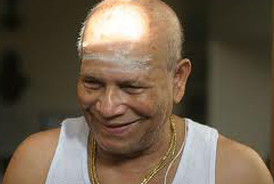

by Alexander Medin: Sri K. Pattabhi Jois has become a renowned name in the world of Yoga, but like his teacher Krishnamacharya, it is primarily his students that have brought attention to his name in reference to where they received their teaching from. Pattabhi Jois, now 92 years old, has been teaching yoga for seventy years, but it is primarily in the last ten years the world came to know about him, since all his Western students started to spread his teaching in various parts of the world.

it is primarily his students that have brought attention to his name in reference to where they received their teaching from. Pattabhi Jois, now 92 years old, has been teaching yoga for seventy years, but it is primarily in the last ten years the world came to know about him, since all his Western students started to spread his teaching in various parts of the world.

Today it is quite normal that more than 200 foreigners queue up at his house every month to learn the particular style of Yoga that he teaches. Whenever he travels the world, he receives the attention of a modern rock star, and hundreds of people willingly sign up for his simple courses wherever he goes. However, Pattabhi Jois’s life story is paved with struggles and demands, suffering and tragedies, but without ever losing faith in Yoga and the method he has been spreading. While teaching Yoga for 37 years at the Sanskrit College in Mysore, he was the lowest paid teacher and had no chance of supporting his family without extra work on the side. However, due to generous support from local people in the area, Pattabhi Jois was able to continue focusing on his teaching of Yoga and could therefore surrender his life to refining the teachings he received from his guru, Tirumalai Krishnamacharya.

Pattabhi Jois was also one of the first students of Krishnamacharya. The two first met in Hassan, Karnataka in 1927 where Krishnamacharya was doing a Yoga demonstration in the Jubilee Hall. Pattabhi Jois became so overwhelmed by what he saw that the following day he approached Krishnamacharya for instruction. Although Krishnamacharya left him to practice on his own a few months later, their teacher-student relationship was to last for nearly thirty years. During this period, Pattabhi Jois had the great fortune of learning asana, pranayama and various aspects of Indian philosophy from T. Krishnamacharya, alias “The Grandfather of Modern Yoga.”

At the age of fifteen, Pattabhi Jois had a keen interest to pursue Yoga and his Sanskrit studies further, so he therefore ran away from home and left his native village to secretly beg for admission at the Maharaja’s Sanskirt College in Mysore. Here he was reunited with Krishnamacharya, and they continued their close relationship until Krishnamacharya eventually departed for Madras in 1953.

Pattabhi Jois was born on Guru Purnima (the full moon day in the month of Guru, which normally falls in July) in 1915 in the village of Kowshika, close to Hassan, in the Karnataka state. Since his first arrival in Mysore he went through exceeding difficulties. He knew neither friends nor relatives in the town, and was forced to beg for food during his first few years of staying there. Due to his little knowledge in Yoga, his luck eventually changed and he started doing demonstrations of Yoga at the College as well as visit the home of the Maharaja. Pattabhi Jois was eventually given the post of Yoga Teacher to the students at the Sanskrit College in 1937. He retained this post until 1973. While being a teacher he was also able to pursue his own studies and received a Vidvan degree (the equivalent of a Western MA degree) in Vedanta from the same college.

Pattabhi Jois claims that the style of Yoga he teaches is exactly the same as what Krishnamacharya taught him. He openly admits that he has refined some of the sequences of postures given him by Krishnamacharya and grouped them into a clearer, systematic development of sequence. This he claims was something that took place after years of personal observation and experience from the practice, all for the sake of facilitating a greater opening in the body and paving the way for a more integrated experience of Yoga to take place. What is particular with the Ashtanga Yoga method taught by Pattabhi Jois is that the student is gradually led through a set sequence of postures step by step. Each student is first taught the sun salutations, which Pattabhi Jois claims is the very foundation to the practice. Then gradually the student will be introduced to new postures, but only if they display a level of proficiency in the basic movements of what they have been learning. Pattabhi Jois adamantly claims that the method he represents gradually will awaken a greater receptivity to spirit from within, but the primary steps are first to cleanse the body of its physical imbalances. He claims further it will serve no purpose for somebody to perform difficult postures unless their body/mind/nervous system has been prepared for it. Every beginner is therefore first introduced to the basic components of the practice constituting the sun salutations and standing postures. This is in order to prepare the body for the seated (asana) sequence to follow. What is further significant with this form of practice is that, in the beginning, it may appear extremely physically demanding because an intense inner heat may be produced, and the practitioner may equally be subject to a profuse level of sweating. This usually takes place in the early stages and is supposed to act as a cleansing mechanism for the body/mind/nervous system in order to free up imbalances from within and gradually awaken the body and mind to a greater receptivity of Yoga. This form of exercise is by far the most physically challenging of all the modern schools of Yoga, but Pattabhi Jois claims the goal is not physical but of a spiritual nature–that one therefore does not have to be to be an athlete to practice this method, but greater strength and flexibility is a natural outcome that will follow.

According to this system, there are six different sequences of postures a person may learn, also known as “series.” They have an average of 25 asanas each. Only a handful of people in the world are proficient above the third level and have ever attempted any of the later sequences involving advanced contortionist exercises with deep backbends, twists and intense stretches having a radical impact on the organs and body/mind/nervous system. The policy at the Ashtanga Yoga Research Institute (AYRI), where Pattabhi Jois is the Director, is to slowly and gradually build up the capability of each student. Nobody is therefore taught advanced postures unless they have spent a minimum of 3 to 5 years consolidating the practice and showing a reasonable level of consistency and dedication. The final and penultimate sequences are both shrouded in a lot of mystery, particularly the last one, and only one living person in the world has been introduced to it–Sharath Rangaswamy, the grandson of Pattabhi Jois. According to hearsay, some of the “exercises” here involve stopping your own heartbeat and other extreme levels of physical control over the muscles as well as the inner organs.

These advanced exercises are, of course, far removed from what is normally taught in health clubs, fitness centers and yoga studios around the world, but what is interesting to note is that much of the “Power Yoga” and other styles of “Fitness Yoga” that suddenly flourished in the gyms and health clubs around the world 10 to 20 years ago all bear reference to the Primary Series, the first sequence taught by the AYRI. This series, known as Yoga Cikitsa (Yoga for Health) in Sanskrit, attempts to realign and balance the gross physical body by first facilitating an awakening to greater health and then increase the flow of energy throughout the body by opening up stagnation in the ankles, knees, hips and spine for improved circulation and well being.

The Second Series, Nadhi Shodhana (The Nerve Purifier) works deeper by trying to create more length in the spine and strengthen the organs further. Here we find many back-opening poses, twists, legs-behind-the-head sequence, simple arm balances, more twists followed by a headstand variation at the end to balance the new flow of energy in the central axis and increase the flow of blood to the brain.

The last four series are the Advanced A, B, C, and D sequences–in Sanskrit called the Sthira Bhaga (Centering of Strength). These postures aim to center the body/mind/nervous system in a greater steadiness from within, but these postures should only be attempted after years of practice. Without a solid grounding in the practice it is easy to cause more harm than good to the body/mind/nervous system from the sheer intensity of the postures. This sequence is also called the “Rishi” sequence since names from many of the famous sages of the Vedas are found here. The postures from the A and B sequences consist of postures with increasing difficulty such as leg-behind-the-head variations, strenuous arm-balances, twists and deep, intense backbends. The average amount of time to complete each sequence referred to above is usually two to three year’s minimum. Some students never make an attempt beyond the Primary Series, but what all practitioners seem to have in common is the love for their practice and the embodiment of greater health and well being that seem to shine vibrantly through their skin and eyes and manifest clearly on their faces.

As normal people in general, practitioners of this method also may be caught up in various vices and addictions when they first come to the practice. However, for the majority, this usually becomes neutralized in the increased level of receptivity to a greater source of being from within–for when one glimpses this “inner being,” all external sense impression and stimuli seem to dull in comparison. Pattabhi Jois urges his students to pay more attention to this inner receptivity of ‘being” in matters of diet, health, nutrition, etc. “Find out what works for you,” he says. “A pure body naturally knows what is good for it! Listen from within and you will gradually be able to know for yourself what is good or less beneficial for you.” The significant feature of these simple exercises is that people certainly improve their health and well being, but also seem to find a new approach to life which involves a greater receptivity to something internally profound. For anybody who thought this method was all about building a new body–toned, trim and well-shaped, like a Greek god–Pattabhi Jois’s immediate reply is:

“Yoga is not physical, very wrong. Hatha Yoga can indeed be used as external exercises only, but that is not the ultimate benefit of Yoga. Yoga can go very deep, deep and touch the soul of man. When Yoga is performed in the right way, over a long period of time, the nervous system is purified, and so is the mind. When you take asana properly, for a long time, pratyahara, dharana and dhyana naturally becomes more established and then greater clarity of mind and increased receptivity of self is brought about.” [From an interview in Namarupa Magazine entitled “3 Gurus,” Autumn 2004]

Many people even criticize the teachings of Pattabhi Jois as mere callisthenic exercises. However Pattabhi Jois’s message to his students is very clear: “Practice, practice, and all is coming!” By this statement he means that for a greater experience of Yoga to come about, “practice” is essential and without “practice” it is almost impossible to penetrate into a greater understanding of Yoga. The greater essence of Yoga is difficult to define in name and form, but proper practice and method may awaken our receptivity to this inner being; hence, we may come to experience how it lives and observes all the movement of the body/mind/sense organs rather than being caught up within them. Pattabhi Jois believes firmly that a proper asana practice is of crucial importance in this process because our body and mind operate according to fixed patterns of their own, and the easiest way to break this impact is to have a consistent practice that will free up layers of tension from within and facilitate an increased level of inner clarity, health and freedom. Nobody claims that this process is easy, but for those that stay consistent with their practice, an increased inner receptivity is bound to follow that brings about further rewards. One may, of course, argue the relevance of this proposal, but it is interesting to observe the increasing number of people flocking to this practice from all over the world. One may therefore safely assume there are certain benefits–spiritual as well as physical.

Pattabhi Jois himself is not a great talker. Although a traditionally trained Pundit, he is not too keen on articulating his views on Yoga to the general public. Repeatedly he says it takes a long time to experience the deeper meanings of Yoga and he often informs us that there are no “quick fixes.” His only book, The Yoga Mala (1956 published in Kannada, first translated to English in 1999), remains his only publication next to “Surya Namaskara” (a small booklet on the importance of sun salutations, published 2005). His probably most famous quote, which sums up the tradition, reads: “Ashtanga Yoga is 1% theory and 99% practice.” “Guruji,” as his students affectionately call Pattabhi Jois, does not hold any teacher training courses or advanced seminars for his students. His only requirement is that people practice and aim to learn properly the method he is teaching. Then after years of practice, if the students show increased proficiency and greater understanding of what they’ve been taught, he may eventually give them his blessing to teach. Only one hundred and fifty people in the world are estimated to have received this “Authorization,” as it is called, yet still thousands of people are teaching his method all over the world. To all those who capitalize on his method without proper training, Pattabhi Jois just smiles and says, “Let other teacher be there, but I hope their students finally one day will get what they deserve!”

Being an orthodox Brahmin and a follower of the Advaita tradition first propagated by Sri Shankaracharya, authenticity and proper commitment to learning the tradition properly is of paramount importance to Pattabhi Jois. He displays an unwavering faith in the teachings of the Vedas: “Everything is there,” he says, “We just need to recover the understanding within our own minds. Then we can truly understand the greatness of our forefathers.” It is indeed hard to argue about the authenticity of the Yoga method that he teaches, but it stands to reason that the method he is teaching is very similar to what Krishnamacharya taught him during his time in Mysore. BKS Iyengar, as well as the publications of the Krishnamacharya Yoga Mandiram (KYM), confirm to a similar style of teaching that Krishnamacharya was engaged with for this period. Whether these postures are the same as Krishnamacharya was taught from Ràma Mohan Brahmacàri is open to further debate, but a thorough research into the whereabouts of the Yoga Kurunta would certainly bring new light into the origins of this tradition. But suffice to say, this physical practice of Yoga has brought a whole new interest to the subject of Yoga all over the world. The actual impact of the practice and the effect it has on its various practitioners is for each individual to explore, but it seems to be apparent that this particular practice makes people relate to yoga in a new, different way. According to Pattabhi Joi,s it was never really about the physical body, but rather the inner experiencer of it all which is gradually set free and becomes more manifest in the process.

Pattabhi Jois echoes Patanjali when he calls his system “Ashtanga Yoga.” In the second chapter of Patanjali’s Yoga Sutras, “The Sadhana Pada,” we first find reference to this name, Ashta-anga, the “eight limbs”‘ as the eight practical integrated steps leading to a greater gradual awakening of Yoga up to the final transcending state of Samadhi. Pattabhi Jois, however repeatedly claims that the very essence of Yoga must be more than theoretical knowledge: it must transcend it, and for this we are dependent on practical experience to integrate our awareness into something more substantial than just thought. He therefore easily smiles as in fatigue, whenever people become too keen to project their various ideas on Yoga without having created a proper foundation to receive it. “The practice takes time,” he repeatedly claims, but says further: “When you experience it for yourself you will come to know that it is rea.l” He therefore refrains from getting into too much philosophical argumentation about the relevance of this practice and rather lives by the dictum: “Practice, practice, and all is coming!” However, whenever we challenge him and demand a clearer articulation of his views on the subject of Yoga on what is practice and what is it really for, he is always there to give his steady opinion:

“The practice of asanas and pranayama is learning to control the body and the senses so the inner light may come forth. That light is the same for the whole world and it is possible for man to experience this light, his own Self through correct Yoga practice. This is the natural outcome of a good practice and one will gradually learn to control the mind because one eventually will come to experience the very support of it. But the mind is indeed very difficult to control, but everything is made possible with right practice. We must therefore first and foremost practice, practice, practice for any real understanding of Yoga to take place. Then eventually we will be able to break the fixed patterns of the mind and taste the greater underlying support of it all. Philosophy is of course important, but if not connected and grounded in truth and practicality, what is it really for? Just endless talking exhausting our minds! Practice is the foundation for the actual understanding of philosophy. Unless things become practical and we can come to experience it, for what use is it? “Yoga hinam katham moksam bhavati druvam.” Without Yoga (practical experience), how can the pursuit of liberation ever be possible?” [Namarupa Magazine, 2004]

It is apparent from the above that the so-called Ashtanga Yoga method facilitated by Pattabhi Jois is an inquiry into the essence of Self and the very substratum of our being rather than just physical exercises of fitness. The actual application and value of this particular method is, of course, open to great debate, but it is difficult indeed to access the actual relevance of what he says without proper commitment to the practice over time in order to experience for oneself the actual impact of it. Seeing the growing interest in this practice all over the world, we can safely assume that this particular practice does something to the individual that seems to transcend the mere desire for fitness and greater flexibility. It rather seems to create more space and greater awareness from within about this very life force situated within us. And come to think of it, that may be quite conducive for a proper integration in Yoga.