by Cara Jepsen: It is almost 6 A.M. and for the second year in a row you find yourself on the top floor of New York City’s historic Puck Building, waiting for Guruji.  A familiar lack of sleep lends a surreal aspect to the large, pleasant ballroom, which is bounded by windows on three sides. It is still dark outside; the moon is waning and the sun is just about to rise. The workshop starts on Labor Day–the last chance for Manhattanites to hit their Hamptons summer rentals–and while the room is crowded, it’s not exactly a sold-out show. Already there’s a smattering of people holding bouquets of flowers, waiting for their man.

A familiar lack of sleep lends a surreal aspect to the large, pleasant ballroom, which is bounded by windows on three sides. It is still dark outside; the moon is waning and the sun is just about to rise. The workshop starts on Labor Day–the last chance for Manhattanites to hit their Hamptons summer rentals–and while the room is crowded, it’s not exactly a sold-out show. Already there’s a smattering of people holding bouquets of flowers, waiting for their man.

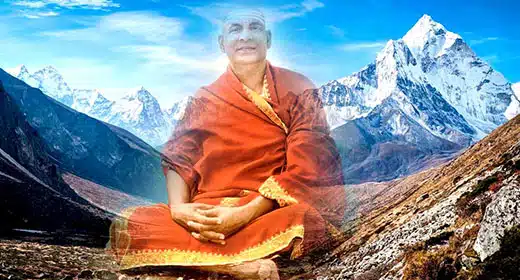

In September, Sri K. Pattabhi Jois began the month-long New York leg of his Next Last World Tour (he’s had several “last” tours), which included stops in Helsinki and London. This time around the 86-year-old founder of the Ashtanga Yoga Research Institute (AYRI) in Mysore, India, made only one U.S. appearance, in New York City. And instead of being joined by his son, Manju, this time his daughter, Saraswathi Rangaswamy, was with him. As usual, he was also joined by his 30-year old grandson Sharathchandra Rangaswamy, the assistant director of the AYRI and the most advanced ashtanga vinyasa yoga practitioner in the world. In addition to the morning workshop Sharath taught Mysore-style (self-practice) classes in the afternoons for a small group at Eddie Stern’s Patanjali Yoga Shala.

In September, Sri K. Pattabhi Jois began the month-long New York leg of his Next Last World Tour (he’s had several “last” tours), which included stops in Helsinki and London. This time around the 86-year-old founder of the Ashtanga Yoga Research Institute (AYRI) in Mysore, India, made only one U.S. appearance, in New York City. And instead of being joined by his son, Manju, this time his daughter, Saraswathi Rangaswamy, was with him. As usual, he was also joined by his 30-year old grandson Sharathchandra Rangaswamy, the assistant director of the AYRI and the most advanced ashtanga vinyasa yoga practitioner in the world. In addition to the morning workshop Sharath taught Mysore-style (self-practice) classes in the afternoons for a small group at Eddie Stern’s Patanjali Yoga Shala.

The sun begins to rise behind Guruji as he leads nearly 200 people in chanting the traditional invocation. On this first day you are “hiding” in the third row, nursing a sore left shoulder, and are pleased when you are led through only three of each sun salutation. Nonetheless, Guruji, who calls out the poses in loud, clear Sanskrit from the front row, finds you and treats you to his famous baddha konasana (bound angle) adjustment–standing on your thighs as he presses your chest into the floor. Sharath and Saraswathi give adjustments and encouragement in the middle and back of the room. The three urdhva dhanurasanas (upward facing bows) Guruji leads the class through, without a rest in between, are mercifully short.

From 1927 to 1952, Guruji studied yoga under the modern yoga master Tirumalai Krishnamacharya at the Mysore Palace. (Krishnamacharya’s own lineage can be traced back to the tenth century C.E. Vishnu devotee Nathamuni.) Both were Sanskrit scholars (Guruji attended the Sanskrit College of Mysore from 1930 to 1956, and headed the yoga department there from 1937 to 1973). While doing library research in Calcutta, Krishnamacharya discovered ancient texts written on palm leaves that described what are now known as the ashtanga yoga series. They emphasized vinyasas (movement linked with breath), dristi (gaze) and ujjayi breath. The pair worked on reconstructing the texts, and Krishnamacharya asked Guruji to make it his life’s work. Guruji opened the AYRI in 1942.

On the second day, class meets on the first floor of the Puck Building–which requires walking over broken glass and garbage to get to the back door. It’s a small price to pay to see the man who made it possible for you to learn this life-changing practice. It’s more crowded today, but you find a spot in the second row. Poses are held longer, and you receive several adjustments–perhaps Guruji remembers you from last year. Or maybe your renditions of paschimottanasana, ardha baddha padma paschimottanasana and salamba sarvangasana (seated forward bend, half-bound lotus seated forward bend, and shoulderstand) are crying out for help. Like last year, he admonishes people now and then with a “bad lady!” or “bad man!” if they move ahead before they’re told. In urdhva dhanurasana your shoulders are OK, but your arms feel weak, weak, weak. In headstand you watch Guruji approach someone who’s avoiding the pose. He says “Why? Up!” and up they go (for awhile anyway).

For the first two weeks of the workshop, the 8 A.M. class does half of the primary series–through navasana (boat pose). For the final two weeks, the 8am class is for the intermediate series, which involves a lot of backbends and twists and is meant to cleanse the nervous system. A demonstration and discussion with Guruji and Sharath that was scheduled to take place at Jivamukti Yoga Center was canceled “due to miscommunication,” but in the last week of the workshop Guruji and others gave an evening talk about yoga at the Puck Building.

You oversleep one day and are told it’s “just fine” if you practice with the 8 A.M. group. You find you’re not as stiff and weak this late in the day. You and your equally tall and stiff neighbor are the recipient of one of Guruji’s other famous adjustments–the double utthita hasta padangusthasana (standing leg raises)– in which he helps you both in the difficult balance pose, at the same time. (He does this again a few days later, telling you to press your foot into his hand; then he laughs and says, “After three weeks, you will be strong.” But you only have two weeks, you want to tell him). Later, you fumble in janu sirsasana C (head-to-knee pose)–an asana with which you have a hate-hate relationship, despite getting plenty of help in it at last year’s workshop. Guruji says, “You go!” and you do (sort of). Later, in headstand, you are able to hold urdhva dandasana for the full count–something you’ve been trying to do since you saw Guruji last year. You should sleep in more often.

Some students attended the workshop for just one day, while others were there for the entire month. Sharon Gannon and David LIfe, founders of the Jivamukti Yoga Center, were present, as were Willem Dafoe and Gwynneth Paltrow (one day even Rodney Yee showed up). As in Mysore, Guruji taught every day but Saturdays and moon days. (For the record, we did just two versions of paschimottanasana, five navasanas, and only one variation of baddha konasana).

You’ve been walking through instead of jumping through vinyasas because of your sore shoulder. You are about to shuffle forward as usual when you notice two calloused feet in front of your hands–Guruji’s. You jump forward instead, and continue to do so for the rest of the workshop. Somehow, your shoulder has healed itself, and for the umpteenth time you realize there is something truly profound about Guruji’s axiom–“Practice and all is coming.”

Like last year, some poses were held longer than others. Urdhva mukha paschimottanasana (balancing forward bend) seemed to go on for an eternity as the three generations of teachers pressed chins into shins. The final pose before savasana, utpluthih (the uprooting, similar to tolasana) became a test of will as Guruji took his time counting to ten. He’d find someone who’d given up, smile and say, “Up! Up!” A fellow student said we held the pose for an average of 45 breaths. Nonetheless, another Chicagoan said he found the hour and a half went by surprisingly fast.

For a few days during the second week, the workshop takes place at a gym at Chelsea Piers, where everyone practices together at 6. You spread your mats on three basketball courts that are surrounded by a track, a boxing ring and a weight training area. On the second day at the Piers, just before savasana, you and nearly 300 other yoginis sing “Happy Birthday” to Saraswathi, who’s 60, as Eddie and his teachers walk in with a cake. Later, when you kiss Guruji’s feet, you tell him your name. He says, “You come to Mysore?” and you tell him yes, in January. “Good, good,” he says, and pats your cheek.

That was on September 11. Before the attack.

You are walking home from class with a friend when you notice a huge cloud of black smoke in the sky. “That doesn’t seem right,” you say. You turn a corner and your friend’s mother grabs you and says, ‘”You have to see this. The World Trade Center is on fire.” You walk to where a crowd is gathered near Hudson Street, looking towards the WTC. At first it seems like a freak accident–somehow a plane went out of control. In your post-yoga fog, you vaguely wonder how the fire trucks will get their hoses to reach that high. Then the other tower is on fire, and everyone knows it is not an accident. Some people start crying, and everyone is on their cell phones; a blonde man says a 767 hit the building. The next two days pass in a blur of horrific images, calls to family and friends, panic attacks and impotent attempts to help.

The outgoing message on the Patanjali Yoga Shala answering machine said that yoga was canceled on Wednesday, although a handful of people did show up at Chelsea Piers (later used as a morgue) and practiced anyway. On Thursday the Puck Building was still closed, so class was held at Eddie Stern’s pleasant, peach-colored studio in SoHo, which holds 40 people (students were divided into three groups based on their last names). The studio is south of Houston (the “Ho” in SoHo), a “frozen area” that was off-limits to non-residents (those who could not get through got refunds or made up the class later).

The streets are empty as you walk to Eddie’s. You approach the officer at the barricade, show him your I.D. and explain that you’re going to a yoga workshop. It works, and you and a couple of people behind you, also with mats, are let through. “We’re in!” one of them says. She wears a dust mask and walks in the streets “because of the rats.” Indeed, garbage hasn’t been picked up in awhile and is piling up.

About 40 people showed up for the first session on Thursday. One of Eddie’s teacher was on the phone, telling someone to try to get through at another checkpoint. No one talked before class, which was unusual, and the mood was somber.

During class Guruji doesn’t make a single “bad lady” joke, and none of the poses are held very long. You are distracted, weak, and stiff and have no balance. There are a lot of sirens. But at least it’s warm, and you break your first sweat in several days. Halfway through practice you realize that whatever happens, the primary series, and its effect on you, will not change. Before savasana, Eddie says to call after 11:30 to find out if/when you will practice on Friday. On the way out you hear someone say, “If it were just the bad smell, that would be one thing…”

The workshop resumed at the Puck Building on Friday, and the missed class on Wednesday was rescheduled for Saturday, when everyone practiced together at 6 A.M.

On Friday you are nauseous and migrainy and sleep through class, dreaming about asbestos and disaster. Saturday, the day you are to fly home, there only about 80 people in class. You receive a lot of adjustments. Guruji seems to be in better spirits, and savasana seems to go on forever–or maybe it just seems that way. While kissing Guruji’s feet, you experience a million emotions, the most dominant of which is loss. Will you see Guruji in January? What will the world be like then?

Later you are walking through the lobby with a group of people, deep in a post-practice fog, when a woman in front of you screams, “OH MY GOD!” Everyone jumps back three feet and ducks their heads. Turns out the woman recognized someone she hadn’t seen since Tuesday.