Ocean Robbins: Welcome to this Food Revolution Conversation. I am Ocean Robbins, your host…

We’re here to talk today about inflammation, and we’re going to talk about it a little more comprehensively than most people talk about it these days.

Chronic inflammation could be, in net effect, the leading cause of death on our planet. It is underlying most of the major chronic illnesses of our times, from Alzheimers to type 2 diabetes from cancer to heart disease to autoimmune conditions.

In the context of a pandemic, we’ve also seen that people who are suffering from chronic inflammation are far more likely to be hospitalized and even to die if they contract COVID-19.

And according to our guests for today’s conversation, the chronic inflammation that is rampant in the human body is inextricably linked to a surge in inflammation in our world, showing up in the context of climate chaos, forest fires, and even war and violence.

What’s more, these have common sources. According to their new book, Inflamed: Deep Medicine and the Anatomy of Injustice — an extraordinary book — there are hidden relationships between our biological systems and the profound injustices of our political and economic systems.

The Roots of Inflammation

Ocean Robbins: Inflammation is connected to the food we eat, the air we breathe, and the microbes living inside us, which impact our brains, our immune system, and how we experience life.

Inflammation is also connected to traumatic events we may have experienced as children and to traumas even endured by our ancestors. It’s connected not only to access to healthcare, but to the very models of health that physicians practice.

So, we are here with two extraordinary people who have written this book and who are here to shed some light on all of this.

First is Dr. Rupa Marya, a physician, and activist, a mother, and a composer. She is an associate professor of medicine at the University of California San Francisco where she practices and teaches internal medicine.

She’s co-founder of the Do No Harm Coalition. It’s a collective of health workers committed to addressing disease through structural change. At the invitation of Lakota health leaders, she is helping set up the Mni Wiconi Clinic. I may be mispronouncing that — my apologies if I am — at Standing Rock to help decolonize medicine and food. She is a co-founder of the Deep Medicine Circle, an organization committed to healing the wounds of colonialism through food, medicine, story, and learning.

We’re also here with Dr. Raj Patel (PhD), a research professor at the University of Texas at Austin’s Lyndon B. Johnson School of Public Affairs, a professor in the university’s department of nutrition, and a research associate at Rhodes University in South Africa.

He’s the author of Stuffed and Starved and The New York Times‘ best-selling, The Value of Nothing, and the co-author of A History of the World in Seven Cheap Things. And he serves on the International Panel of Experts on sustainable food systems and has advised governments worldwide on the causes and solutions to the crises of sustainability.

Rupa, Raj, thanks so much for being here with us today.

Dr. Raj Patel: Thanks so much for inviting us.

Dr. Rupa Marya: Thank you, Ocean.

Inflammation, Broadly Defined

Ocean Robbins: Well, let’s jump right in here. You’re looking at inflammation broadly, including the human body and the culture, the economy, the world around us. What is inflammation, and why should we care?

Dr. Raj Patel: Well, so inflammation is the way that your body ordinarily heals itself. So in the book, we’ve got this example of a paper cut. When you get a paper cut, you’ll bleed; you’ll see redness; your body will mobilize itself to meet and live with the invaders that may have entered your body through this cut. And this process of inflammation is a way of helping your body return back to normal. That’s a sort of short version of what happens in an acute case of inflammation.

The problem with inflammation that we talk about in the book is that when your body mobilizes its resources when it’s feeling either threatened or is actually under threat or perceives that it may be under threat, that process when the threat never goes away, sends your body into a process, not of healing, but of destruction.

One could say, “All right, well, inflammation, we understand stress, and that’s all very bad and we should have less stress.” But there’s a bigger story here about how the stress that’s around us is part of a story that implicates not just our bodies, but the planet itself. Rupa sees the consequences of this in her medical practice. I wonder, Rupa, if you could tell us a little bit more about the actual sort of biological and social intersections that you see at the hospital?

Confronting Uncomfortable Truths

Dr. Rupa Marya: Yeah, so the inflammatory response is evolutionarily conserved in mammals and animals, also in other life forms. And it is a response to damage or the threat of damage. And it is the way the body or the organism restores its optimal working conditions.

I want to say that as we talk about this… In medicine sometimes, we have to make people a little uncomfortable to be able to offer some healing to offer a way of… You have to lance the wound to get the pus out in order so that a wound can heal and the inflammation can stop.

This book is an opportunity to make people who might not be comfortable with understanding the roots of colonialism, how colonial expansion has destroyed the ecosystems around the world, and the mind view that came with it has set up our structures in our society so that food is not equitably resourced in our lives — that some people have access to lots of healthy food and other people have no access to nutritional food.

So, this discomfort of maybe having to really understand science and why we really laid out the science of inflammation in the book as best as we could in ways that we hope that an average person who’s not used to thinking about these ideas could actually read it, maybe a couple of times if needed, and really understand it and really grasp what’s happening in the body and on the planet — in the Earth’s body. So that discomfort, I just say, is the way through. It’s not for the purpose of just being uncomfortable or just polarizing or just inflaming the dialogue, but it’s to offer people a way of understanding what they’re seeing around them.

The Need For Connection and Community Healing

Dr. Rupa Marya: For me, this was most strikingly seen when I had a patient who was from Muscle Shoals, Alabama — a woman who grew up in a community where she was forced to drink the well water of a polluted watershed: the Tennessee River Valley Watershed.

When she was — in UCSF, where I work as a hospital medicine doctor in the ICU — sick for months, and her son shows up with white supremacist tattoos around his eyes and sits there, and we have a conversation about where they lived, and what their lives are like, and what they’re exposed to, he comes out of the room just crying and motioning to hug me. And I hold him, and he’s sobbing and saying, “No one has ever asked what our lives are like; no one has really seen what’s happening in our communities and how people are dying.”

That to me was like, okay, how do we write this story in a way which will connect all of us who’ve been orphaned from the Earth and all of us who’ve been divided from each other so that we might all have the opportunity to be healthy and pursue lives with dignity? So, that’s how we translated the stories and the learnings from the bedside of patients with the work that Raj and I both do in the communities we serve and work with.

Ocean Robbins: Thank you. I’m moved by your metaphor because I’m thinking if I had cancer, I’d want to know about it; I wouldn’t want to be told a nice story. Finding out about it might make my day a lot less pleasant – I might feel really sad — but we go to doctors for truth, not for nice stories that make us feel good. We actually count on them to tell us the truth, right? So in that sense, I think we want to go to people like yourselves to tell us the truth about the systems that we inhabit.

Embracing Biodiversity

Dr. Rupa Marya: Yeah, I just want to temper that a little bit because the word truth can sometimes scare me and come off as feeling a little religious in some way. So I would say we go to doctors for the best understanding of what’s happening. A synthesis and understanding of the data that’s in front of us. And what is your best understanding of what’s happening.

And of course, as with anything, there will be different people who have different interpretations of the data, and that’s why it is useful to get peer review and multiple ideas and thoughts. That’s what’s been so beautiful about working on this book is how many peers we brought in with us and how much we synthesize different stories.

But yes, it is important that we’re going to understand the patterns that we’re seeing in front of us and understand it with a depth that can actually advance actions that can help shift the course that we’re on right now — because the course we’re on right now is not being shifted fast enough.

Ocean Robbins: Yeah, absolutely.

Dr. Rupa Marya: Sorry to temper that.

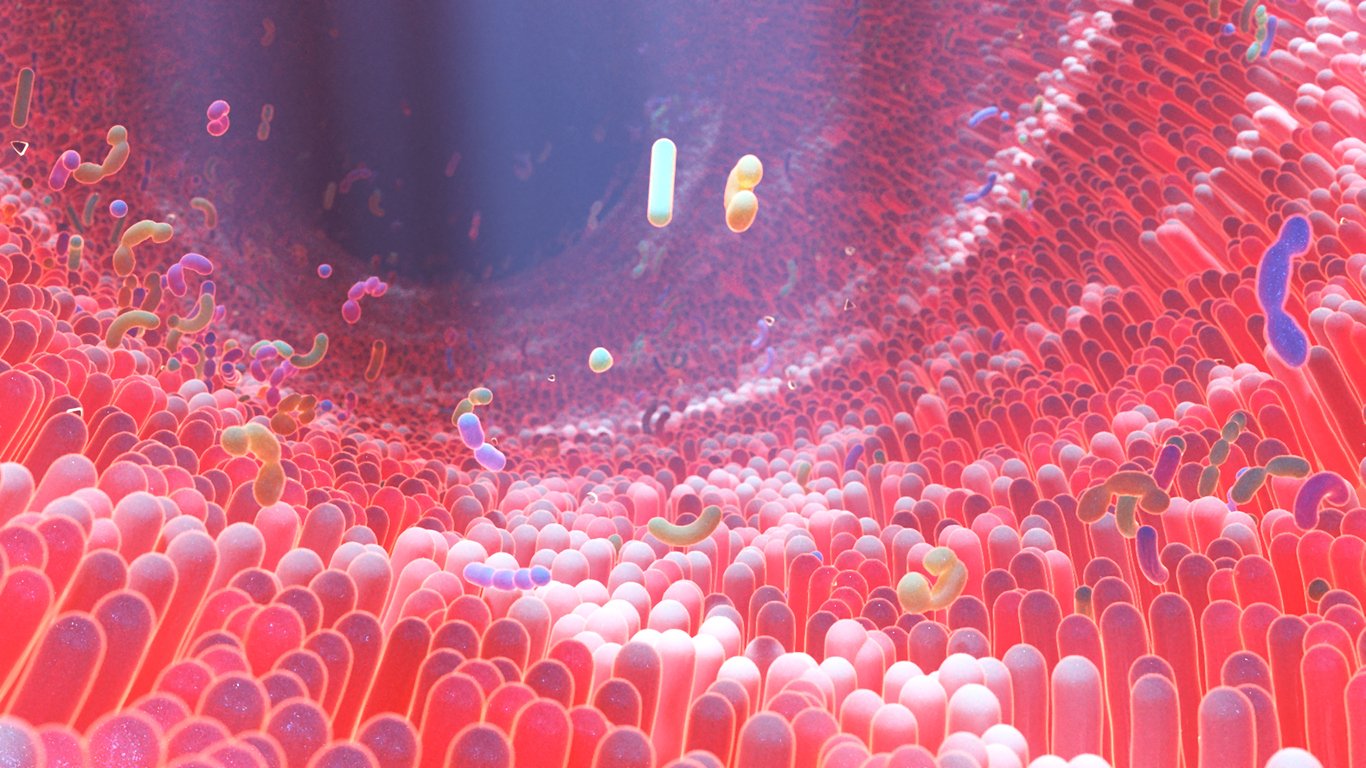

Ocean Robbins: No, I appreciate the nuance. There is no one truth with a capital T. There are facts and realities, but there are also so many different perspectives. And we need a biodiversity of approaches, I think, to create true healing in this world. The sort of notion that there is one right way to live, one right way to think, and everything else should be shut down is part of the sickness, I think, that you’re helping to diagnose here so that we can hopefully create some healing systemically. We don’t just need one probiotic, we need a huge diversity of probiotics for a healthy gut, right? Similarly, there’s no one solution to every problem, but there is a deeper understanding of wisdom that can help us heal, I think.

The Microbiome

Dr. Raj Patel: Yeah. I’m just going to run with that probiotic idea. Because it’s true that we live in a world — and particularly in cities in the global north here — we live in a place where our gut microbiome has been seriously diluted. We may not have a window into our internal microbiome to see quite how diverse it is, but, I remember when I was a kid, we used to cycle around and used to get flies on our teeth, and the windshield would be completely smothered with the life that we were driving through. These days, that doesn’t happen. And the sort of extermination of life that we can see visibly outside is also happening inside us.

And the way to fix that is not through a pill. Because even if you try and rewild your microbiome, the only way that things inside you stay alive is through a relationship with the world outside. And you can’t just re-populate your internal microbiome and think, I’m all right, Jack. That’s not how life within us and external to us works. If the world around us is sick, then there’s no amount of biodiversity within us that will heal that world outside us and will sustain the life within us.

So, I do think, just again, to jump on that idea of the microbiome… I know a lot of people who are very interested in transforming the way that we eat, are very excited about feeding our microbiome, and that’s the right impulse. But, what we’re trying to do in this book is take that impulse outside. It’s like, oh yeah, I’ve got to look after this. My microbiome is not just me, it’s a million different things. But, if that world of chaos stops at the boundary of your skin, then you’re not taking full care of the world as it’s needed in order to be able to rewild ourselves back into a teeming and diverse world.

If the world around us is sick, then there’s no amount of biodiversity within us that will heal that world outside us and will sustain the life within us.

Raj Patel, PhD

Dr. Rupa Marya: Yes. And that’s beautifully said, Raj, because then the microbiome in the gut becomes a living reflection of a whole system of care and a whole system of relationships with the world around you. And so, that’s how you know, and that’s one of the things we talk about in the book, is that we will know we’re making progress when we start to see our bodies become less inflamed.

Complexities & Inequities in Health

Ocean Robbins: Yeah. So, you talked about your patient who came to you having drunk or actually eaten fish from a river that was polluted and now was suffering from serious inflammation that eventually, I think, took her life. And it strikes me that one of the dangers of the natural health movement is that there’s a half-truth in that we are responsible for our own health outcomes, and we need to take responsibility for them — what we eat and how we live has a massive impact on our well-being.

But the other half of it is that we’re impacted by our environment, by our ecosystem, by forces outside of us as well. And yes, personal habits and personal choices will profoundly influence how we respond to pathogens, how resourceful and resilient our organism is in the face of assaults or challenges that it may face, but it’s not the whole story.

A lot of things were shaped in the womb and in early childhood. And now here we are; we don’t get to rewrite history. So, we do the best we can, of course, with what we’ve got, right? And that’s back to the serenity prayer. Give me the serenity to accept the things I can’t change, the courage to change the things I can, and the wisdom to know the difference, right?

At the same time, I, like you, want to think systemically at how we create the conditions where less kids are inheriting wounded biology and pathogens that they then have to suffer through and figure out how to detoxify or not throughout their entire lives. And a lot of that comes back to the collective well-being and the environment on the health of the ecosystems we inhabit. Are we living in toxins? Are we breathing polluted air? Are we around diverse, healthy soil? Do we get to bring some of those microbes into our bodies? Or do we live in hyper sterile, or worse yet, hyper polluted ecosystems?

And the answers to these questions have a profound race and class dynamic to them. So, statistically, your likelihood of living in a healthy environment, in a safe environment, is different depending on your financial context and your ethnic background, and your nationality, right? And this is one of the things I think you guys are highlighting so powerfully in your work is that if we really want to heal ourselves, we need to start to heal the world. And we need to look at the fact that that doesn’t show up equally for everybody.

Dr. Rupa Marya: Absolutely.

Stress & Inflammation in the Working Class

Dr. Raj Patel: You talked about how this is a problem for everyone. It’s certainly the case. And that’s something that is true also across races, for example, when it comes to conversations about class. Because one of the things that really surprised me in working with a group on this book is just how the story of inflammation works into our body.

So, for instance, one of the things about being working class in the United States is that you are disproportionately exposed to things like payday loans. For folks who are lucky enough not to know what that is, it’s when you need $200 to make it through the end of the month, but then you have to pay $500 back within a couple of months.

Now, those kinds of loans are so bad in terms of stress of repayment and the kinds of despair that people get driven into afterward, that if we were to treat payday loans as illegal — if we were to just proscribe them and say, look, you can’t do payday loans anymore — then the suicide rate in the United States would drop by 2%. And the fatal drug overdose poisoning rate would drop by 8.9%.

Ocean Robbins: Wow.

Dr. Raj Patel: Here’s a treatment. Here’s a medicine to help people who are on the frontlines. Doesn’t matter what race you are. If you are struggling with making ends meet… Payday loans are an incredibly bad idea, and we need to take them off the table. But, understanding that actually the boundaries of medicine go beyond what the FDA approves or disapproves of and goes all the way from things like toxic financial policy, all the way to the food system, and meets in the middle. I think that part of the story that we’re telling here in Inflamed is a story about how the world of medicine, the world of food, the world of society are all conjoined in ways that we’ve been miseducated in trying to draw divisions between them.

The Divisions Between Medicine and Food

Ocean Robbins: Yes. So, we’re Food Revolution Network. We focus on food a lot. And I’ve often reflected that most doctors today act like food didn’t matter. And quite frankly, the food industry today acts like health didn’t matter, in many cases. Yet, the truth is that food is the foundation of health. And it should be the first line of defense against disease. And yet, we have this separation.

Why are there these divisions between medicine and food? And is it just purely that doctors are trained to not think that way and the food industry is just trained to look out for profits, or are there deeper sources here around this division?

Dr. Rupa Marya: Well, this is what we dive into in the book, which is really the Enlightenment-era errors that have persisted in colonial capitalist society and have structured everything from the food system to our education system.

So, all the axises of care have literally been fractured from each other. And part of this has to do with how this land was colonized — that Europeans, when they came here, separated white male property people from everybody else. And those folks were civilized and all the rest of us were uncivilized. So, once you’re uncivilized, you’re able to be dominated and extracted from. And so, that mentality of extraction, which is pervasive in the industrialized food system, and even the softer, greener, fuzzier, conscious capitalist food system, these things are extractive. At their core, they’re extractive. They’re not based in systems of relationships. And so, that’s why doctors don’t know how to think about food, or even think about that your mind and body are actually one entity, that the separation of self and other is another fiction that we have to overcome.

This is something that we really dive into in the book, is what we call the colonial cosmology, and how that underpins the architecture of all of our institutions in this society; and how that way of thinking is actually a part of what’s making us sick. Because it’s doing precisely what you’re saying, Ocean: it’s doctors not understanding why it’s important to have nutrition, nutritious food, and where that plays a role.

Nutrition and COVID-19

Dr. Rupa Marya: What we’re seeing in COVID… I just took care of a young, 37-year-old unvaccinated woman with severe COVID just yesterday in the hospital. And her nutrition markers were terrible. This is a young woman who’s a mother of three children, who has very poor nutritional markers. Because what’s available to the average person, the average working-class person, is not whole food; it’s not nutritious food. And, it’s food that’s been laced with pesticides. You’ll have traces of these pesticides and dietary chemicals, which we also know impact the gut microbiome.

And so, even if you try your best to take the right supplements and take the right probiotics, it won’t work in the face of the constant onslaught. And so that is what we’re talking about. How do we restructure our society and world so that onslaught stops, so that everyone can have the opportunity to be healthy?

Ocean Robbins: Yeah. There was a recent study, six countries, thousands of healthcare workers, and they were analyzing their diet and their COVID context. And they found that people who ate a whole foods, plant-based diet had 73% less risk of hospitalization than their peers who ate a more standard industrialized diet. Seventy-three percent reduction in risk of hospitalization. These healthcare workers were all exposed to COVID-19 in similar amounts.

And then, we have other data from the CDC showing that 95% of COVID-19 deaths in the United States have been linked to underlying comorbidities, which are, all of them, profoundly diet- and lifestyle-impacted. And —

Systemic Health Injustices

Dr. Rupa Marya: Yes. I want to say though, I just want to offer some shape to that. Because when we’re talking about obesity, cardiovascular disease, diabetes, and these are the things I think you’re referring to — those things are diet-related, and they’re also related to the history of genocide of Indigenous people. They’re also related to how much your neighborhood is policed, and how terrorized you are by police. It’s related to trauma. It’s related to having your language ripped away from you. So it’s way more whole than just are you eating the right things, and are you living the right way?

Ocean Robbins: Right.

Dr. Rupa Marya: Because, I just want to say that because for some people, that opportunity, even if they ate the best diet that they could and were exercising, they’ll never have that opportunity to counter those things.

Ocean Robbins: And just to add a data point to that… As we know, life expectancy in the United States dropped in the first year of the pandemic by a year for the white population; it dropped for three years for the Black population in the United States. So we’re seeing here that death rates were much higher amongst Black people, and also Indigenous and Latino communities than the white population. And that links to what you’re saying, the chronic inflammation that’s caused by so many other factors. Of course, there’s diet and lifestyle, but there’s also trauma and the impact of that trauma. And so, I appreciate you’re raising that larger systemic piece.

And again, it’s like we do all that we can personally, none of us wants to be a victim. At the same time, let’s look at the systemic dynamics that do victimize some people, quite frankly, in serious ways. Raj, did you want to add to this too?

Food Industry Follies

Dr. Raj Patel: Yes. The way that the food industry behaves is also worth flagging here. A report came out, a leaked report from within Nestle, pointing out the vast majority of the food that it produces doesn’t meet a basic definition of being healthy. Again, there’s a rhythm to the patterns of exposure to unhealthy food when the food industry systematically targets low-income communities and communities of people of color with the least healthy food.

So, it’s not an accident that the food industry is targeting certain kinds of neighborhoods, certain kinds of communities for advertising, for example. And, the lack of accident there has everything to do with, again, the damaging consequences of consuming the industrial food system, which is, again, premised as Rupa was saying, on a racist and exploitative and genocidal history.

Just to give some numbers here. In 2019, Americans spent $1.1 trillion on food. Just a very limited calculation of the damage caused by the food system through those purchases set the number at around $2.1 trillion. So $1.1 trillion spent, $2.1 trillion of damage, and the majority of that was precisely in the generation of these comorbidities, again, which are patterned not in a random way, but in a very targeted way that follows the contours of power in society.

And so, now we’re all familiar with comorbidities, but we all ought to become a bit more familiar with the mechanisms through which they are projected into our bodies by these large corporations. And I don’t care how conscious they pretend to be. When you’ve got Nestle saying, “We’re trying to take some sugar out of our food,” that’s — as well they know — basically pissing about around the edges, when essentially their business model depends on the production of externalities that will generate, and as they know full well, the death, in particular, of communities of people of color and low-income communities.

Identifying Solutions

Ocean Robbins: Yeah. Okay. So, some of our viewers right now might be saying, “This is really heavy stuff.” When you’re saying the dominant systems that we depend on to feed families are morally bankrupt and are causing this harm, and then you’re saying that the even greener versions are warmer and fuzzier, but they’re still fundamentally connected to the same extractive systems that are fueling a lot of the crises, what can we do about it? Personally and collectively, what’s the prescription here?

The Need for Deep Medicine

Dr. Rupa Marya: Well, the prescription is deep medicine, Ocean. And I’m happy to tell you about a project we’re doing as a model that could be replicated all over this country, all over the place.

So, we started an organization called The Deep Medicine Circle. We are a collective of non-Indigenous and Indigenous people working together to advance systems of farming that prioritize Indigenous principles of earth care and people care. We are working on re-matriating, returning 38 acres of land to the Ramaytush Ohlone here, the original people of the San Francisco Peninsula. And we’re working under their leadership to create food to give away to people oppressed by hunger in the city.

So we’re in the peri-urban areas; we’re like 40 minutes south of San Francisco. All the food that we’ll be growing will be, I call it morganic because it’s not just organic. But we’re working on improving soil biodiversity. We are working on area median income wages for our farmers so that they’re employed and healthy. And they’re also being valued for the work of stewardship that they’re doing for the soil and for the food.

And then that food is just liberated from the market economy. It’s going to people whose gut microbiome needs it the most. And then we see how that shifts our narratives of health and wellness. So, we can flip the food system on its head and prioritize care, or we could keep it as it is and try to eke out a profit as we try to do these things. The profit motive of the food industry, as with the healthcare industry — as we’re watching in the United States — is always going to make it less effective and efficient at conveying care.

And what we need right now is care. We need care and repair of the damage that’s been done to our soils, to our water, and to our Indigenous people. The IPCC report on climate change did say that Indigenous people and their systems of knowledge are critical to addressing climate change throughout the world. So it’s a great time to give land back, give all the land back, and start working under Indigenous people’s understandings of how to be in right relationship in this land.

And I know that might sound like, “Whoa, how do you do that?” Well, you do it in little bits, and you do it in big bits, and it’s happening right now. There are many projects all over Turtle Island, all over this land, and all over the world, frankly, where people are starting and have been building these movements of peasant farmers and small to medium farmers, who’ve always fed, always created the most food that people eat on Planet Earth. So that’s reassuring, and it’s exciting.

What do you think, Raj?

A Duty of Liberation

Dr. Raj Patel: I think people should give to the Deep Medicine Circle of which I am a treasurer and, therefore, I need to declare an interest. But I do think that there are… Part of the debilitating moment here is, the reason this feels so big and unwieldy is because we’ve been so conditioned into our powerlessness, thinking that the only way that we can change the world is by shopping and really spending quite a lot of money on the right probiotic. And if that’s what we think, really the only way that we can save the world is through our shopping habits, we let go of perhaps the most important levers of change that we have, which is our relationships with one another and the rest of the web of life.

And, to reconnect to that is, it can feel like some sort of woke duty. And for those folk who are entering this conversation and thinking, “Look, I get it that there are things wrong with the world, but there’s so much to do.” The one way to frame it is to feel it as a duty of just suffering and of abnegation. But the other way, and I think possibly the better, in fact, definitely, the better and the more correct way of understanding this is a duty of liberation.

And the reason it feels so difficult is that’s the sort of voice inside your head that makes you feel powerless and overwhelmed by everything as opposed to ready for transformation and change. And the more we’re in the readiness for transformation and change space, the happier we’re going to be because ultimately changes are coming. We’ve seen what climate change is doing, and it’s only getting worse as well we know. So why not lean into the need for change and understand it as a liberation rather than as a kind of retreat into a smaller, shallow life when in fact the opposite is the case.

Ocean Robbins: Thank you.

Dr. Rupa Marya: And that’s really the space of the imagination. I think what we’re talking about here is it’s so sad that arts funding has been cut so much in school because so much of this work is the act of imagining new ways of being together that we’ve never actually had an opportunity to ever experience on a large social scale. What does that look like? What does it feel like to escape from the social structures that have been imposed upon us that we’ve internalized? And we’ve been unwitting recreators of that violence. It’s an opportunity to open up that consciousness and step through another door. And through that, the richness of relationships is so exciting and actually invigorates new possibilities, new economies, new ways of carrying out our daily living, which is exciting.

Opening The Door of Opportunity

Ocean Robbins: Yeah. Thank you for that.

I think that many of us feel, deep in our bones, that the world we’ve been fed isn’t satisfying to us anymore. So many people feel this longing for another way of living, feel a sense of isolation and loneliness, feel a sense of disconnection, and feel as if we’re stuck in a rat race, so to speak — trying to survive and win a race that even if we win it, are we really going to be happy? Even people who succeed at the top of the heap often feel deeply lonely and bereft inside like, “I’ve got everything I want, but for what?” And then so many other people feel like if they could just get a little higher on the ladder, then they’d be okay. Meanwhile, they’re struggling just to survive. And so many of us are wondering, “Is there something more? Is there something deeper?”

And the notion that the breakdown of established systems and institutions and even ecosystems might open the opportunity for some kind of a breakthrough to another way of living in harmony with our own rhythms, in harmony with the Earth as a community, rather than just as a way to try to get to the top, is liberating I think. To something… It’s humanizing in the deepest sense.

And so, now I really want to thank both of you for shining such a brilliant light on what’s possible, for sharing, in very sobering terms, what we’re up against and the costs of the status quo. Because we’ve got to face that, I think, to really have the impetus to change it. As long as it’s sort of okay, we’d rather take what’s tolerable to the unknown sometimes. But when we realize how broken things are, and, in fact, maybe they’re not broken, maybe they’re designed for something that isn’t what we want to be designed for, then we start to realize, wow, what else is possible? And you’re helping shine that light and the notion that we could be healthier; we could be happier, and we could contribute to a healthier and happier world is a beautiful one. So, I thank you both.

Any closing words you’d like to share from our time today?

Choosing Care Before Consumption

Dr. Rupa Marya: One of the scholars we talked to, Sam Grey, who is just so amazing, she brought up this concept of being orphaned — that we’ve all been orphaned from our mother. I remember she said that, and it just really hit my heart. Like, “Oh my God. Why am I born here in Ohlone territory? Why is Raj? Where have we been dragged about from our families, these diasporas, these refugees of colonial terror?” We’ve all been separated from our homelands. The people who’ve been colonized here. We’ve all been cut off.

So what we must do is heal and repair those connections wherever we are. And that really is contending with these systems of domination that put us in places of really illegitimate privilege, that we must challenge and invite ourselves to overturn. And what wealth of relationship comes on the other end of that. It’s tremendously exciting.

I can tell you, I’m a songwriter. And this work I’m doing right now with Deep Medicine Circle is the opera of my life — the most beautiful symphony I’ve ever heard. And so, I invite everyone to find that work in their own orphanhood. It’s time for us all to come home.

And so, I’m excited. It’s healing work. It’s deep work. It’s confronting trauma. It’s hard work. And if we all do it together, it can be a beautiful journey.

Ocean Robbins: Yeah. Thank you. Raj?

Dr. Raj Patel: I couldn’t say it better than that. So I… Yeah. I think this work of care for one another and recognizing how big the community is that’s caring for us and for whom we can care is just a revelation. And it’s so much better to care than consume.

And I think ensuring that we all care so that we can all consume fairly, I think, is definitely the message we’ve got in Inflamed. And I’m just very grateful to have written it with Rupa. And Ocean, that you’ve invited us here and that you’ve spent so much time with the book and with its messages. It’s a privilege.

Ocean Robbins: Thank you both. We’ve been talking with Dr. Rupa Marya and Dr. Raj Patel, authors of Inflamed: Deep Medicine and the Anatomy of Injustice. Fantastic book; critically important message. Thank you again.

Dr. Rupa Marya: Thank you, Ocean.