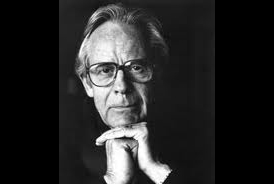

by Stephen A. Diamond, Ph.D.: May was one of the founders and leaders (along with Carl Rogers and Abraham Maslow) of the humanistic psychology movement–the so-called Third Wave in psychology, the first being psychoanalysis, behaviorism being the second– and the pre-eminent exponent of existential therapy in particular. It was his groundbreaking book Existence: A New Dimension in Psychiatry and Psychology (1958), co-edited with Ernest Angel and Henri Ellenberger, that introduced European existential analysis to the American psychotherapy scene. (See my prior post.) Dr. May is considered to be the “father” of existential psychotherapy.

of the humanistic psychology movement–the so-called Third Wave in psychology, the first being psychoanalysis, behaviorism being the second– and the pre-eminent exponent of existential therapy in particular. It was his groundbreaking book Existence: A New Dimension in Psychiatry and Psychology (1958), co-edited with Ernest Angel and Henri Ellenberger, that introduced European existential analysis to the American psychotherapy scene. (See my prior post.) Dr. May is considered to be the “father” of existential psychotherapy.

Soon there will be a much-deserved and long-awaited biography of Rollo May published by Oxford University Press, painstakingly researched over the past two decades by historian and scholar Robert Abzug of the University of Texas at Austin. (Professor Abzug’s abridged edition of psychologist William James’ classic text The Varieties of Religious Experience will be published in 2012.) In anticipation of this forthcoming momentous literary tribute, let me relate a few of my own personal memories of Dr. May here for readers of Psychology Today.

I first met Rollo May in 1980. I was twenty-nine years old and he was seventy-one. I called him one day out of the blue. He didn’t know me from Adam. I was at that time a clinical psychology graduate student in the San Francisco Bay Area doing my pre-doctoral internship, and just starting to think about topics for my doctoral dissertation. Having read a couple of his books by then, I was an avid admirer of May’s writing and in search of a serious mentor for my budding identity as a psychologist. Dr. May was at that time one of the most prominent and esteemed psychologists in the world, which made initiating contact with him an intimidating prospect. But I took the risk of being rejected and, with much trepidation, made the fateful phone call. My courage (or perhaps hubris) paid off. May was not only gracious in receiving my request to become his pupil, but in that first conversation, assigned me three books to read prior to talking again, based on my having expressed my intention to write a dissertation on the general topic of anger and psychotherapy. These three extraordinary books were Ernest Becker’s The Denial of Death (1973), The Courage to Be (1952) by May’s former mentor existential theologian Paul Tillich, and his own bestselling Love and Will. Having been happily given these unexpected marching orders, I rushed right out and purchased all three paperbacks and started reading. My tutelage under Rollo May had abruptly begun.

About two weeks later, I received a surprising call from Dr. May, inviting me to attend a clinical supervision seminar he was conducting for psychology interns training at the Langley Porter Neuropsychiatric Institute. He explained that since I too was doing a pre-doctoral internship, albeit elsewhere, and already a licensed Master’s level mental health professional, I would be welcome to join the newly forming group, scheduled to meet every other week at his home in Tiburon, just north of the Golden Gate Bridge. Needless to say, I jumped at the golden opportunity. And golden it was, since for ten weeks we trainees had the relatively rarefied opportunity to sit together in Rollo May’s living room–tasteful modern art, fluffy white Greek flokati rug, comfortable contemporary furniture–and receive supervision from this renowned master therapist. What I remember most about this heady experience (some of which was filmed) was May’sgenerosity, openness, kindness, concern and curiosity about our cases, and his keen focus on how we were relating to our patients, both as clinicians and caring human beings. Oh–and of course, his silk ascot. Rollo was “old school” in some ways, but surprisingly avant garde in others.

At the conclusion of that memorable clinical supervision group, having by then completed my earlier assigned readings, I excitedly told Rollo of my powerful epiphany arising from reading hisLove and Will. It was for me a major revelation, one of those “aha!” or “eureka” moments. I had discovered synchronistically in his seminal chapters on the daimoniccontained therein precisely what I was seeking: the perfect theoretical vehicle for conceptualizing the role of anger and rage in psychopathology, violence, evil and creativity. When I initially told him I wanted to do a dissertation incorporating his controversial concept of the “daimonic,” he gave me a kind of concerned, cautionary, almost pitying look, warning that people have difficulty comprehending and relating to his idea of the daimonic. Undaunted, I decided to move ahead. Informing him of my final decision, in a subsequent letter, he responded that he felt the daimonic to be a “superb topic” for my dissertation, and fully supported the project. Later, I asked whether he would be willing to formally serve on my dissertation committee. Reluctant to take on too much responsibility and due to the dissertation’s emphasis on his own work, Rollo agreed to be my fourth, unofficial dissertation advisor. This marked the start of an ongoing correspondence by letter ( this was before e-mail) and series of meetings regarding the dissertation and its progress over the next couple of years until its eventual completion and approval in 1982. (The final title of the dissertation was “The Daimonic and Depth Psychology: Rollo May’s Contribution Reclarified.” )

Midway in my writing, I found myself frustrated and bored with the labor-intensive, tedious dissertation process, and complained about this to Rollo in one of my letters. To closely paraphrase from memory his powerfully therapeutic response: “Writing is tedious for everyone. Thomas Mann once said that writing is something that gets more difficult the more you do of it. But there can be moments of ecstasy that will make the whole process worthwhile.” This succinct comment, coming from someone who had by then published a dozen erudite and critically-acclaimed books, provided the inspiration I needed to persevere and complete the arduous, detailed, sometimes seemingly impossible Herculean labor.

After receiving my Ph.D. in Clinical Psychology, I continued corresponding with Rollo about turning the dissertation into a book. He was always very supportive of this next venture. And of my professional development in general. (For example, he later sponsored my application for membership in the American Psychological Association.) But I, having gotten busy with my own practice, decided, after a few frustrating, half-hearted efforts to find a publisher, to put that project on the back burner. Meanwhile, I started to submit and have published a series of essays in the San Francisco Jung Institute Library Journal. The first of these, “Finding Beauty,” appeared in 1986, a review of May’s then recently released and semi-autobiographical My Quest for Beauty (1985). He read that review and asked whether his publisher could have permission to quote from it for a blurb on the back cover of his then newly revised Paulus: Tillich as Spiritual Teacher (1988). Of course, permission was gladly granted. Another article soon followed (1987) in which he took interest, a review of Acts of Will: The LIfe and Work of Otto Rank by E.J. Lieberman titled “Rediscovering Rank,” Rank’s then still relatively obscure psychology being highly valued by both May and Becker. Dr. May years later contributed a Foreword to Robert Kramer’s A Psychology of Difference: The American Lectures [of] Otto Rank (1996, Princeton University Press).

During 1990, May unselfishly took precious time out from working intensively on what would turn out to be his last major work, The Cry for Myth, to meet me for lunch at one of his favorite local restaurants. Over good seafood, a glass of wine, and a gorgeous view of a glittering San Francisco Bay, we kicked around a new article I was working on, derived from my dissertation: a critical review of M. Scott Peck’s People of the Lie: The Hope for Healing Human Evil(1983 ). This essay, titled “The Psychology of Evil,” contrasted Peck’s born-again Christian psychology of evil with May’s secular existential perspective of evil rooted in his concept of the daimonic. Though I expressed reticence to publish something so critical of someone of Peck’s popularity, May encouraged me to do so, and the piece was published later that year. Soon thereafter, he very thoughtfully sent me a pre-publication galley of his now completed The Cry for Myth, perhaps hoping I would write an early review, which unfortunately for some reason I never did until years later. (See that very brief belated review here at amazon.com.)

round 1991, I started teaching and eventually became assistant clinical professor at Pacific Graduate School of Psychology (now Palo Alto University). Coincidentally, Dr. May was invited to give a public lecture there, before which we had a formal reception and dined together with Dr. Irvin Yalom of Stanford University, his wife, and several other faculty members. It became painfully apparent that May’s health had started to fail, and he would intermittently fall into brief periods of mental disorientation and confusion. By that time, after a decade ofprocrastination, I found the requisite courage and motivation to take up in earnest the renewed quest for a publisher. Fortunately, after carefully crafting a revised book proposal and some extensive searching, I finally did. The State University of New York Press (SUNY Press) offered me a contract to write the book as part of their Series in the Philosophy of Psychology (edited by Michael Washburn), and Dr. May agreed to contribute a Foreword. He seemed pleased I had at long last found a publisher and the will to proceed.

I met with Rollo at his home on the final day of 1993. It was New Year’s Eve, and we talked for an hour or so that brisk December afternoon about my book and its progress. He was in good spirits, energetic and quite lucid, albeit a bit frail. I told him about a dream I had, and he enthusiastically suggested we analyze it further, though we had no time to do so. That turned out to be the last time I actually saw Rollo May, but not the last I heard from him. During the New Year, we continued to communicate about my book. Many months later I received a strange message from Rollo on my office answering machine. To paraphrase from memoryonce more, he said he had been up in Heaven for a while visiting with the angels, but now was back here on Earth and ready to talk with me. Concerned, I immediately called his home and spoke with his wife, Georgia, who confirmed he had recently suffered a serious crisis and was still too ill to receive visitors.

Sadly, though we kept him apprised of its progress throughout most of 1994, Rollo never got to see the book’s publication. Rollo Reece May died in October at the ripe age of eighty-five. I attended the funeral held at Grace Cathedral on Nob Hill in San Francisco, as did so many of his family, friends and close colleagues like Sam Keen, Tom Greening and Irv Yalom. My revised dissertation, totally rewritten and retitled Anger, Madness, and the Daimonic: The Psychological Genesis of Violence, Evil, and Creativity, was finally released in Fall of 1996, two full years after May’s death, and dedicated to his memory.

I was extremely lucky to be a pupil and protege of Rollo May. To be mentored by a psychologist and psychotherapist of his extraordinary caliber and experience. And I have been lucky to have had other equally influential mentors in my life, both male and female, including early on, my father, Albert, who passed away in 2010. What is a mentor? Consider this definition found on Wikipedia: “Mentoring entails informal communication, usually face-to-face and during a sustained period of time, between a person who is perceived to have greater relevant knowledge, wisdom, or experience (the mentor) and a person who is perceived to have less (the protégé).” The mentor must possess (or appear to possess) knowledge or skills that the apprentice or protege seeks, be it spiritual, philosophical or psychological. The relationship between guru and disciple is one example of spiritual mentorship. In this sense, psychotherapy, at its best, is a form of mentoring: the psychologist is seen, by virtue of his or her training and experience, as someone with superior insight into the human psyche and soul than most and who can therefore help the patient with his or her psychospiritual problems partly by sharing this knowledge. (See my prior posts on clinical wisdom.) This is what real psychotherapy is all about. (See my prior post.) For me, for instance, my own analysts served as superb mentors, spiritual guides and professional role models at different stages of my life, and I do my best to fulfill this role for my own patients, supervisees and students.

In The Odyssey, Mentor was the trusted old teacher and wiseadvisor to Telemachus, son of Odysseus. Socrates served as mentor to his students. Whether in philosophy, filmmaking, mathematics, medicine or psychology, the power and importance of professional mentors cannot be underestimated. C.G. Jung said that when he met the senior Sigmund Freud, this had been his first true encounter with greatness. (See myprior post.) For him, indeed for both men in that case, it was a life changing event. I feel similarly about meeting Rollo May. For me, Rollo May, the eminent existential psychologist and psychoanalyst forty-two years my senior, was a fatherly figure and professional role model, a man of high intellect, penetrating insight and deep compassion for the human condition. A person, who, as he himself put it, had “done a lot with his life,” who had “walked with giants.”

May, much like Jung (see my prior post), had experienced and transformatively worked himself through a “nervous breakdown” during his twenties when teaching English in Greece, studied with Alfred Adler in Vienna, attended seminary to briefly become a Congregational minister in New Jersey, survived tuberculosis in an existential mid-life crisis, earned the first Ph.D. in Clinical Psychology ever granted by Columbia University, developed and maintained a close connection with theologian Paul Tillich (read aninterview of May about Tillich), studied with Erich Fromm and received analysis from Frieda Fromm-Reichman (the therapist depicted in the book I Never Promised You a Rose Garden), introduced the tenets of existential analysis to American clinicians, normalized the phenomenon of existential or ontological anxiety, humanized the practice ofpsychotherapy, and was one of the first psychoanalysts (following Jung and Rank) to recognize the need for a better psychological theory and understanding of the problem of evil and to integrate spirituality into clinical practice.

Rollo was a real revolutionary. During his brilliantly creative career, Rollo May influenced thousands of clinicians, including James Bugental, Irvin Yalom, Kirk Schneider, Ed Mendelowitz and many others such as myself. To me, Rollo May was equal parts father, therapist, teacher, priest, wise old man. He gave me a new way of seeing myself, the world, the psyche. Of appreciating life’s beauty and mystery. And, most of all, he cultivated in me by example an acceptance of thedaimonic potentialities in myself and others as well as fostering the courage to create and express myself despite anxieties, doubts and fears. He gave me my first glimpse of greatness. And inspired me to push far beyond my own fateful limitations, to exercise my freedom, to find and fulfill my destiny.

Dr. Rollo May (1909-1994) was a clinical psychologist, neo-Freudian psychoanalyst, and existential psychotherapist. (See brief video clipshere and here.) He authored some fifteen books, including The Art of Counseling (1939), The Meaning of Anxiety (1951), Power and Innocence (1972), The Courage To Create (1973), Freedom and Destiny (1981), The Cry for Myth ((1991) and Love and Will (1969), the latter being his magnum opus in my opinion.