by Karen Maezen Miller: The pond in her garden isn’t like those decorating fancy homes and magazine covers…

In time, however, Karen Maezen Miller discovers the right view of her muddy waters: they’re not always pretty, but they are beautiful.

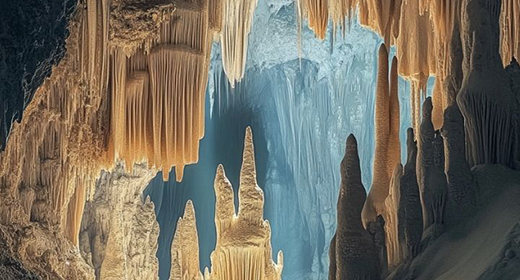

May we exist in muddy water with purity like the lotus.

— Meal Gatha

We weren’t doing the work all by ourselves. We had a yard guy.

The yard guy introduced us to a tree guy, and the tree guy suggested a sprinkler guy. The sprinkler guy knew a fertilizer guy whose brother-in-law was a fence guy. Before we did anything, though, we talked to a Japanese garden guy and asked him what we should do.

He said, “Spend twenty thousand dollars.”

That wasn’t going to happen. Not for a long while.

The cost of real estate in California can render anyone poor. We had been lucky to get in at the bottom of the market, buying the house for a little more than half of what it had sold for ten years earlier. But it was still a squeeze, and my prospects for work seemed slim. With twenty years of experience, I was overqualified for the few jobs out there and underqualified for the job right here.

This was upsetting. I thought I knew how to get things done, but I was at ground zero and already over my head. The roof needed replacing and the house needed to be repainted. There were creeping signs that the shower stall leaked. The air conditioner broke on a day when it was 115 degrees. I knew everything was old, but did it have to be so old ? Neither was the garden quite what it looked like on that first innocent encounter when we’d viewed the house with the real estate agent. Junipers had been left to wither, their arms outstretched in rigor mortis. Aging azaleas had massed into a thicket of nearly bare branches. The pruning had been botched. The hardiest plants were ones that weren’t supposed to be in a Japanese garden at all. Here and there were the errors of someone’s misguided intentions—a Mexican palm, a pink rose bush, a baby apple tree. In our eyes, the offenses kept growing.

People gave us picture books about dreamy Japanese gardens, and we tormented ourselves with comparisons to the gems of Kyoto. My husband bought flats of delicate mosses at the nursery. He tried to coax them into our sandy topsoil. But the sun was too hot and the irrigation too uneven. It took two or three tries before we conceded. What was it exactly that made a garden Japanese? We decided it wasn’t us.

Like the ocean to the earth, ponds covered three-fourths of the backyard. So we let the horticulture go for now and decided that what we really needed was a pond guy. The fish guy referred us.

We took him into the backyard and waited for the diagnosis. He walked the circumference of the ponds, inspecting the waterfalls and the pump-activated stream that fed them. He stood back to get a sense of it all. He kneeled low to peer into the water. He put his hands on his hips and asked, “What did you say your problem was?”

We answered, “They’re muddy.”

Ponds are the heart of a Japanese garden, or so the literature told us. Kato, the long-dead landscaper, shaped the four interconnected ponds into the form of the kanji character for heart, after the pond in an eighth-century temple garden in Kyoto. I wouldn’t recognize a kanji character if it was tattooed on my ankle, let alone shaped out of a puddle on the ground. Looking at the ponds all day through my kitchen window, I couldn’t see any semblance of it. Of course I understood that water really was the heart of things—the essence of life. At least on this plane of existence, water is life’s source and sustenance.

The problem is what we put into it. Everything ended up in this water: leaves, seed pods, and branches from the messy sycamores; acorns and pollen from the oak; pine and cypress needles; redwood bark, bamboo leaves, palm fronds, spent blooms, mosquito larvae, tadpoles, turtles, bird feathers, fish poop, and virtually anything that could be loosened by the gusting easterly winds. (Everything can be loosened by the gusting winds in this part of California.) A family of raccoons romped in the water nightly, dining on frogs and koi and leaving parts behind. One morning the tables turned, and we had to fish a raccoon out of the pond. It had expired from some unknown cause in the night, a reminder of how little we knew about what was happening under our noses. Traces of these—and other mystery ingredients—would stagnate, sink, and ferment into the thick sediment at the bottom.

Our ponds were muddy. The water was an ugly brown, laced with bright green strings of algae. It didn’t look like any koi pond we’d seen in a better homes magazine. We thought it was sick, and that the few fish swimming in the murk must be terribly sick too.

“This is the most perfect example of a naturally purified pond that I’ve ever seen,” the guy finally said. He was awestruck.

Then he showed us the hidden elegance in the whole rotten mess. The large surface area supplied ample oxygen. The stream and waterfalls were natural filters. The mud balanced the water’s chemistry, keeping plants and fish alive. The algae was seasonal, triggered by temperature changes, and easy to manage. The precise science of pond scum was beyond my grasp, but the bottom line was this: ours wasn’t like the designer fishponds decorating fancy homes and magazine covers. This was the real deal. It would always be trouble—ponds are a shitload of trouble—but it wasn’t a problem. Skim the leaves. Circulate the water down the stream and falls. Let the mud settle, and the pond will purify itself.

He didn’t do anything that day—except give us the right view of the water. It isn’t always pretty, but it’s beautiful.

We never needed to call him again.

In Japanese there is a single word that means “heart, mind, and spirit”: shin. Japanese is not like English, in which we divide into opposing concepts things that actually share the same indefinable essence. Like the ponds in my backyard: they look separate but are interconnected. Open the tap at the source, and the water from one pool swells into the other. Soon the illusion of separation disappears. The fish come to the surface and leap.

The word for a Zen retreat is sesshin, which means “unifying the mind.” Ironically, Zen types argue about the meaning of the word, which is also defined as “gathering the mind” or “touching the mind.” The differences don’t matter. In the actual doing, the definitions of sesshin blend into one true thing: your life right here and now.

The mind we bring to a retreat is marvelous and fully functioning. As with water, the problem is what we put into it. The debris of old pain and resentments. The weight of grief and loneliness. The cloud of judgments. The poison of jealousy and anger. The anxious, internal rat-a-tat-tat pelting the present calm like a storm of stones. Buddha called these kinds of disturbances “upside-down thinking.” By the time we come to sesshin, we feel as if we are drowning in a muddy flood, unable to breathe, see, or slow down. We can’t imagine the deep stillness that lies beneath the waves.

A pond doctor enters the room with a reassuring smile and says, “You are a perfect example of natural purification.” His medicine is nothing more than zazen, the way of sitting. He reminds you that you can inhale an infinite supply of oxygen without mechanical intervention. He tells you to follow the movement of your breath to clear distractions, and use your own senses to refresh your awareness. Naturally, disturbances occur, but you can right yourself again. Sit still, just sit still and let the mud sink to the bottom. Your life rises up on a sturdy stalk and blooms on the surface like a lotus flower.

What goes into sitting isn’t pretty, but after a while it becomes beautiful.

Now, what did you say your problem was?