Ram Dass: by Alan Davidson: It is a glorious San Francisco day. I zip along the Golden Gate Bridge in a metallic blue Mustang convertible.  The sun warms my face and arms as the winter breeze whips around me, a delightful reprieve from the sultry humidity I’ve left behind in Houston. The San Francisco Bay shimmers in the sunlight. I pass Sausalito as the Mustang climbs into the hills of Marin County. I arrive at my destination early and park in front of a simple stucco cottage that seems out of place nestled into the surrounding upscale houses. There is a magnificent view of the bay. I feel a bit nervous. (Okay! Like majorly nervous.) I am here to have a conversation with Ram Dass for OutSmart. He is only one of the most influential and celebrated teachers of Eastern thought in America, and a huge hero of mine. I breathe in the freshness of the afternoon to relax and calm my mind.

The sun warms my face and arms as the winter breeze whips around me, a delightful reprieve from the sultry humidity I’ve left behind in Houston. The San Francisco Bay shimmers in the sunlight. I pass Sausalito as the Mustang climbs into the hills of Marin County. I arrive at my destination early and park in front of a simple stucco cottage that seems out of place nestled into the surrounding upscale houses. There is a magnificent view of the bay. I feel a bit nervous. (Okay! Like majorly nervous.) I am here to have a conversation with Ram Dass for OutSmart. He is only one of the most influential and celebrated teachers of Eastern thought in America, and a huge hero of mine. I breathe in the freshness of the afternoon to relax and calm my mind.

I remember the first time I heard of Ram Dass. I was bartending at the Montrose Mining Co. A rather peculiar customer made a musical request of our DJ, JD Arnold, which he complied with. The next night the customer brought JD a tip: a peyote button wrapped in a page from a book. The book was Be Here Now by Ram Dass.

Reading the page, I was so fascinated by the hallucinogenic scribblings of Hindu mysticism, Western psychology, and LSD trips that I went and bought the book. From Be Here Now I learned that Ram Dass was formerly Richard Alpert, Ph.D., a Harvard professor of psychology who had been fired–along with Timothy Leary–for wild experiments with LSD. (Ram Dass would reveal years later that his sexual escapades with his male students fueled the fires of the scandal.) However, Alpert became disillusioned with the ability of hallucinogenics to permanently change his life. When Aldus Huxley gave him a copy of The Tibetan Book of the Dead, Alpert recognized it as a map to greater consciousness. He set off for Asia in search of a guide to teach him to read the map.

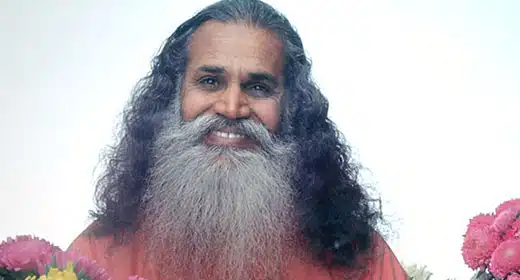

Alpert found his guru in India. He met Neem Karoli Baba in the foothills of the Himalayas. Alpert realized he had met a truly special human being the day Baba asked him about the tiny pieces of paper he was eating. “These are LSD,” Alpert responded. Baba replied, “Give me some.” Baba took 915 micrograms of LSD (the average dose is 50 to 70 micrograms). Alpert waited with interest for the outcome of the acid trip his teacher was about to have. Through the afternoon, with astonishment, Alpert noticed that the acid didn’t change Baba. Occasionally Baba would smile at him as he went through the business of the day. The LSD had no effect on him because Baba already lived in an expanded state of consciousness–he was already in the place that the drugs temporarily created for Alpert. Alpert knew then he had found the map-reader to teach him the mysteries he longed to understand.

Neem Karoli Baba taught Alpert Raja Yoga, a scientific system of transformation that was first written down around 500 B.C. This ancient system includes hatha yoga postures, meditation, the importance of diet on states of mind, understanding the deeper states of consciousness, and ahimsa (non-violence). After years of study Alpert was renamed Ram Dass, which means Servant of God, and instructed to return to the United States and teach what he had learned. Teach he did. Ram Dass became the premier teacher bridging Eastern mystical thought and Western psychology. His candor, his humor, and his rascally style endeared him to generations of Americans hungry for transformation. For a while after Be Here Now came out in 1971, it was the most popular book in English after Dr. Spock’s baby book and the Bible. In addition to teaching, Ram Dass’s long career includes the championing of environmental causes, hospice care for PWAs, and healthcare in impoverished countries.

Over the years Ram Dass has cautiously spoken about his relationships with men. In the early ’90s he moved from the East Coast to San Francisco, where he found that the liberal environment of Northern California helped him open up about his homosexuality. In 1994 he publicly revealed his gayness in an interview with Mark Thompson for Gay Soul. Despite this bold move, most people in the meditative communities who know of Ram Dass do not realize he is gay; and many in the gay community had never heard of Ram Dass.

Then, in 1997, at the age of 66, Ram Dass suffered a stroke, a massive cerebral hemorrhage he was not expected to live through. He was just finishing his latest book Still Here: Embracing Aging, Changing, and Dying. An active, healthy 66-year-old, he suddenly needed help doing the smallest tasks like walking, getting in and out of bed, or going to the bathroom. This dramatic and painful turn in his life gave him a new perspective on living in pain and what it’s like when you’re not expected to survive. He added a new last chapter to his just-finished book. And survive he has with his humor and candor intact.

I am here, now, looking across to Sausalito, waiting for my conversation and hoping I’ve enough composure to make complete sentences in the presence of one of the great minds and spiritual teachers of our generation. I take another deep breath, tear my eyes from the view, and walk to the bungalow.

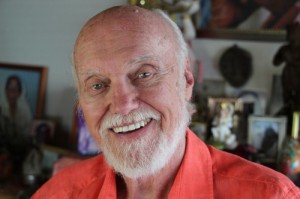

Andrea, one of his aides, lets me into a small living area, which is a little cluttered and sloppy. Stacks of paintings lean against the walls on each side of the fireplace. Pictures and statues of Hindu saints and gods appoint the room. To the right I see a study, and from inside it, Ram Dass is rolling his wheelchair toward me. He gently welcomes me and motions me to sit by his desk. There are pictures of his guru, Neem Karoli Baba, a picture of Timothy Leary, and a psychedelic portrait of Ram Dass done by Leary. The large window that frames his desk overlooks the water. Beyond an enormous cedar tree I can see the boat slips of Sausalito across the bay. He tells me that he spends much of his days here taking in the view. I can imagine him sitting here alone, when his fans and questioning reporters (or both, like myself) are no longer seeking his service, meditating on the rise and fall of the many moods of the bay.

Ram Dass is a big man. Confined to a wheelchair, he is still an imposing figure. His right arm and leg are paralyzed, and his right eye has a slight droop. He is wearing khaki pants, a polo shirt, and a yellow flannel overshirt. His wild hair is roughly combed and parted to the left. I am disappointed to see that he is wearing yellow-tinted glasses, for I have often heard descriptions of his blue eyes, reportedly so intense they can transfix an audience. His words are clear but the stroke has affected his ability to speak. “I have the concepts in my mind,” he tells me. “But the dressing room for the concepts [has been] harmed.” His speech is filled with long pauses and punctuated with false starts as he grasps for the right words. “Surf the silences with me,” he asks me. “The silences allow for a deeper connection.” His comfort with his speaking allows my own fears to relax.

I ask why Ram Dass has chosen at this late stage of the game to come out. He starts by telling me a story about his childhood. “When I was in prep school I was caught wrestling naked with one of my classmates. I was completely ostracized by the whole school. Nobody could talk to me. I was humiliated. Finally the captain of the swim team decided to be my friend. That was a very kind thing of him.” This prep school experience encapsulated a feeling of oppressiveness that he felt on the East Coast. “Harvard felt the same way,” he says. “Living out here [on the West Coast] is much more liberal.”

Also, he says he didn’t want people to be distracted from his message, to fixate on his sexuality and miss the truth he wanted to share. Contemplation of the nature of truth is a predominant theme in his life.

“Truth is a fine thing between people,” he says. “My life and my work have been about truth. All my life has been about teaching the truth. My homosexuality is the one thing I have not been truthful about. Now it is important to be honest.” I remember a quote by Mahatma Gandhi that Ram Dass is fond of using. Only God is truth. I am a human being. Truth for me is changing every day. My commitment must be to truth, not to consistency.

The conversation turns to his body, his recovery from the stroke, and living in a wheelchair. “Terrible grace,” he says of the experience. “The hardest part of this was my ‘loss of faith.’ For the first few weeks after the stroke I felt completely abandoned by God and my guru. How could this have happened to me? Now I see it as a gift.”

Before the stroke, Ram Dass describes himself as “fiercely” independent. Traveling, driving a sports car around town, teaching. He was always the teacher and caregiver. “Now I must accept care from others,” he says, which has led to a whole new path of insight.

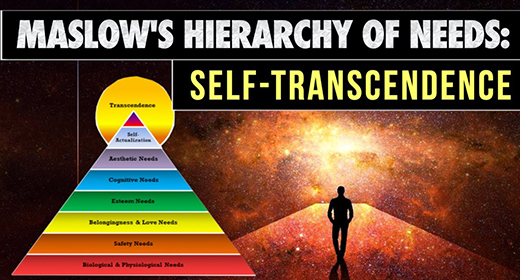

Ram Dass explains his view that there are three simple levels of consciousness. There’s the ego level where most human communication takes place, which is the level of the personality, our wants and needs. Second, there is the soul level where we connect with a broader perspective. “This is the level where the spirit is fed,” he says. “I like to call this level soul friends…. When I look at my stroke from the level of soul friends I can see a broader perspective. On the level of the ego I am being nursed and cared for by my aides. At the soul level I am learning to receive and they are learning to give. We are soul friends at that level.”

The third level is what he calls God consciousness, in which there are no boundaries. “This is the level that the great spiritual teachers speak of,” he says. “There’s no difference between me and the cedar tree out there, or the bay. I am all that is.”

I want to explore the distinctions between pain and suffering. I read a quote by Carl Jung: “Neurosis is the absence of legitimate suffering.” As I read, Ram Dass takes off his glasses to wipe his face. I see a flash of azure blue as his eyes focus on the view outside the window. He replaces his glasses and thinks about Jung’s quote.

“Pain is an inevitable part of life,” he says. “Spiritual practice teaches us to open to pain, to accept it as a part of life. Oursuffering comes from not accepting what’s happening in the moment, be it pain or pleasure or peace of mind–from trying to avoid the reality of life. Most of our suffering comes from that place where our personalities have separated from our true selves. We generate all kinds of neurosis to mask the pain and loneliness of that separation. Responding with care to a person in need is a beautiful thing. Sometimes people get caught in the ego-role as caregiver. They don’t feel valuable unless they can give you something. That’s a neurotic response to suffering.”

I remember a lecture Ram Dass gave once called “Service in the ’90s.” He spoke eloquently about the need for service in the world and his work with people with AIDS. He emphasized the importance of caregivers to be really present with the dying. Ram Dass described the window of healing that can take place when the caregiver is present at the level of “soul friend” and the ego of the dying person cracks open to a greater level of consciousness. He tells me another story.

“Some friends invited me to come visit a friend of theirs who was dying in the hospital. I came and was completely caught in the role of ‘Holy Man’ visiting the AIDS patient. My friends played it up and I was caught in my ego role. I visited with the patient and left. As I was leaving I thought to myself, ‘That wasn’t very much.’ I walked into the stairwell of the hospital and I prayed to God and my guru for a long time. I went back to that man’s room and we had a good visit human to human, soul to soul. That day changed the way I work with other people. Presence is the most valuable gift we can give another human being.”

Our talk turns to hallucinogenics. I read a quote of Timothy Leary’s in which he says that with LSD “spiritual ecstasy, religious revelation, and union with God were now directly accessible” to everyone. I ask Ram Dass what he thinks of hallucinogenics as a spiritual path. His eyes grow wide and he sits straight up in his wheelchair as he exclaims, “It is a fabulous path. Everyone should try it!” I laugh and tell him the story of the peyote button and my first introduction to his work. He laughs and says, “If you’d taken the peyote you wouldn’t have needed to buy my book.” On his website (www.ramdasstapes.org) there are photos of Ram Dass, sitting in his wheelchair on a mountaintop at the annual Rainbow Gathering. That’s the outdoor gathering of the hallucinogenic culture held in remote areas where LSD, psilocybin mushrooms, and pot fuel ’60s-style celebrations of God, Goddess, Mother Earth, and the joys of Love and humanness.

One concern of mine is the rise of fundamentalism in the world. To this Ram Dass replies, “Fundamentalism is one of the last stages of enlightenment.” I am so surprised to hear this (from my own place of spiritual superiority). He explains: If one is in this place of rigid righteousness that is fundamentalism and then falls, it “is so terribly humbling that it breaks open and frees the soul.” How should we respond to fundamentalism? “With our intuitive hearts,” he says. “Pull ourselves out of our egos and our spiritual roles and listen with care and compassion.” It is responding from this place that will begin to soften the hearts of the fundamentalists.

I ask about the future of the gay movement as he sees it. Ram Dass begins by saying that there is “still so much guilt and shame to be found in the gay community. And there are so many roles that gays get caught in…. As for the young gay kids coming out and growing up, I say this, ‘Don’t label yourselves. Allow your minds and your souls to connect with everyone you meet.’” Despite a lifetime of modeling a life of compassion and acceptence, Ram Dass says he still struggles at times with being open about being gay.

“I was standing in line at the adult movie theater once. I was in Chicago. And this hippie came walking by and saw me and recognized me. He stopped and started a conversation. As we talked I could see him registering where I was and his brain was scrambling to comprehend that Ram Dass, the spiritual teacher, was standing in line at the gay porn theater. In my mind I was trying to decide whether to be honest and go into the theater or to just walk down the street with him to get a cup of coffee. I chose to go into the theater. It took a lot of courage for me to do that. My own guilt and shame were so strong. It was the perfect opportunity for me to be here now!”

In his interview for Gay Soul, Ram Dass spoke of a longtime companion. I ask if they are still together. He answers candidly that he cannot talk about this relationship. He says, “I got into a lot of trouble for that interview. I choose to be open and honest about my life. When it affects others I must respect their privacy.”

What does he think two men need to cultivate as lovers to succeed with a life together? “Be soul friends,” he says. “All your differences happen at the level of the ego. If you focus on being soul friends then the tension and difficulties that life bring you will take care of themselves.”

We finish our conversation a few minutes early, and I summon my courage. I ask him, “Might I look into your eyes without your glasses?” He smiles, takes his glasses off, and turns toward me. I look deeply into his gaze. Melting is what I feel. My mind sharpens and slows. I breathe calmly. Some psychologists talk of body armor and personality. As I continue looking into Ram Dass’s eyes, I feel long-held tensions in my body and my mind relaxing. I feel a sense of peace I’ve rarely known. A flood of appreciation for this man and his kindness to me fills my heart. I bow silently. “I feel that I have been in the presence of greatness today,” I say. “Thank you.”

Ram Dass smiles and waves his hand toward the bay shimmering outside his window. “But we are in the presence of greatness every day,” he says.

As I make my exit I remember another of Gandhi’s quotes that Ram Dass is fond of using: My life is my message. Ram Dass has often said that he is an advance scout for his generation: first with psychedelics; then eastern mysticism and spiritual practice; and now aging. The grace, candor, and humor with which he lives his life are an impressive message indeed.