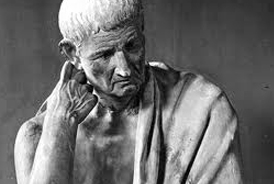

by PM Dunn: Aristotle was one of the greatest philosophers and scientists the world has ever seen.  He was born in 384bc at Stagirus, a Greek seaport on the coast of Thrace. His father, Nichomachus, court physician to King Amyntus II of Macedon, died while he was still a boy, and his guardian, Proxenus, sent him to complete his education at the age of 17 in Plato’s Academy in Athens.

He was born in 384bc at Stagirus, a Greek seaport on the coast of Thrace. His father, Nichomachus, court physician to King Amyntus II of Macedon, died while he was still a boy, and his guardian, Proxenus, sent him to complete his education at the age of 17 in Plato’s Academy in Athens.

He remained there for the next 20 years, first as a pupil and later as a teacher. Plato and Aristotle recognised each other’s outstanding qualities, but they had frequent arguments and disagreements. Whereas Plato believed that reality existed in ideas, knowable only through reflection and inspiration, Aristotle saw ultimate reality in physical objects, knowable through the experience of the five senses. He believed that every problem had an objective solution. His was a scientific approach. Of his master he wrote: “Plato is my friend but truth is much more”.

When Plato died in 347 bc, Aristotle, aged 37, was not appointed to succeed him. Perhaps his differences with Plato were too great. He then left Athens to spend the next five years in Asia Minor at the court of Hermeas, ruler of Atarneus in Mysia, whose niece and adopted daughter, Pythias, he married. In later life he married a second time a woman named Perpyllis, who bore him a son, named Nichomachus after his father. In Asia Minor and later in Mytilene (Lesbos), Aristotle pursued his studies in biology and natural history until, in 342 bc, he was recalled to Macedon by Phillip II (King Amyntas’ son) to act as tutor to his 14 year old son Alexander. Seven years later, in 336 bc, Phillip was assassinated, and the following year Alexander, now king, set out on his conquest of the Persian Empire. At this time, Aristotle at the age of 49 returned to Athens to found his own school of philosophy, The Lyceum. It was nicknamed the “peripatetic school” because of Aristotle’s practice of lecturing his students while walking around the school’s garden. Besides teaching, Aristotle amassed a large collection of manuscripts, which later found their way to the library in Alexandria. He also cultivated a botanical garden. His disciple and successor, Theophrastus of Eresos (370–287 bc) later based his De historia plantarum on this garden, listing 500 plants.

When news of Alexander’s death in Babylon reached Athens in 323 bc, Aristotle, fearing an anti‐Macedonian reaction, prudently withdrew from Athens to Chalcis in Euboea, his mother’s home town. There the following year, 322 bc, he died of a stomach illness. He was 62.

Aristotle’s lectures were collected into nearly 150 volumes and represented an encyclopaedia of the knowledge of his day, much of it indeed his own contribution. Unfortunately, less than a third of his writings have survived. Although Aristotle’s most important work was on biology, he also dealt with logic, metaphysics, psychology, meteorology, politics, literary criticism, poetry, drama, and ethics. Although he was not a doctor, his contributions to medicine were immense. He was the first to treat systematically the fields of botany, zoology, anatomy, embryology, teratology, and physiology. Aristotle was assisted by his great faith in nature, writing: “In all things of nature there is something of the marvellous”, “Nature does nothing uselessly”, and “If one way be better than another, that you may be sure is nature’s way.”

Starting as he did virtually from scratch, it is hardly surprising that some of Aristotle’s explanations as to how the human body functioned were incorrect. For instance, like Hippocrates, he subscribed to the humeral theory of disease holding that there were four primary fundamental “qualities” in life: hot, cold, wet, and dry. These met in binary combination to constitute the four “elements”: earth, air, fire, and water, represented respectively by black bile, yellow bile, blood, and phlegm. The body was thought to be composed of these “humours”, which were responsible for the temperaments: melancholy, choleric, sanguine, and phlegmatic. Disorders of the human body were thought to be caused by an upset in the balance of these humours.1 Unfortunately his fame and authority were so great that these concepts persisted for 2000 years until overturned after the Renaissance in the 16th century. This was hardly the fault of Aristotle, who was himself no believer in blind obedience to authority.

Aristotle was a great classifier and codifier. In his effort to develop a strong taxonomic scheme, he noticed important similarities and differences between various zoological forms. He arranged these upon a basis of increasing perfection, extending from lower to higher animals. In its way, this was a theory of evolution. He also developed a coherent theory of generation, believing that the mammalian egg was formed in the uterus as a result of the activation of menstrual blood by male semen. “Sex” he wrote “is determined by the male principle already contained in the semen. If this is not strong enough, then the opposite must necessarily come into existence, and the opposite of man is woman.”

Being unable to study the internal structure of the human body, Aristotle turned to the study of animals, founding the science of comparative anatomy. He is said to have dissected over 50 different species, writing: “The inner parts of man are uncertain and unknown, wherefore we must consider those parts of other animals which bear any similarity to those of man.” For his embryological studies he used the chick embryo, describing among other observations the first sign of the embryo, the early development of the heart and great vessels, the beating of the embryo’s heart, and the differences between arteries and veins.

In Aristotle’s day, midwifery was the undisputed province of the midwives, though it was common practice for them to seek assistance from a doctor. Midwives had to be mothers who were past the age of childbearing. One of their functions was to advise men on which girls would be likely to produce the best offspring. They undertook vaginal examinations and were allowed to prescribe drugs, to procure abortion, and to bring on birth prematurely. Another duty was to show the newborn baby to the father. If he was then prepared to recognise the child as his own, he lifted it up for a moment and then handed it back to the midwife. Perhaps their most important responsibility, though, was on when and how to cut the umbilical cord. This was usually delayed until after the afterbirth had been expelled. Any delay in delivery of the placenta was managed by tying weights to the cord and by giving the woman powders to make her sneeze violently.

On birth

“It is natural for other animals also to be born head foremost, but children have their hands pressed against their sides. Directly they come forth they cry out and bring their hands to their mouth. There is evacuation of excrement sometimes at once, sometimes soon, but always within the day, and this excrement is more than accords with the bulk of the child. Women call it meconium; its colour is like blood and it is extremely black and like pitch but after this it already assumes the milk‐like character for the infant draws the breast at once.”

On maternal posture during childbirth

“The woman should lie on her back having her body in a convenient posture. That is, her head and breast a little raised so that she be between lying and sitting. For being so placed she is best capable of breathing and likewise would have more strength to bear her pains than if she lay otherwise …”

On ligation of the umbilical cord

“The division of the cord is the province of the nurse and requires an intelligence that does not blunder, for she must be able not only to give assistance by her dexterity in the difficulty of women’s labour but also must be quick‐witted for emergencies, also in the matter of tying the cord for the child. For if the afterbirth is passed at the same time let the cord be tied, away from the afterbirth, with a fillet of wool and it is then cut off from the part above: where it has been tied it grows together and the adjoining part falls off. If the knot comes undone the infant dies of haemorrhage. When the afterbirth does not come away at once but remains inside when the infant is outside, the cord is tied and division made.”

On resuscitation

“Frequently the child appears to be born dead, when it is feeble and when, before the tying of the cord, a flux of blood occurs into the cord and adjacent parts. Some nurses who have already acquired skill squeeze (the blood) back out of the cord (into the child’s body) and at once the baby, who had previously been as if drained of blood, comes to life again.”

On crying

“The infant does not cry before it comes forth, even if owing to difficulty of labour the woman succeeds in expelling the head but retains the rest of the body inside … Babies after birth for the first forty days do not laugh or cry when awake, but at night they sometimes do both. Even if tickled they do not usually notice it. Most of the time they sleep, but as they grow they keep changing in the direction of more wakefulness. It is evident that they dream but it is a long while before they remember their dreams …”

On lactation

“Women continue to have milk until their next conception; and then the milk stops coming and goes dry, alike in the human species and in the quadrupedal vivipara. So long as there is a flow of milk the menstrual discharges do not take place as a general rule, though the discharge has been known to occur during the period of suckling.”

On neonatal mortality

“Most of the babies are carried off before the seventh day that is why they give the child its name then, as they have more confidence by that time in its survival.”

On maternal love

“This is the reason why mothers are move devoted to their children than fathers: it is that they suffer more in giving them birth and are more certain that they are their own.”

On abortion

“As to the exposure of children, let there be a law that no deformed child shall live. However, let no child be exposed because of excess population, but when couples have too many children, let abortions be procured before sense and life have begun.”

Aristotle was below average height. Sharp and keen of countenance, he was blessed with boundless energy. He was always on the move and collected information from every source. A practical man and a careful observer, he not only sought facts but also methods on how to handle them and put them in order, setting the stage for the development of the scientific method many centuries later. He was high minded and kind hearted and devoted to his family and friends. Calm and without passion he was said to be fair to his enemies and rivals, grateful to his benefactors, and was in fact the embodiment of the moral ideals outlined in his ethical treatises. The following aphorisms on courage reflect some of his own philosophy: “The ideal man bears the accidents of life with dignity and grace, making the best of circumstances.” “Courage is the first of human qualities because it is the quality which guarantees the others.” “I count him braver who overcomes his desires than him who conquers his enemies; for the hardest victory is over self.” “Dignity consists not in possessing honours, but in the consciousness that we deserve them.”

Let me end with a thought from Aristotle that resonates with respect to the present state of our national health service, dominated as it is nowadays by politicians and managers. He wrote: “Each man judges well the things he knows and of these he is a good judge. And so the man who has been educated in a subject is a good judge of that subject.”