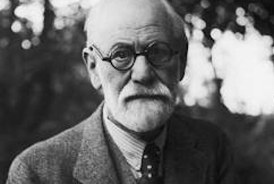

by Debbie Hagan: Eighty years old, sick with cancer, and reeling from the Nazis’ takeover of his beloved Vienna, Sigmund Freud, in 1936, faced a harsh reality:  he had to leave. But where would he go, and how would he get there? What would he do with his art and book collections? How could he protect his family? He was invited to the United States, but he promptly turned that down. He had remembered his lecture at Clark University, in Worcester, Massachusetts, where had received an honorary doctorate degree. The experience left him referring to the country overall as “a giant mistake.” He’d rather take his chances with the Germans.

he had to leave. But where would he go, and how would he get there? What would he do with his art and book collections? How could he protect his family? He was invited to the United States, but he promptly turned that down. He had remembered his lecture at Clark University, in Worcester, Massachusetts, where had received an honorary doctorate degree. The experience left him referring to the country overall as “a giant mistake.” He’d rather take his chances with the Germans.

Thus, The Escape of Sigmund Freud, written by David Cohen, historical writer, filmmaker and psychologist, unravels a strange and often overlooked bit of history in just how Freud managed to leave occupied Austria, when Hermann Göebbels and Joseph Himmler had set out to kill psychoanalysts, particularly Jewish ones.

By 1925, Freud was an international celebrity, the father of psychoanalysis, and author of groundbreaking theories on the unconscious mind, repression, and dreams. As well, he headed the International Psychoanalytic Publishing House, which he had started in 1919. In his therapy practice, he charged $25 an hour for his services–an astronomical sum back then, the equivalent today of nearly $4,000 an hour. Thus, his clients came from rarefied circles, which included the colorful Princess Marie Bonaparte, socialite and great-granddaughter of Napoleon, who became Freud’s close friend and advocate.

However, the world as Freud knew it had dramatically changed since Adolf Hitler had seized power and forced his ideology concerning racial cleansing onto Germany, then Austria. Hitler was appalled to learn that most German doctors were Jewish. “The worst statistics from Nazis’ point of view were pediatricians: 72 percent were Jewish,” writes Cohen. Certainly most psychoanalysts were Jewish. Thus, in 1936, Matthias Göering (cousin of Hermann Göering) assumed leadership over the German General Medical Society for Psychotherapy, renouncing Jewish psychoanalysts. Göering had their property and assets seized, which included Freud’s publishing company.

Harsh as these actions were, the Nazis couldn’t escape the fact that Freud was a well-connected, international figure, who they grudgingly had to respect. Freud did have friends throughout the world, such as William Bullitt, the American ambassador in Paris, and President Roosevelt, who telegrammed Hitler, warning him that any harm done to Freud would be considered a deplorable act. Still it didn’t stop Nazis from hanging swastikas on Freud’s stoop or the Gestapo from harassing him, claiming that he had not paid his taxes and his publishing company had outstanding debt. Thus, military police confiscated the family’s cash and passports. These actions reached a climax when the Gestapo arrested Freud’s daughter Anna, a noted analyst in her own right, which shook Freud into a stark reality: His life in Vienna was over.

What ultimately happens is best read in Cohen’s book, but suffice to say Freud was lucky to have influential friends, money stashed in secret accounts, and an unlikely supporter– a German officer who out of character developed a conscience and looked the other way as Freud left. Thus, the Freud family (including his daughter, Anna, his wife, Martha, and their faithful housekeeper, Paula), fled to Britain. They toted along Freud’s famous couch, some of his books, and many objets d’art.

Four of Freud’s sisters stayed behind. Even though Freud made many attempts to contact them, he never succeeded. Years after his death, researchers would discover that three had died in concentration camps. The fourth most likely died of malnutrition. More details about their deaths and other circumstances surrounding the Freuds and their escape may exist in correspondence sequestered in boxes at the Library of Congress that remain restricted until 2050 and 2057. Other boxes, particularly those involving Marie Bonaparte, supposedly are sealed for eternity. One can only assume they must hold privileged doctor-patient information.

Even so, there’s no shortage of research in this book. In spite of being a relatively slim book, it is dense with facts. Cohen throws so many names at readers that he offers a who’s who guide in the back to help keep the various characters straight.

Though the title of the book is The Escape of Sigmund Freud, less than a fourth of the book really deals with his escape. If I have one quibble with the author it’s about this. Rather than rehashing a lot of German and European history that most people know only too well, I would have liked for him to have given us more details on Freud’s flight from Vienna, which turns out to be a rather complex and amazing feat that deserves more attention and detail.

Even so, the story is remarkable and gives further credence to the old saying that truth is stranger than fiction. This book will appeal to anyone interested in early psychotherapy history and the strange and complicated life of Sigmund Freud.