Ram Dass: by Michael McCarthy: “One time I had the opportunity to visit a mental asylum. I met a patient there who told me he was God.”  The speaker pauses for effect. The standing-room-only hall of 300 or so is silent, waiting for the next line. “I said to him: ‘So am I.’ He was quite upset because he wanted to be the only one.”

The speaker pauses for effect. The standing-room-only hall of 300 or so is silent, waiting for the next line. “I said to him: ‘So am I.’ He was quite upset because he wanted to be the only one.”

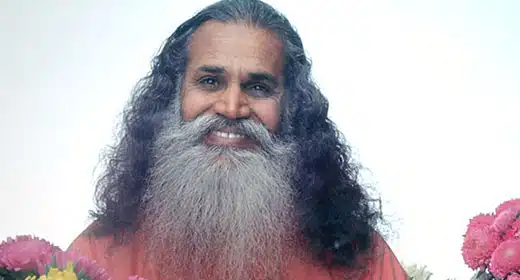

There is a sudden burst of laughter and applause. The timing of the phrase is perfect, the humor subtle and dry. The good guru is back. Ram Dass, aka Richard Alpert, ex-psychologist, one time hippie mystic, writer, world famous spiritual teacher, now 70 years old and confined to a wheelchair, is back on the lecture trail and his audience of new and old friends is loving every minute.

“You see, we all want to be God,” deadpans Ram Dass, “but the fact is we all are God.”

For close to 40 years Ram Dass has attracted international attention for his exploration of higher consciousness. His 1971 book “Be Here Now” was a major international bestseller. In February 1997, however, Ram Dass suffered a crippling stroke that left him with partial paralysis and a condition known as ‘expressive aphasia,’ a condition of the brain that interferes with the ability to speak and communicate. Imagine Muhammad Ali forced into silence by Parkinson’s Syndrome and you have some idea of the irony surrounding the return of Ram Dass to the public eye. Can he still talk? Is he brain-damaged? What revelations can he possibly share that he hasn’t shared before?

“Ram, as you may know, means Messenger of God,” he says slowly, the words followed by a long silence, “but in my case it’s also an acronym for Rent A Mouth. It means you rent my mouth to hear things you already know. There was a guru once who used to give lectures in silence.” Another pause. “I bet you’d be really ticked off if I did that.”

The crowd howls again. The white-haired old man in a wheelchair may not be the bushy-bearded, velvet-tongued psychedelic pioneer of the early 70s, but it’s clear he’s still got some chops. Wearing a faded jean jacket, ball cap, and cool shades he still looks good although clearly aged from the photos adorning the cover of his latest book. More importantly, perhaps, to an audience of old hippies, new agers, and seekers-after-enlightenment gathered this cold and clear night Ram Dass still has some vital life lessons still to share. If a journey of a thousand leagues begins with a single step, much of this crowd has already made a few hairpin turns and is jostling for parking space near the Pearly Gates. But aging and dying, says Ram Dass, are no cause for fear at all. On the contrary, life is but a garden to be wandered and savored. Just don’t forget to stop and smell the flowers. Be here now! “Before I had my stroke I played the cello and enjoyed golf and drove my little MG with a stick shift. After my stroke I saw very clearly that if you had an attachment to the past you would suffer. So now I am an ex-golfer. People say he has taken his stroke well. I recommend that you take all the strokes of life well.” Another pause as the audience soaks up the teaching, then “People push me around now in my wheelchair. Wow, you should see me move through airports these days.”

Far from his public reputation as an ancient relic from the “flower power generation,” Ram Dass clearly has a modern message that flows throughout his latest writings and teachings. “Still Here,” his recent book and the basis for his current public tour, deals with the concept of “conscious dying,” certainly a topic that should be of interest to the great wave of aging American baby boomers surging towards retirement and old age. But like “Be Here Now,” whose main message might best be described as “awareness is next to Godliness,” his latest foray into higher consciousness require some reflection for a generation obsessed with staying young. What does he mean? Aging is ugly, illnesses and injuries are to be avoided at all costs and death is the ultimate insult to the body beautiful. What’s to celebrate in that?

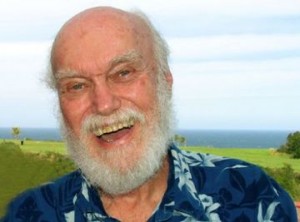

“He’s always been a little ahead of the curve,” says Don Lattin, religion editor for the San Francisco Chronicle. Author of Shopping For Faith, Lattin has been following Ram Dass’ career since the 1980s. “He was certainly one of the most influential spiritual teachers of his generation, but he never built himself his own little empire, unlike some. I call him a ‘consciousness explorer.’ One time I met him in a drugstore, appropriately enough, and he said: ‘Please don’t call me a sixties icon Don; nobody wants to talk to an icon!'”

“As the baby boomers grow old he has managed to still ‘be there’ because he has been doing work on aging and dying for quite some time now,” says Lattin. “A lot of it was tied into the AIDS epidemic in the 80s. Some of his early sixties stuff looks a little silly these days, but it’s really his service work that should be remembered.”

“I used to visit people in the gay community who were dying of AIDS,” says Ram Dass “and people would say: ‘Ok, Ram Dass is here now, so I can die.’ I would go into my spiritual role and say something about the afterlife, as if I know anything about it. But that was because I was in my ego and I saw him in his role as a patient. After a while, I started to visit people as a ‘soul,’ and then you see them in a different light. All I had to do was envision myself as a soul, and my mind became a mirror for him to see himself.”

Although his mind is quite clear, Ram Dass speaks very slowly these days and only in short paragraphs, illustrating his thoughts through brief teachings. According to his physicians, after such a major stroke it’s amazing that he’s even alive, never mind speaking coherently or remembering thoughts sequentially. However, in typical Ram Dass fashion he has managed to look upon his “illness” as a stroke of good luck.

“It’s like you have this dressing room in your head,” he says. “All the words are hanging up there like clothes, and you take them off and then put them on one by one. I no longer inhabit a wordy universe. In fact, it seems funny even to be talking about silence. Maharaji taught that suffering brought him closer to God. I have only one motive – I am using this stroke to get myself closer to God.”

Mahariji, as Ram Dass speaks of him, is Neem Karoli Baba, his personal teacher or guru, whom he met in 1967 while on a trip to India. Although Maharaji departed for the astral plane many years ago, Ram Dass still speaks of him in the present tense.

“When I first met Neem Karoli Baba I drove 100 miles through the jungle. The night before I met him we camped out and I went out to have a pee. I’m out there under a thousand stars and I started to think about my mother who had died, and the Freudian part of me started to wonder about that connection. The next day when we met, he told me all about my mother, how she had died from complications from the spleen, that she was in a higher place. How he could know about her I don’t know. You see, he was in my mind even before I met him. He is here now.”

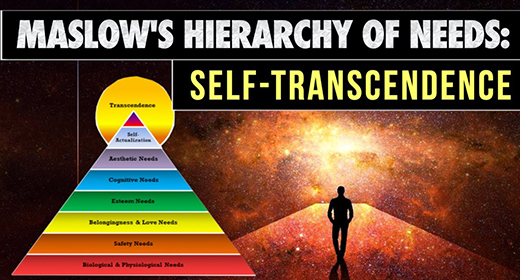

There are three levels, or perceptions of consciousness, explains Ram Dass. The first is ego, the second is the soul and the third is nirvana. They all share the same plane, and it is possible to be conscious of all three at the same time. Ego is the software for the administration of the plane, and the soul is the witness of the plane. The word “spiritual” means having two planes going at one time, but you can surf all three at the same time if you practice detachment.

“When I had my stroke, the ego was shattered. It was in pain. I lost my faith for awhile. That was the real suffering. Then my soul took over,” explains Ram Dass. “My ego said: ‘Help! Chaos! Pain!’ But my soul was simply a witness and said: ‘What’s this? A new chapter? How interesting!’ My soul found the stroke was enjoyable as good entertainment. All sorts of interesting stuff going on! Doctors, nurses! Everyone took it so seriously!”

Again the pause for effect. “Well, you know how people are.” The battle against ego has been a constant theme throughout Ram Dass work, going back to his earlier incarnation as Richard Alpert. Born in 1931 to a wealthy father who founded Brandeis University and the New York and New Hartford Railroad, Richard studied psychology and personality development, receiving degrees from Wesleyan University and Stanford University. He taught at Stanford and then at Harvard University from 1958 to 1963. It was at Harvard that he met fellow consciousness explorer Timothy Leary in 1961. The rest, as they say, is history.

In collaboration with Leary, Ralph Metzner, and Aldous Huxley, Alpert intensively researched and experimented with LSD-25, psilocybin and other consciousness-expanding hallucinogens. At that time, the psychotropic qualities of these particular substances were totally unknown. When the true nature of their work into human consciousness became public, embarrassed administrators of Harvard University fired Leary and Alpert.

“I was a grad student of theirs at the time,” says Metzner, now a Sonoma resident who teaches at the California Institute of Integral Studies in San Francisco and has just published a book about “ayahausca,” a lliana vine from the Amazon said to induce telepathic states. “It was Leary who started taking psilocyben mushrooms as part of a study on creativity with convicts. There were no models in those days to copy. You can’t study human consciousness in any other way; you must take the drugs yourself. It’s like a microscope that changes the perceptual focus of the scientist. Then drugs became a sensation and it started turning into a social movement. But I don’t think Ram Dass was a messenger of the sixties at all; it’s more like the seventies, when he brought eastern and western thought together.”

While being fired from Harvard might well have spelled the end of any academic’s career, for Alpert it was only the beginning. He traveled to India, where he met Neem Karoli who bestowed the honorific Ram Dass upon him.

Since 1968 he has studied guru kripa, devotional yoga focused on the Hindu spirit Hanuman; meditation in Theravadin, Mahayana Tibetan and Zen karma yoga; and Sufi and Jewish studies. In 1974 he founded the Hanuman Foundation, whose work includes the Prison Project, assisting prison inmates during their incarceration; and the Dying Project, a support structure for conscious dying. He co-founded the Seva Foundation, an international service organization; he’s been prominent in the environmental movement and with the Social Venture Network, an organization working to bring social consciousness into business practices. He has written eight books, including this year’s Still Here: Embracing Aging, Changing and Dying, “an invitation for everyone to break through our perspectives on aging and to reinvent our roles as elders.”

“I was with my father when he died,” he says. “He was in his 90s. During our lives we had two monstrous egos and we fought all the time. Then during the dying we shifted our roles. We were no longer father and son but just two souls. One goes ahead, the other doesn’t. I now see that aging – conscious aging – carries the person from the ego to the soul.” “We souls have all been sitting around the campfire for thousands of years, trying to figure out what to do with ourselves. Nowadays we are all trying to figure out George W. Bush,” he chuckles. “One moment you were a rock, then a diva, then you came into this incarnation. Dive down deep into yourself and take this incarnation seriously. Not as an ego, but as a witness to it all. That way you get the nectar out of your incarnation.”

From Ram Dass’ front window on a hill above Richardson Bay in Tiburon, the sun sets over Mt. Tamalpais. It’s a modest cottage, as befitting its owner, with posters, pictures, artifacts and the collected memories of a lifetime scattered about.

Ram Dass likes to sit quietly here in the window behind his cluttered desk and watch the water ripple in silence. After a lifetime of exploring, learning and talking, it’s to a silent place that he has finally come, to bask in the winter warmth and to meditate on a life of sharing and giving.

“Before I got sick, I gave. I gave and gave. I gave my time, my wisdom and my money. I gave to the blind and to the poor. But then I got sick and I started to have huge medical bills and my friends gave to me so much,” he says, slowly. “It’s been harder for me to learn to receive than to give. I don’t like the word ‘giving’ so much. It has a slight power. Sharing is better, it’s about being equal.”

The words come slowly, painfully, as he looks out into the setting sun and struggles to put sentences together.

“Experience teaches you that holding on to things is not much fun. If that thing is money it cuts you off from other people. The attachment or aversion to ‘things’ is what is distracting. Aversion and attachment are much the same,” he pauses. “I used to say to people: ‘Here, I am giving this back to you, because I want it.’ Desire is the problem.”

“In our culture, the shopping mall has become the church,” he continues. “All of this giving at Christmas, I think, is not so much with Christ. It’s unfortunate that his message is taking people in a worldly direction. His message of giving had nothing to with material things; it had to do with self. Christmas is all about giving people things that they want, and that is desire.”

He turns from the sun steaming in the window, a silver halo framing his face, and beams a huge smile. Behind him, above the desk, is a framed photo of his guru, laughing. In his left hand – his good hand – he holds a statue of Hanuman, the laughing, impish monkey god. “When I was a child, the best thing I ever got was my parent’s love, but the best gift I was ever given in my life was when Neem Karoli Baba made me realize I could obtain liberation and peace.”

Fog is wafting off the water in warmth of the late afternoon and a silver glow shines in, framing his weathered face. On the beach below ducks and sandpipers dabble in the mud of an ebb tide. Seagulls drift overhead; a soft breeze stirs the trees.

“Those of us who are aging have memory problems. But you know what? That’s just a clue that you don’t need that memory anymore,” he laughs. “Souls don’t have memories, they live only in the present. Ego is what can’t stand a memory loss. Soul is only a moment, being in the moment. Keep in the soul, and you will meet so many interesting people.”

Film on Ram Dass Due This Spring

Fierce Grace, a film about Ram Dass including old rare footage, is nearing completion and should make its premiere in Marin this spring if final sources of funding can be found.

“We’re pretty close to ‘locking picture,’ with just a little editing to be done,” says Linda Maroney, associate producer for Lemle Films. “We don’t have a distributor yet because we still need to secure funding for marketing and promotion, but we’d like to launch the film next spring in San Rafael, if possible.”

Fierce Grace, 93 minutes, starts with Ram Dass talking about his recent stroke, and retraces his life through his early days in Boston, Harvard, Millbrook and then on to India. The producers even traveled to Neem Charoli Baba’s old ashram, but most of the film is recent footage.

“We could have made a 10 part series, there was so much material available, and it’s been difficult getting 60 hours down to 90 minutes,” says Maroney. “But we simply didn’t have the money for that.”

“The film is really a window onto the larger cultural theme of our era. With his experience of dealing with the reality of aging and illness, Ram Dass continues to offer wisdom to a generation that thought it would remain forever young,” says producer and director Mickey Lemle. “For example, he demonstrates that physical adversity and emotional suffering can provide a profound opportunity for spiritual growth.”

To date, all funding for the film has been provided by friends and foundation grants. Tax deductible donations can be made to Film Odyssey, 132 W 31st Street, NY, 10001. For more information call Lemlepix at 212-736-9606.

Meanwhile, Ram Dass continues to speak at events in the Bay Area and around the world.

“He will be speaking at a weekly series of Sunday programs starting in January at Spirit Rock,” says Marlene Roeder, his personal secretary. “When he had the stroke, the doctor’s gave him a 10 per cent chance of living but the level of his recovery has been fantastic. His memory is excellent, but he has trouble with some words.”

Michael McCarthy is a Canadian print and broadcast journalist currently living in Marin County, California where he writes cover stories for the Pacific Sun, the second oldest alternative newspaper in America. While living in Vancouver, Canada, Michael was founder, editor and publisher of Spare Change, one of the world’s first “street newspapers.” For his work raising consciousness about urgent social issues and putting millions of dollars into the pockets of homeless people, Michael was awarded the prestigious Ethics in Action Award in 1996 by Canadian Businesses for Social Responsibility. Michael interviewed Ram Dass as part of a book he is writing called Discovering Atlantis, an “inner and outer journey” into the Bay Area, its history and the people who have made San Francisco such an extraordinary place.