by Ram Dass: We can’t mask impurities for very long. When we suppress or repress them, they gain energy…

Eventually we all have to deal with our same old karmic obstacles. Maharaji used to enumerate them with regularity: kama, krodh, moha, lobh – lust, anger, confusion, and greed. It’s the spectrum of impulses and desires that condition our interior universe and our view of reality. We have to take care of this stuff, so we can climb the mountain without getting dragged back down.

This clearing out opens the door for dharma, for being in harmony with the laws of the universe on both a personal and social level. If you do your dharma, you do things that bring you closer to God. You bring yourself into harmony with the spiritual laws of the universe. Dharma is also translated as “righteousness,” although that evokes echoes of sin and damnation. It’s more a matter of clearing the decks to be able to do spiritual work on yourself.

The niyamas and yamas, the behavioral do’s and dont’s of Patanjali’s yoga system, are a functional approach to dharma that is useful without being judgmental. You do what will take you closer to God, the One, and don’t do what takes you further away. The dos, the niyamas, are: sauca, cleanliness or purity; santosha, contentment; tapas, austerity or religious fervor, swadhyaya, study; and ishwara pranidhana, surrender to God. Even the dont’s, the yamas, are framed as positive qualities to be cultivated: ahimsa, nonviolence or harmlessness; satya, truthfulness or nonlying; asteya, nonstealing; brahmacharya, continence or not being promiscuous, and aparigraha, noncovetousness or freedom from avarice.

There are many subtle issues surrounding these practices, of course, but those are the basics.

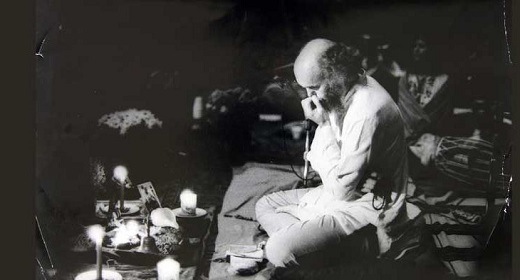

When I was first at the temple in the Himalayas, I was taught these practices by Hari Dass Baba, whom Maharaji assigned to teach me yoga. He wrote on a chalkboard, because he kept silence. He was very sweet, but the niyamas and yamas seemed like an almost Victorian moral code. As I learned more of yoga though, I began to see how these spiritual disciplines fit into the puzzle.

By the time I had practices the niyamas and yamas for six months, I felt much lighter. In my eyes I was beginning to become a true yogi. By directing my attention away from the distractions of the outer world, the niyamas and yamas were helping me to be more one-pointed in my inner journey.

This was a period of intense practice for me, in relative solitude in an ashram. But this stuff never really goes away. When I returned to the “marketplace” of the West, all the usual distractions were there.

Maybe they didn’t pull me quite as much, and I was no longer as completely fascinated by every desire. This is what the niyamas and yamas do – they create a perspective and help you focus on the deeper satisfaction from the spirit. For instance, brahmacharya, which is often translated, “celibacy,” actually means “linked to God.” You might be celibate, but it’s because you’re into God, not because there’s anything negative about sex. It gets subtle, and the work is ongoing. Even now, I am still wrestling with contentment in my old age.