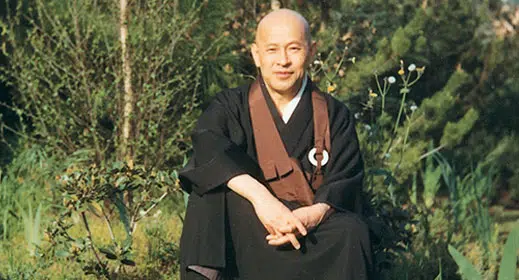

Daisetsu Teitaro Suzuki: was a Japanese-born scholar of Zen and Japanese culture who essentially introduced the West to Zen and Mahayana Buddhism through his many published works.

A lay practitioner of Rinzai Zen—Suzuki ‘s writings influenced such thinkers as Erich Fromm, Carl Jung, Thomas Merton, Karl Jaspers, Arnold Toynbee, Martin Heidegger, Gabriel Marcel, and many others. Suzuki’s contribution to Western understanding of Zen Buddhism is significant, considering that he was not a priest himself.

Daisetsu Teitaro Suzuki was born as Teitaro Suzuki on October 8, 1870 in Kanazawa, Japan to a family of the samurai class. He was the son of a physician who was very partial to the Chinese classics and a mother who was an observant adherent to the Jodo Shinshu faith. During the Meiji restoration the privileges samurai class families enjoyed had been abolished. Suzuki was therefore raised in discreet poverty. In 1876 Suzuki’s father died, making it difficult for his widowed mother to raise the family. He attended a local high school where he became childhood friends with Nishida Kitaro, an equally significant thinker in terms of Zen and Western philosophy. To make ends meet his mother rented their home to boarders and, at age 18, Suzuki landed a job teaching math, reading, writing and English in a small fishing village. Suzuki also began Zen training under Setsumon-roshi before finishing high school at Kokutai-ji.

In 1891 he entered Tokyo Senmon Gakko, today’s Waseda University—he also continued his training with the Rinzai master Imakita Kosen. Following the deaths of his mother and Imakita Kosen in 1892, Suzuki began studies at the Imperial University in Tokyo and continued his Zen training with Shaku Soen. (Kosen-roshi’s Dharma heir). Though he did not ordain as a monk, Suzuki spent the next four years as a lay student at Engakuji training with Shaku S?en. Following his completion of the Mu koan during a rohatsu sesshin, Shaku Soen gave him the lay Buddhist name Daisetsu—which means ‘Great Simplicity.’ At times Suzuki would later joke that the true meaning of his name was ‘Great Stupidity.’

In 1893 Shaku Soen was chosen as one of those to attend the World Parliament of Religions in Chicago. Suzuki was brought along with him to serve as an interpreter. Shaku S?en was an acquaintance of Paul Carus, a Japanophile who owned a publishing house known as The Open Court Publishing Company based in LaSalle, Illinois. Upon the recommendation of Shaku Soen, Suzuki returned to the United States in 1897—employed as Paul’s assistant. He boarded in Carus’s home and helped around the house in addition to his employment. He helped Carus with a translation of the classic Chinese text the Tao Te Ching, painstakingly translating each character. Suzuki later remarked on how he was displeased with the final product, given that he was a Japanese translating Chinese and that Carus was a German writing in English. He found that the translation missed the mark, boiling down complex Chinese ideas into abstract concepts which failed to capture the intended meaning.

While his main task with The Open Court Publishing Company was in the translation department, he also typed and read proofs and dealt with photography. Following the translation of the Tao Te Ching, Suzuki began his translation of Ashva-ghosha’s The Awakening of Faith in the Mahayana (1901). He also began what would become his own first book in English while with Carus—Outlines of Mahayana Buddhism (1907). In 1906 Suzuki met his future wife—Beatrice Erskine Hahn Lane Suzuki—at a lecture given by his teacher Shaku Soen during his return trip of that year. Following the publication of his first book, in 1908, Suzuki left The Open Court Publishing Company and went to London to study the philosophy of Emanuel Swedenborg.

In 1910 Suzuki began teaching in Tokyo at the Peers’ School and, in 1911, he and Beatrice married—moving to Japan full-time. In 1921 Suzuki was given a professorship at Otani University in Kyoto and he left the Peers’ School that following year. His work Essays in Zen Buddhism was published in 1927 and, in the coming years, so too were more articles and publications targeting an English audience. Also in 1927 Beatrice and Suzuki started up the Eastern Buddhist, a Buddhist journal published in English out of Kyoto. His works had a major impact overseas, resulting in his having become the preeminent scholar on Zen and Japanese culture in Europe and the United States. While looking at his works from where we sit today, Suzuki’s body of literature on Zen may seem overly academic—this despite the fact that much of what he wrote came from the ground of his own experience.

Suzuki spent most of his time in Japan after leaving The Open Court Publishing Company and his visits to the West were irregular. He did return in 1936 and remain until World War II. Later in 1950, at age 80, Suzuki returned again to the United States and spent much of the next decade teaching and lecturing in American universities like Colombia, Harvard; he also lectured at the University of Mexico and did the Eranos conferences in Sweden. Also worthy of note, Suzuki became president of the Cambridge Buddhist Association and, in 1956, the Zen Studies Society of New York was established to support his ongoing work. When he was 90 years old Suzuki took part in a four-week tour of India as an official State Guest. At age 94 he returned to New York, where he met the Cistercian Catholic monk Thomas Merton; the two began a dialogue on Zen and Christianity via letters. He also attended the East-West Philosopher’s Conference in Honolulu.