaxy, and the universe of stars and galaxies as it is known to science, and sets all of this within a framework of intelligence consisting of cosmoses one within another, from God down to the tiniest speck of matter. Within this scheme, there is a perpetual flow of energy up and down; each level is fed by something and feeds something else, and the whole system is planned to remain in harmony.

According to Gurdjieff, organic life on earth is not a mere chance arising with no significance beyond itself but has a definite function in transmitting influences up and down the great chain of worlds.

A man serves nature whether he knows it or not, voluntarily or involuntarily, contributing his small share of energy to cosmic purposes of which he has no conception.

In the overall scheme, there is also a need for a small number of conscious beings to occupy a different place–to assist in harmonizing the creation through a work of service within the cosmic hierarchy. This possibility begins with a man’s relationship with a school where objective knowledge exists and is transmitted.

Such “esoteric” schools exist for those who see the importance of seeking something behind the veil of ordinary life concerns. As very few people are, have ever been, or are likely to become interested in anything less immediate than their next meal or their next conquest, such schools have never attracted large followings.

An esoteric school exists in accordance with cosmic purposes and not for the convenience of people who wish to be otherwise than as they have been created by nature. Man’s possibilities depend on forces beyond the scale of his life which are able to make use of him. In serving the higher, man also serves himself, becoming free from many laws which are otherwise obligatory and which keep him asleep and unaware of his actual position.

Gurdjieff taught that four states of consciousness are possible for man: ordinary sleep at night; the habitual hypnotized state in which people live when they get up and go about their daily lives (which Gurdjieff called “waking sleep”); self-consciousness, in which a man is awake to the whole of himself and sees himself as he is; and objective consciousness, in which he sees the reality behind the way the world appears.

In man as he is, self-consciousness appears only in rare flashes; objective consciousness does not exist for him. The two higher states of consciousness can be achieved on a more permanent basis only as the result of a prolonged work of self-study.

Man always identifies with what he sees, taking the focus of attention of the moment to be himself and forgetting the larger whole which is his real self.

Accordingly, an important place in Gurdjieff’s method of study, known by his pupils as “the work,” is occupied by attempts to divide the attention, reserving a portion for awareness of one’s existence, while placing the remaining attention on the phenomena at hand.

People always think that they are able to control their own lives and produce an outcome in accordance with their desires until they set themselves a serious aim–particularly one involving control over their own inner life–and try to achieve it. This effort produces a state of disappointment, as one cannot, in fact, do anything at all, and if results are achieved it is only through an accident of circumstances.

According to Gurdjieff, things happen in life as a result of influences originating at different levels of the universe, some of them far beyond the earth; nobody does anything.

Man is a complex machine, cleverly crafted by nature to be able to adapt to a great variety of circumstances, but in principle no different from an automobile, a radio, or a computer, except for the presence of certain possibilities of development which are quite unsuspected by the man himself, first of all because he does not understand that he does not possess a number of qualities he thinks he has. Most important among these are continuous consciousness, unity, and will, the ability to control the parts of himself and to act from himself rather than reacting from an identification with one side of himself.

If a man has not yet realized his helplessness in the face of life it means that he has never tried to do anything requiring real effort or that he is lying to himself about the results.

The most basic psychological need of human beings is for a sense of identity, but the most basic psychological fact is that people have no central “I” which is capable of maintaining dominion over their parts and regulating the harmonious work of the whole organism.

This fact has been overlooked in the West because, while Western culture places great importance on knowledge, it does not recognize that there is a complementary principle to knowledge, the principle of being.

A man’s level of being is the power of consciousness which determines the extent to which he is in possession of all that he contains within himself. Western man has almost no being, and thus he is unable to make practical use of his knowledge for his inner development. His knowledge remains theoretical and fragmented.

Understanding depends upon an equal development of knowledge and being.

In the absence of a real self, people invent one, not once but many times. The psychic state of the moment surveys its field of vision and sets up a momentary self-image, which is swept away as soon as the attention shifts.

This process cannot be halted just by wishing for it to stop, but one who has realized the illusoriness of the identities created in this way can cease to believe in them, at least at some moments.

Of course, to be present to oneself spinning fantastic dreams of being someone while knowing that one is not who one pretends to be is unpleasant, but it is preferable to continuing to lie to oneself, if one wishes to know the truth.

Gurdjieff likens our position to that of a man who has been imprisoned with no prospect for release. When he looks about him and realizes his position, he sees that his fellow prisoners do not understand that they are in prison and therefore have no inkling that any other possibility exists.

Such a man can wish for nothing else but to escape. But how can this be accomplished? A man must find a way by which escape is possible, and this can be done only with the help of others who have escaped before and know when the guards are not looking and where it is worthwhile digging. He also needs material help from those who have access to tools which are not available within the walls.

Those who are capable of helping others to escape are always deeply engaged in their own work and value their time very much. Therefore, instead of helping one man, they organize schools in which a number of people can be helped to develop the means to escape. When people work together they benefit from contact with one another–because their wish for liberation is strengthened by the exchange of experiences of inner work which takes place in a school, because it is often easier to see unpalatable truths in others than in oneself, and because the development and execution of a viable plan of escape is a large undertaking beyond the power of one man.

Schools come into existence in accordance with the aim of the teacher and exist only as long as they serve the purpose for which they are intended. Only the teacher fully understands his aim, but it is an important part of school work for the pupils to try to understand the aim of the teacher and find a way to be useful to him.

In a school, conditions are created in which the work of self-study which leads to inner transformation is facilitated through the presence of energies which awaken the wish of the pupil to realize his own latent possibilities.

These conditions typically include meetings where members of the school exchange ideas and observations regarding their attempts at self-observation, exercises for the attention, work on various projects with others in conditions organized by the teacher, and other forms which place the pupil in front of himself and demand sincere efforts to remain open to what he sees, rather than turning away from himself.

The pupil is expected at the same time to think for himself and accept nothing that he has not verified personally, and to obey the indications of the teacher; clearly, this is possible, beyond some preliminary experimentation, only when one has verified that the teacher knows one better than one knows oneself and that following one’s own opinions in these matters can actually retard one’s progress.

The prison in which man finds himself is one of hypnotic sleep. Man lives in a state of hypnosis and is vulnerable to every kind of suggestion, from other people in the present and the past, from literature and mass entertainment, and from the myriad voices in his head.

When a man realizes that he is hypnotized by everything his attention touches and is ready to believe anything that does not trigger an equally mechanical defensive reaction of disbelief, he begins to question whether there is any correspondence between reality and the way he thinks of the phenomena around him.

This questioning is very useful for a man who wishes for inner development, as it turns him toward direct experience as a guide to reality. Real knowing is direct, without any intervention of thought, but unless one values the rare moments in which one experiences the truth directly traces of them quickly become lost in the associative noise.

By the time he reaches adulthood, everything in a man’s inner world is arranged to keep him from seeing the truth about himself and his position.

He is shielded from seeing himself as he is through artificial appliances which Gurdjieff called “buffers,” which prevent him from feeling the contradictions which exist within him, as the buffers on a railroad car cushion the shocks when the train starts, stops, suddenly changes speed, or goes around a sharp curve.

In order to observe himself truthfully, a man must cease to be completely in the grip of buffers and confront the contradictions of his nature.

The conditions created in schools include shocks sufficiently strong that a man’s contradictions become accessible to observation. Naturally, being shocked is not pleasant, but intensive conditions containing major shocks are only provided to those who want them and whose preparation, in the opinion of the teacher, is sufficient that they can make use of them for inner work.

When a man sees the contradictions within him, a wish for being which is more than mental can arise through the awakening of conscience, which exists in man but is buried and whose call to him falls on deaf ears. He feels the warring sides of himself together and experiences the low level of his being and the wish to become different.

Conscience has nothing to do with the morality which is a part of man’s conditioning and which touches him only at the level of mechanical associations. It is a touchstone which unifies his disconnected parts and can lead to the development of his hidden possibilities.

Dependence on the indications of a teacher is a prolonged, but nonetheless temporary, stage in the Work. Sooner or later, through long and painstaking study, one must become able to make use of conscience as an inner guide, in order that one’s work may continue after the teacher is gone.

According to Gurdjieff, the categories commonly used by psychology, philosophy, and religion to represent the organization of man’s psyche confuse phenomena of different types and draw distinctions based on partial and incomplete observations.

Making use of these categories, various subjective theories, psychotherapeutic methods, and moral doctrines have been developed, on which people base their views of themselves and their attitudes toward the world around them.

Because these views are based on wrong divisions, they lead to nothing but the chaos we see everywhere in modern life.

Gurdjieff spoke of man as possessing both an essence, which is himself–the functions and inclinations he is born with–and a personality, which is composed of material assimilated from those around him: his parents, teachers, peers, the mass media, and other influences which reach him by chance or design.

A newborn baby is pure essence. During the first few years of life a child is bombarded with messages which indicate the expectations and demands of those around him. He is helpless and he has no choice but to adapt to these voices, either by conforming or by resisting; in either case, his view of who he is becomes more and more conditioned by outside influences.

In older children and adults, it is the personality which is active; essence, when it has not already died, is passive and participates to a relatively small extent in a man’s values, decisions, and reactions.

Essence and personality are intermixed in our experience of ourselves; it takes considerable study to begin to distinguish them reliably, but it is necessary to distinguish them, as essence is that in us which is capable of development while personality contains knowledge which is needed for the work to develop one’s possibilities as well as the principal obstacles to development.

It is reasonable to ask how one can begin to study one’s own structure without falling into the confining mold of the old categories. For this to take place, one must begin, very simply, by observing oneself as one is, in the situation of this moment.

But we do not know what it means to observe. It is not easy to watch what is taking place in oneself without believing in the constant stream of judgement and inner commentary which is produced by personality, and watching in this way can be done only for brief moments until one has accumulated more knowledge of oneself and of the many ways one identifies with and disappears into what one sees.

For this, sincerity with oneself is necessary, and sincerity is one of the qualities man believes he possesses when in fact he does not. In order to acquire sincerity, work in a group with a leader who understands the pitfalls of self-study and can help one to see the appropriation of every insight by the usurper in oneself that claims the place of the absent “I” is indispensible.

Observation must begin with the psychic functions in operation, in moments in which it is possible to see them simply and clearly and to assign what one sees to categories corresponding to the actual organization of the human machine.

When one observes, one sees at the same time elemental psychic functions which exist in essence and “content” manufactured by personality. Man ordinarily is immersed in and identified with the content of what he sees; everything has a meaning within a system of symbols which take the place of real experience of his existence.

Right observation involves making a separation between what appears in the moment and oneself. Although at first one has very little which can be taken as belonging to oneself–only the experience of “I am” in the moment–an effort of separation is possible which, at times, brings new impressions of oneself and eventually leads to the state of self-remembering, in which one is present to oneself in the moment through the force of the effort of separation.

In observing, one attempts to distinguish impressions of the various functions in operation, not through analysis but by taste. Each function has a distinctive signature.

Gurdjieff spoke of seven psychic “centers” in man, four of which are directly observable: the instinctive center, the moving center, the emotional center, and the intellectual center.

The instinctive center includes the senses, simple and complex reflexes, and the regenerative processes of the body that work without awareness at the cellular/biochemical level. All the functions of the instinctive center are inborn.

The moving center is responsible for the body’s perception of motion and for control of all impulses of movement. The functions of the moving center are learned through imitation and through early experimentation and adaptation.

The emotional center is responsible for all the varieties of emotional states, positive and negative, but the negative states arise only through mixing of the energy of the emotional center with the energy of the instinctive center. It is possible to develop an attention which is capable of discriminating among and separating these energies.

The intellectual center compares, calculates, and reasons.

The relative weight of the centers is not the same in the psychic life of different individuals. Gurdjieff spoke of three different types of men: man number one, in whom the moving and instinctive centers predominate; man number two, dominated by the emotional center; and man number three, in whose constitution the intellectual center takes the lead.

These centers, which Gurdjieff terms collectively the lower centers, because they operate with relatively coarse energies, work according to habits acquired over a lifetime and are generally not in balance with one another. They are lazy and do not want to do their proper work, borrowing energy from one another, which they are poorly adapted to use; they try to do one another’s work, which they are not designed to do and do not do efficiently or without undesirable side effects.

In addition to the tendency of the centers to shirk their own work and do the work of another center, they also exchange energy with the fifth center, the sex center, which works with a very fine energy corresponding to the subtle perceptions of which this center is capable. The sex center is much more difficult to observe than the four centers we have spoken of previously, due to the subtle energy which animates it.

The energy of the sex center, active in the lower centers, causes whatever work is undertaken to be done with a useless vehemence and intensity. The sex center, robbed of its own energy, is then coarse and sluggish.

Observation of this “wrong work of centers” occupies an important place in Gurdjieff’s method of self-observation.

In addition to the centers so far described, Gurdjieff speaks of two more centers in man, the higher emotional center and the higher intellectual center, fully developed and functioning, but cut off and inaccessible to man as he is due to the disharmony of the lower centers.

It is through the finer energies belonging to the higher centers that man is capable of realizing his highest possibilities and playing a conscious role in the administration of the universe.

Each of the lower centers is subdivided in several ways. We will speak briefly of one of those ways. Each center has an intellectual, an emotional, and a moving–or mechanical–part. The intellectual part works with consciously directed attention, the emotional part with attracted attention, and the moving part with distracted or dispersed attention.

In man as he is created by nature–whether number one, number two, or number three–the moving parts of centers predominate and produce aimless activity in which associations of a type corresponding to the particular center involved proceed randomly and his energy is wasted, producing nothing constructive for his being.

The mechanical part of the intellectual center has a special name: it is called the formatory apparatus, because, in the right functioning of the human machine, it is intended to set up forms for the higher parts of the center to operate upon.

In man as he is, the formatory apparatus has run wild and dominates psychic life. Its constant din of associations makes it almost impossible for a man to become quiet and observe himself as he is.

Because modern life is filled with formatory associations, even man number one and number two are often far from direct experience of their bodies and feelings. Consequently, a very important place in the Work is occupied by attention to the sensation of the body. This sensation is a stable point which can be of great help in developing sustained self-remembering.

In addition to man number one, number two, and number three, Gurdjieff spoke of four additional categories of man.

Man number one, man number two, and man number three all stand on the same level of being and all are equally mechanical.

Man number four is a man who has acquired a permanent center of gravity, consisting of his understanding and his valuation of the Work. He is no longer blown about by the wind, but refers everything to his aim of self-development.

Man number five is a man who has attained unity in himself. All his functions belong to the whole of him; nothing in him operates independently and without coordination. He possesses functions and powers which ordinary man does not possess, and he has crystalized an astral body, consisting of very fine energies, which is capable of surviving the death of the physical body.

Gurdjieff taught that immortality is a relative matter. The physical body dies and that is the end of it. The astral body can survive for some time after the death of the physcial body, then it also dies. But this is not the end of the matter; still higher bodies are possible.

Man number six has objective consciousness, powers beyond the powers of man number five, and a mental body. Man number seven possesses a causal body. Of course, we can have very little understanding of the meaning of these higher bodies, but full development of man’s possibilities lies in this direction.

If a man begins to work on himself seriously, sooner or later he will come to the conclusion that his energy is not sufficient for the efforts which are required.

While the work of self-study is difficult and demanding, there is enough energy in the machine as it is to begin to work on oneself. Eventually, in order to go further, more energy must become available for work, but work itself increases one’s energy, through capturing in the form of impressions energy that would otherwise be lost.

An important part in the work is also played by a struggle against certain manifestations through which very large quantities of energy are continually wasted. Principal among these manifestations are lying to oneself and others; useless and repetitious imagination about present and past, possible and impossible happenings, with or without any relationship to oneself; unnecessary talking; and giving expression to all kinds of negative emotional states.

The human organism is very complicated; attempts to change something in oneself usually give rise to unanticipated compensations in other parts which may be even worse than the situation one started out to change.

Struggling with the energy-wasting manifestations enumerated above is an exception to this rule; efforts of this kind do not result in unexpected and undesirable compensations in other areas.

To realize one’s possibilities, one must be practical and not be deceived by unrealistic expectations. One must especially not expect that one will be able to preserve every pet notion on the way to self-knowledge.

What is required for success in work on oneself is common sense, particularly about what is useful and what is not, willingness to engage in sustained hard work, and the ability to look beyond what one knows and actually take in new impressions in the moments when the energies appear that make this possible.

This work is for those who value the truth enough to relinquish their insistence that they know exactly who they are and what they’re doing at every moment, that their opinions carry the weight of revealed truth, and that their decisions are invariably for the best.

We are interested in your questions and your experiences, but we are not interested in your opinions. We are particularly not interested in hearing how you’ve managed to overcome all your problems and become satisfied with yourself.

I do not mean that we are opposed to your having your own opinions. Opinions are necessary; one does not always have the luxury of acting on anything more substantial. But opinions are necessary only when one must take action. To give your opinions a solid form and treat them as if they are more than tentative approaches to reality is to close yourself off from the possibility of experiencing anything new.

I’ve talked for a long time. Now you must decide whether to stay and listen and, perhaps, to work with us, or to go on your way and devote your time to something else.