Joan Halifax Roshi: A guide to allowing a gentle and meaningful death for our loved ones and for ourselves. by Joan Halifax: I GREW UP in the South, and one of the people I was closest to as a girl was my grandmother Bessie. I loved spending summers with her in Savannah, where she worked as a sculptor and artist, carving tombstones for local people. Bessie was a remarkable village woman; she often served her community as someone comfortable around illness and death, someone who would sit with dying friends.

by Joan Halifax: I GREW UP in the South, and one of the people I was closest to as a girl was my grandmother Bessie. I loved spending summers with her in Savannah, where she worked as a sculptor and artist, carving tombstones for local people. Bessie was a remarkable village woman; she often served her community as someone comfortable around illness and death, someone who would sit with dying friends.

And yet when she herself became ill, her own family could not offer her the same compassionate presence. My parents were good people, but like others of their generation, they had no preparation for being with her as she experienced her final days. When my grandmother suffered first from cancer and then had a stroke, she was put into a nursing home and left largely alone. And her death was long and hard.

This was in the early sixties, when the medical establishment treated dying, like giving birth, as an illness. Death was usually “handled” in a clinical setting outside the home. I visited Bessie in a plain, cavernous room in the nursing home, a room filled with beds of people who had all been effectively abandoned by their kin—and I can never forget hearing her beg my father to let her die, to help her die. She needed us to be present for her, and we withdrew in the face of her suffering.

When my grandmother finally died, I felt deep ambivalence, sorrow, and relief. I looked into her coffin in the funeral home, and saw that the terrible frustration that had marked her features was now gone. She seemed at last at peace. As I stood looking at her gentle face, I realized how much of her misery had been rooted in her family’s fear of death, including my own. At that moment, I made the commitment to practice being there for others as they died.

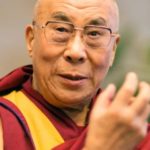

Although I had been raised Protestant, I turned to Buddhism not long after my grandmother’s death. Its teachings put my youthful suffering into perspective, and the message of the Buddha was clear and direct: Freedom from suffering lies within suffering itself, and it is up to each individual to find his or her own way. But Buddhism also suggests a path through our alienation and toward freedom. The Buddha taught that we should practice helping others while cultivating deep concentration, compassion, and wisdom. He further taught that enlightenment is not a mystical, transcendent experience but an ongoing process, calling for intimacy and transparency; and that suffering diminishes when confusion and fear change into openness and strength.

My grandmother’s death guided me into practicing medical anthropology in a big urban hospital in Dade County, Florida. Dying became a teacher for me, as I witnessed again and again how spiritual and psychological issues leap into sharp focus for those facing death. I discovered caregiving as a path, and as a school for unlearning the patterns of resistance so embedded in me and in my culture. Giving care, I learned, also enjoins us to be still, let go, listen, and be open to the unknown.

As I worked with dying people, caregivers, and others experiencing catastrophe, I practiced meditation to give my life a spine on which to hang my heart, and a view from which I could see beyond what I thought I knew. I was grateful to find that Buddhism offers many practices and insights for working skillfully and compassionately with suffering, pain, dying, failure, loss, and grief—the stuff of what St. John of the Cross has called “the lucky dark.” That great Christian saint recognized that suffering can be fortunate, because without it there is no possibility for maturation.

Through the millennia and across cultures, the fact of death has evoked fear and transcendence, practicality and spirituality. Neolithic grave sites and the cave paintings of Paleolithic peoples capture the mystery through bones, stones, bodies curled like fetuses, and images of death and trance on cave walls.

Even today, whether people live close to the earth or in high-rise apartments, death is a deep spring. For many of us, this spring has been parched of its mystery. And yet we have an intuition that a fragment of eternity within us is liberated at the time of death. This intuition calls us to bear witness—to apprehend a part of ourselves that has perhaps been hidden and silent.

Giving care to a dying person and his or her family is an extraordinary practice that puts one in the midst of the unknowable, the unpredictable, the breakdown of life. It is often something that we have to push against. Physical illness, weakness of mind and body, being in the crosshairs of the medical establishment, losing all that the dying person has worked to accumulate and preserve—all these issues can be part of the hard tide of dying. A caregiver can be there for all of that, as well as for the miracles and surprises of the human spirit. And she can learn and even be strengthened at every turn. As we give care, we can enter onto a real path of discovery—if only we let ourselves. Whether caregivers are family or professionals, they walk a path that is traceless, humbling, and often full of awe. And like it or not, most of us will find ourselves on it. We will accompany loved ones and others as they die.

If we are fortunate, we will be present for our own death. A dying person can meet the precious companions of truth, faith, and surrender. Grace and space can enter that person like a river flowing into the ocean or clouds disappearing into the sky. For practicing dying is also practicing living, if we can only realize it. The more truly we can see this, the better we can serve those who are actively dying and offer them our love without condition.