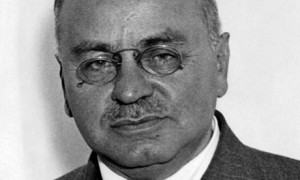

Alfred Adler did not write much about religion and spirituality. Other than referencing religion in a few of his writings, Adler wrote only one paper directly on religion.  This paper was written in collaboration with Ernst Jahn, a Lutheran pastor who wrote extensively on the integra- tion of psychology and Christian pedagogy (Vande Kemp, 2000). Jahn had also written comprehensive critiques of psychoanalysis (1927) and Adlerian psychology (1931). In 1932 he became acquainted with Adler, and the two decided to write a book on the care of souls and Individual Psychology.

This paper was written in collaboration with Ernst Jahn, a Lutheran pastor who wrote extensively on the integra- tion of psychology and Christian pedagogy (Vande Kemp, 2000). Jahn had also written comprehensive critiques of psychoanalysis (1927) and Adlerian psychology (1931). In 1932 he became acquainted with Adler, and the two decided to write a book on the care of souls and Individual Psychology.

Published in 1933, the book was soon seized by the Nazis and destroyed (Ellenberger, 1970). The book consisted of Jahn’s essay “The Psychotherapy of Christianity,” Adler’s essay “Religion and Indi- vidual Psychology,” and Jahn’s “Epilogue.” I will discuss Adler’s essay in chapter three.

Vande Kemp (2000) discussed Adler’s place in the integration move- ment and concluded that “Adler is only a minor figure in the psychology of religion” (p. 249). For example, in her review of the literature, Vande Kemp reported that her search of Religious and Theological Abstracts produced a mere 16 references to Adler, compared to 263 to Freud, 226 to Jung, 39 to Gordon Allport, and 22 to Carl Rogers. Furthermore, by 1984 Adler was mentioned as a significant figure in only 2 of 66 books on pastoral counseling in Vande Kemp’s annotated bibliography (Vande Kemp, 1984; 2000). She reported that Adler was discussed by Zahniser in his book The Soul Doctor (1938), in which Adlerian theory, along with Freud’s theories, were applied to case studies, and Cavanagh’s 1962 text, Fundamental Pastoral Counseling: Techniques and Psychology, in which Adler was included in the group of contemporary psychologists he criticized.

Wulff (1991), in his historical review of the psychology of religion, argued that Adler’s theories have received little notice in the literature. Though devoting full chapters to Freud, Jung, Erickson, and the object relation theorists, Wulff referred to Adler only as an influence on Victor Frankl and Theodore Schroeder.

Hood, Spilka, Hunsberger, and Gorsuch (1996) reviewed the empir- ical literature in the psychology of religion. Although they organized the conceptual and research information according to Adler’s life tasks, they made “no references to other contributions by Adler, nor to Individual Psychology as a school of thought” (Vande Kemp, 2000, p. 249).

Adler was, however, a strong influence on some theorists, i.e., May (1940); Nuttin (1950/1962); and Progoff (1956). Yet his influence on the psychology of religion movement has been small. Vande Kemp (2000) concluded that

Adler has had a significant influence on character education, a selective influence on the pastoral counseling movement, a negligible influence on the psychology of religion, and a minimal influence on psychology-theology integration. (p. 250)

As pointed out by Vande Kemp (2000), Adlerian psychologists and counselors have not contributed widely to the professional and academic literature on religion and psychology. However, Adlerians have discussed the issue of religion and spirituality among themselves for some time. Mansager and Rosen (2008) reported that their search of the literature resulted in 127 journal articles spread across 13 professional journals. The bulk of the articles were produced over the past two decades, but articles published as early as 1922 were reportedly found. The Journal of Individual Psychology, published by the North American Society of Adlerian Psychology (NASAP), has to date dedicated three issues to the topic of religion and spirituality. The first was a monograph published in 1971. Then in 1987, an entire issue was devoted to the topic of pastoral counseling. And finally the last issue to be devoted to religion and spiri- tuality in its entirety was published in 2000.

The broadening of Adler’s ideas on religion and spirituality began when Adlerians started to discuss spirituality as a life task. In the late 1960s Mosak and Dreikurs (1977/1967) argued that questions about the existence of God, immortality, and meaning were things every individual had to come to grips with. They asked the question: “Since the individ- ual’s relationship to the tasks of existence involve belief, conviction, and behavior, are these postures not also objects of psychological concern?” (p. 109). Their paper on the subject formed the basis for a discussion on religion and spirituality and spurred interests in these issues among Adle- rian writers.

Although Adler never specifically identified a spiritual task, Mosak and Dreikurs (1977/1967) argued that he alluded to it in his writings. Therefore, they determined that Adlerians should be talking about the spiritual task in addition to the tasks of love, work, and association. They went on to discuss five subtasks included in the spiritual task: the individ- ual’s relationship to God, what the individual does about religion, man’s place in the universe, issues around immortality and life after death, and the meaning of life. I will discuss the spiritual tasks as presented by Mosak and Dreikurs in more detail in chapter two.

However, it should be noted that some Adlerians have strongly argued against the addition of the spiritual task. Gold and Mansager (2000) concluded that Adler made no reference or allusions to other life tasks beyond the original three. They argued that Adler had a deep appreciation for spiritual mat- ters, however, and believed that religious and spiritual concerns were essential aspects of human life that Adlerians must attend to. It seems the addition of a spiritual task served to provide a context in which to discuss and address issues pertinent to religion, faith, and spirituality.

To conceptualize spirituality as a life task diminishes the significance and importance of spiritual experiences. Spirituality is more than a task that has to be dealt with, but rather an aspect of the human condition that may or may not be central to the original three tasks. For those who value religion and spirituality in their lives, spirituality can become a core aspect of work, love, and/or friendship. Thus, for these individuals spirituality becomes a central aspect around which life is organized. As such, it becomes part of everyday experiences. People may find the spiri- tual in their work, their relationship with those around them, in music, movies, sports, nature, and in every other human activity.

In their writings on religion and spirituality, Adlerian authors have addressed a variety of topics, such as the interface of spirituality and Individual Psychology, pastoral counseling (Baruth & Manning, 1987; Ecrement & Zarski, 1987; Huber, 1986; Mansager, 1987; 2000), the life tasks (Mosak & Dreikurs, 1977/1967; Gold & Mansager, 2000), the pro- cess of encouragement (Cheston, 2000), the political science of the Ten Commandments (Shulman, 2003), the “religious and spiritual problem” V-code (Mansager, 2002), and the interface of Individual Psychology and Christianity (Gregerson & Nelson, 1998; Jones and Butman, 1991; Kanz, 2001; Merler, 1998; Mosak, 1995, 1987; Newlon & Mansager, 1986; Saba, 1983; Savage, 1998; Watts, 1992; 2000), Judaism (Kaplan, 1984; Kaplan & Schoeneberg, 1987; Manaster, 2004; Rietveld, 2004; Weiss- Rosmarin, 1990), Buddhism (Croake & Rusk, 1980; Huber, 2000; Leak, Gardner, & Pounds, 1992; Noda, 2000; Sakin-Wolf, 2003), Confucian- ism (McGee, Huber, & Carter, 1983), Islam (Johansen, 2005), Hindu- ism (Reddy & Hanna, 1995), and Native American religions (Hunter & Sawyer, 2006; Kawulich & Curlette, 1998; Roberts, Harper, Tuttle-Eagle Bull, & Heideman-Provost, 1995/1998).

Excerpt from Religion and Spirituality in Psychotherapy by THOR JOHANSEN, PSYD