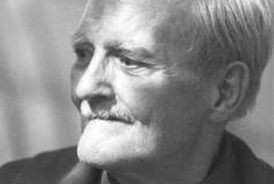

Since Milton Erickson was born and raised in pioneering and rural farming country, there were few medical or educational facilities.  “Schooling” was simple and basic, which may be whey not one (apparently) noticed that the young Milton was experiencing the world in his own unique manner.

“Schooling” was simple and basic, which may be whey not one (apparently) noticed that the young Milton was experiencing the world in his own unique manner.

Many of Erickson’s earliest memories dealt with the way his perceptions differed from others’ due to several constitutional problems: for one, he was color-blind*; for another, he was tone deaf and could neither recognize nor execute the typical rhythms of music and song; and still another, he was dyslexic – problem which was indeed perplexing to his childhood mind and which he only recognized and understood by hindsight many, many years later. *(There is common myth that Erickson could see only the color purple as a result of a rare type of color blindness. According to Betty Erickson, this was not true. Milton had a common type of red-green blindness called “dichromatopsia.” Purple became his favorite color, but he probably perceived it as a kind of darkened blue. Betty suggest that he chose purple early on because at that time it was rarely used for garments – and Milton thoroughly enjoyed being different. Eventually purple became his own personal trademark.)

The misunderstandings, inconsistencies and confusions that arose because of these deviations from the common, everyday world view might have inhibited another person’s mental functioning. In the young Milton, however, these differences apparently had the opposite effect: they stimulated wonderment and curiosity. more importantly, they led to secession of unusual experiences which formed he foundation for a lifetime of research into the relativity of human perception and the problems that arose because of it; and into therapeutic approaches dealing with those problems. (p. 5)

One day, when he was in his early seventies, Erickson recounted and discussed some of these experience with me and fellows: As a six-year-old child Erickson was apparently handicapped with dyslexia. Try as she might, his teacher could not convince him that a “3” and an “m” were not the same. One day the teacher wrote a 3 and then an m by guiding his hand with her own. Still Erickson could not recognize the difference. Suddenly he experienced a spontaneous visual hallucination in which he saw the difference in a blinding flash of light. (p.5-6)

Erickson: “Can you imagine how bewildering it is? Then one day, it’s so amazing, there was a sudden burst of atomic light. I saw the m and I saw the 3. The m was standing on its legs and the 3 was on its side with the leges sticking out. The blinding flash of light! It was so bright! It cast into oblivion every other thing. There was a blinding flash of light and in the center of that terrible outburst of light was the 3 and the m.” (p. 6)

Depth of trance: “You want to go into trance; you want to achieve certain results. You don’t know whether it’s a light trance, a deep trance, or a medium trance that you want , and neither do I. I think you and I ought to let your unconscious mind us whatever amount of light trance, whatever amount of medium trance, and whatever about of deep trance that your unconscious naturally feels will be most helpful.” (p. 133)

The Permissive Technique: Now I would like to discuss the matter of producing results.

When you want to ask your patient to do something. I think it is a very serious error not to ask him first to cooperate with you – unless, of course, you have a specific reason for not doing so. I like to use a permissive technique. In certain cases, however, you may need to use the authoritative technique: “I want you to move your finger.” When a patient rouse from trance in the middle of his operation the anesthesiologist can say very sweetly but very emphatically: “Now, that you have awakened and you notice that everything is fine, you might as well go right back to sleep.” And the anesthesiologist ought to mean that and to say it in a sufficiently authoritative fashion so that the patient responds. But to elicit the cooperation of the patient one ought to be permissive for best results. One really ought to ask the patient to cooperate in achieving a common goal. You should keep in mind the common goal is a goal for the welfare of the patient wherein the patient is cooperating with you to achieve something that primarily is of benefit to him. (p.165-166)

PSYCHOSOMATIC MEDICINE: Hypnosis has long been recognized by people, but its history in terms of scientific recognition has been rather short. That is because hypnosis has been regarded as a matter of mysticism, cultism, superstition. (but hypnosis is really a matter of mental mechanisms,) and why shouldn’t science be interested in the function of those mechanisms: The brain cells do control the body in a great variety of ways – neurologically, physiologically, and psychologically as well.

Hypnosis really got its start in modern medicine in the second decade of this century when people became interested in that peculiar concept called “psychosomatic medicine.” Frances Durbar was very much criticized and ostracized when she first began her studies on psychosomatic medicine, because who on earth was going to believe that business worries or marital worries, or any kind of worries in the head could result in ulcers of the stomach!

Yet, the general public adopted that notion, understanding that worries, be they real or imaginary, could produce a great many physical complaints and physiological alterations. And because that general public go behind the notion of psychosomatic medicine, the physicians who were so dubious about it were literally forced to consider and investigate it. With this recognition of the importance of brain/mind functioning on the rest of the body and the subsequent development of psychosomatic medicine, provision was made at last for the induction of hypnosis as an adjunctive technique in the practice of medicine. (p 181)

PSYCHOLOGICAL FRAMEWORK OF PAIN: To understand pain still further you must realize that it is a neuro-, psycho-, physiological compels characterized by various understandings of tremendous significance to the sufferer. It is precisely for this reason that pain as an experience is amenable to hypnotic treatment. Because pain varies in nature and intensity, it acquires many and varying secondary meanings to the individual in the course of a lifetime, and this in turn, results in widely varying interpretations of it. Thus the patient may regard his pain in temporal terms – experiencing it as transient, recurrent, persistent, acute, chronic; or he may regard it in emotional terms – finding it irritating, troublesome, all-compelling, incapacitating, distressing, depressing, intractable, vitally dangerous; or he may regard it in terms of sensation – experiencing it as dull, heavy, draggy, sharp, cutting, twisting, burning, nagging, stabbing, lancinating, biting, cold, hot, hard, grinding, throbbing, gnawing, and a wealth of other adjectival terms. (p. 221) It is awfully important to have your patient describe his pain in his own words, and to have him describe it fully. (p. 221-222)

TRANCE DEEPENING AS FUNCTION OF PATIENT NEED: Regarding this matter of deepening hypnosis, I have found that often too much effort is put into deepening a hypnotic trance. My feeling is that patients should go no deeper into trance than they need to go. Therefore, I tell my patients the following: “Now, some patients need to go very deeply into hypnosis and some patients can accomplish everything they need to accomplish while they are a very light stage of hypnosis. Neither you nor I know what degree of hypnosis is requisite for you, but I think you are willing to develop that degree of hypnosis that is requisite for you to give your full attention to the therapeutic accomplishments that you need. I think that you are willing to develop that degree of hypnosis that is requisite for you to accomplish the therapeutic achievements that you desire.” (p. 248)

I state it in such a way that patients are free to be in a light, a medium trance, or a deep trance. I have not made an issue out of going deeper; I have not made an issue out of staying in a light trance; I have not made an issue out of staying in a medium trance. I have simply made an issue out of going as deeply as they need to go. Why should patients go any deeper than they need to go? If you are afraid of deep water, why not swim in water that is shallow?; after all, you can swim in water that is thirty feet deep! Why not let your patients have that same freedom? (p. 248-249)