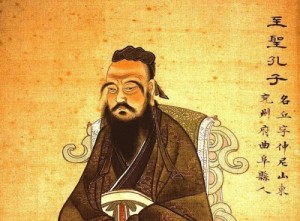

“The practice of right-living is deemed the highest, the practice of any other art lower. Complete virtue takes first place; the doing of anything else whatsoever is subordinate.” (Li Ki, bk. xvii., sect. iii., 5.)

These words from the “Li Ki” are the keynote of the sage’s teachings.

These words from the “Li Ki” are the keynote of the sage’s teachings.

Confucius sets before every man, as what he should strive for, his own improvement, the development of himself,—a task without surcease, until he shall “abide in the highest excellence.” This goal, albeit unattainable in the absolute, he must ever have before his vision, determined above all things to attain it, relatively, every moment of his life—that is, to “abide in the highest excellence” of which he is at the moment capable. So he says in “The Great Learning”: “What one should abide in being known, what should be aimed at is determined; upon this decision, unperturbed resolve is attained; to this succeeds tranquil poise; this affords opportunity for deliberate care; through such deliberation the goal is achieved.” (Text, v. 2.)

This speaks throughout of self-development, of that renunciation of worldly lusts which inspired the cry: “For what shall it profit a man if he shall gain the whole world and lose his own soul?”; but this is not left doubtful—for again in “The Great Learning” he says: “From the highest to the lowest, self-development must be deemed the root of all, by every man. When the root is neglected, it cannot be that what springs from it will be well-ordered.” (Text, v. 6, 7.)

Confucius taught that to pursue the art of life was possible for every man, all being of like passions and in more things like than different. He says: “By nature men are nearly alike; by practice, they get to be wide apart.” (Analects, bk. xvii., c. ii.)

Mencius put forward this idea continually, never more succinctly and aptly than in this: “All things are already complete in us.” (Bk. vii., pt. i., c. iv., 1.)

Mencius also announced that the advance of every man is independent of the power of others, as follows: “To advance a man or to stop his advance is beyond the power of other men.” (Bk. i., pt. ii., c. xvi., 3.)

It has already in these pages been quoted from the “Analects” that “the superior man learns in order to attain to the utmost of his principles.”

In the same book is reported this colloquy: “Tsze-loo asked ‘What constitutes the superior man?’ The Master said, ‘The cultivation of himself with reverential care’ ” (Analects, bk. xiv., c. xlv.); and in the “Doctrine of the Mean,” “When one cultivates to the utmost the capabilities of his nature and exercises them on the principle of reciprocity, he is not far from the path.” (C. xiii., 3.).

In “The Great Learning,” Confucius revealed the process, step by step, by which self-development is attained and by which it flows over into the common life to serve the state and to bless mankind.

“The ancients,” he said, “when they wished to exemplify illustrious virtue throughout the empire, first ordered well their states. Desiring to order well their states, they first regulated their families. Wishing to regulate their families, they first cultivated themselves. Wishing to cultivate themselves, they first rectified their purposes. Wishing to rectify their purposes, they first sought to think sincerely. Wishing to think sincerely, they first extended their knowledge as widely as possible. This they did by investigation of things.

“By investigation of things, their knowledge became extensive; their knowledge being extensive, their thoughts became sincere; their thoughts being sincere, their purposes were rectified; their purposes being rectified, they cultivated themselves; they being cultivated, their families were regulated; their families being regulated, their states were rightly governed; their states being rightly governed, the empire was thereby tranquil and prosperous.” (Text, 4, 5.)

Lest there be misunderstanding, it should be said that mere wealth is not to be considered the prosperity of which he speaks, but rather plenty and right-living. For there is the saying: “In a state, gain is not to be considered prosperity, but prosperity is found in righteousness.” (Great Learning, x., 23.) The distribution of wealth into mere livelihoods among the people is urged by Confucius as an essential to good government, for it is said in “The Great Learning”: “The concentration of wealth is the way to disperse the people, distributing it among them is the way to collect the people.” (X., 9.)

The order of development, therefore, Confucius set forth as follows:

Investigation of phenomena.

Learning.

Sincerity.

Rectitude of purpose.

Self-development.

Family discipline.

Local self-government.

Universal self-government.

The rules of conduct, mental, spiritual, in one’s inner life, in the family, in the state, and in society at large, which will lead to this self-development and beyond it, Confucius conceived to be of universal application, for it is said in the “Doctrine of the Mean” (c. xxviii., v. 3): “Now throughout the empire carriages all have wheels with the same tread, all writing is with the same characters, and for conduct there are the same rules.”

How this may be, is set forth in the same book (c. xii., v. 1, 2): “The path which the superior man follows extends far and wide, and yet is secret. Ordinary men and women, however ignorant, may meddle with the knowledge of it; yet, in its utmost reaches, there is that which even the sage does not discern. Ordinary men and women, however below the average standard of ability, can carry it into practice; yet, in its utmost reaches, there is that which even the sage is not able to carry into practice.”

It is, indeed, a true art of living which is thus presented, a scheme of adaptation of means to ends, of causes to produce their appropriate consequences, with clear and noble purposes in view, both as regards one’s own development and man’s, both as regards one’s own weal and the common weal.

For the completion of its work, it requires, also, the whole of life, every deflection from virtue marring by so much the perfection of the whole. Its saintliness lies not in purity alone, but in the rounded fulness of the well-planned and well-spent life, the more a thing of beauty if extended to extreme old age. Confucius thus modestly hints how slowly it develops at best, when he says: “At fifteen I had my mind bent on learning. At thirty I stood firm. At forty I was free from doubt. At fifty I knew the decrees of Heaven. At sixty my ear was an obedient organ for the reception of truth. At seventy I could follow what my heart desired without transgressing what was right.” (Analects, bk. ii., c. iv.)

That it is not finished until death rings down the curtain upon the last act, is shown in the “Analects” by this aphorism attributed to his disciple, Tsang: “The scholar may not be without breadth of mind and vigorous endurance. His burden is heavy and his course is long. Perfect virtue is the burden which he considers it his to sustain; is it not heavy? Only with death does his course stop; is it not long?” (Analects, bk. viii., c. vii.)