by Ocean Robbins: By the middle of the 19th century, most scientists believed that they had solved all the important questions of nutrition…

We are proud to announce a new partnership with John and Ocean Robbins and the Food Revolution to bring our readers Summits, Seminars and Masterclasses on health, nutrition and Earth-Conscious living.

Sign Up Today For the Healthy Brain Masterclass

After all, they’d discovered the building blocks of matter — atoms and molecules — and everything else was just details.

The acknowledged “Father of Nutrition and Chemistry,” Antoine Lavoisier, had figured out in the 1770s that food was a kind of energy, and our bodies were engines that ran on that energy when supplied in sufficient quantities. Further observation and experimentation identified the key elements involved in metabolism — carbon, hydrogen, nitrogen, and oxygen — as well as the macronutrients composed of those elements — carbohydrates, fats, and proteins.

All that was needed, so the thinking went, was to process ingredients into “purified foods” that contained the perfect macronutrient ratios. Then all animals, including humans, could eat completely optimized diets. That was the theory, anyway.

In the real world, things were not that clear-cut. Sailors grew exhausted, bled spontaneously, and developed debilitating leg pains even when supplied with plenty of hardtack (a dense biscuit made from water, flour, and salt) and other preserved foods on long voyages. Previously healthy dogs whose diets were switched to only sugar would sicken and die within a month, despite getting plenty of calories. Researchers at the University of Wisconsin didn’t understand why dairy cows fed wheat grew blind and stunted and couldn’t reproduce, while their sisters who consumed corn did just fine.

Something was missing — but what?

Researchers from around the globe applied themselves to solve the mystery. And the first ones to identify a chemical that wasn’t a macronutrient but was still necessary for mammalian survival took on the dairy cow conundrum. Elmer Vernon McCollum and his assistant, Marguerite Davis, had the idea to test their nutritional theories on rats first, before moving on to bovine subjects. (Our view on the use of animals in medical research is here.)

They fed rats one of three foods — milk fat, olive oil, or lard. Only the milk-fed rats thrived, leading McCollum and Davis to conclude that not all fats were alike. Further exploration led to the realization that adding extracts of milk to the olive oil and lard created a substance that could also sustain the rats. So it was something in the milk fat that made the difference.

That mystery chemical was misnamed “Vitamine” as a portmanteau of “vital” (which it was) and “amino acid” (which it wasn’t). The Wisconsin dairy industry was thrilled to market to the world that this newly discovered substance, which was absolutely crucial to life, came from cow’s milk. The fact that cows access it the same way humans do, via plants, was not considered convenient to the marketing of dairy so it was left out. There was no powerful leafy greens lobby to run with that story — and there still isn’t.

Today, vitamin A continues to be touted as the vitamin we get from animal products, when in fact it originates from many plant sources. In this article, we’ll look at this alphabetically premier nutrient — what it does, where to get it, and how much you need.

What is Vitamin A?

Vitamin A is, along with vitamin D, vitamin E, and vitamin K, a fat-soluble vitamin. It accumulates and is stored in the body (organs and tissues) for later use, which is important because this feature of such vitamins means it’s possible to get too much of them. This contrasts with water-soluble vitamins like vitamin C and the B vitamins, which the body excretes once it has used all it needs.

Vitamin A has antioxidant properties (you’ll learn why I didn’t write “is an antioxidant” below), and is also important for healthy vision, growth, cell division, reproduction, cellular health, and immunity. It originates in a wide array of plant foods, such as leafy green vegetables and orange and yellow fruits and veggies.

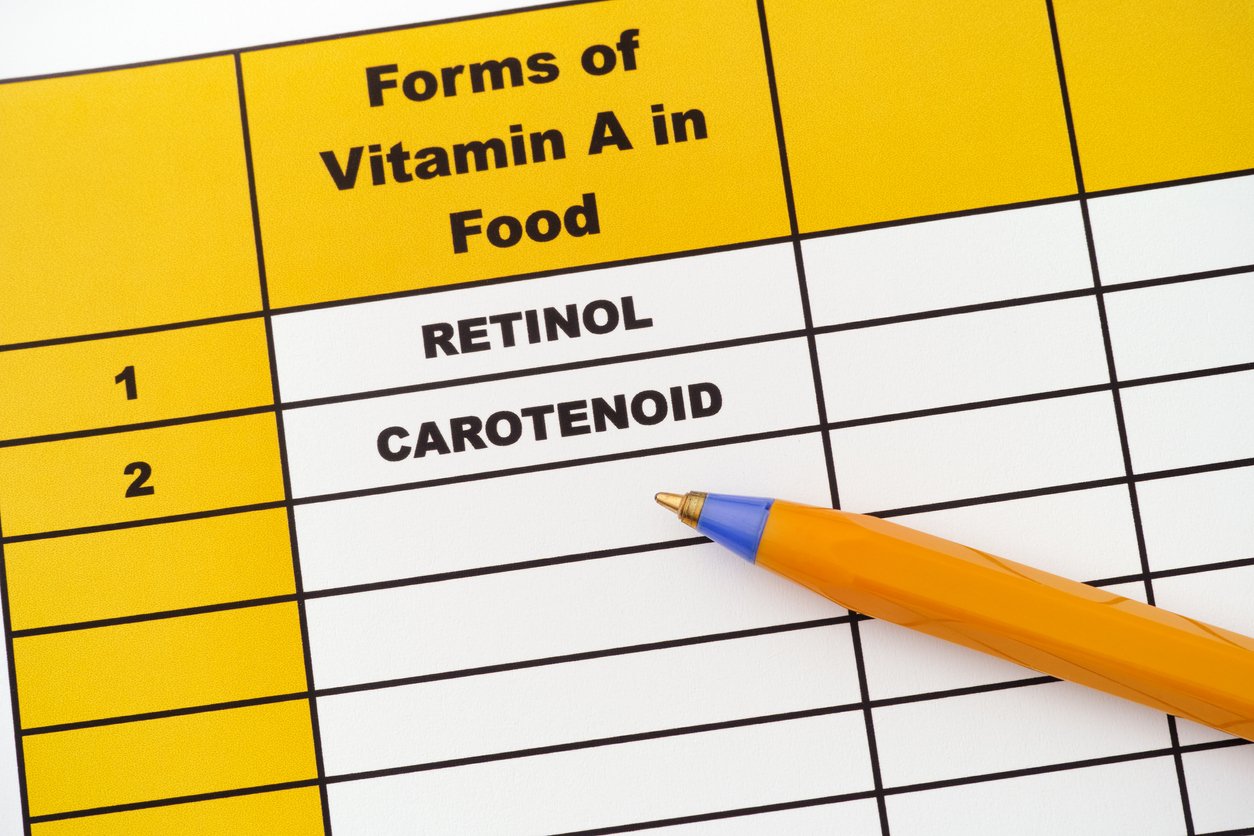

Types of Vitamin A

As nutritional biochemistry marched on, it became clear that no single vitamin A exists. Instead, it’s a generic term for a group of fat-soluble compounds that include retinol, retinal, and retinyl esters.

As mentioned, it originates in plant foods. Animals — including humans — eat plants that contain vitamin A precursors, which are then converted into one of the three active forms of the vitamin. So you can get already synthesized vitamin A from meat, fish, poultry, and dairy, in the form of retinol and retinyl esters. And you can also get the precursors from plant foods (provitamin A carotenoids, in case you’re about to go on Jeopardy! and suspect that one of your categories will be “Forms of Vitamin A”), and let your body convert them into an active form of the vitamin.

To further prepare you for vitamin A Jeopardy!, some of the most common plant-based carotenoids are named alpha-carotene, beta-carotene, and beta-cryptoxanthin.

If all this is going in one ear and out the other, don’t worry: Your body knows exactly what all the chemicals look like and what to do with them. Even if you can’t tell the difference between retinol, retinal, and retinyl, your body takes care of all these compounds inside your digestive tract. It knows what to keep and what to excrete, what to convert and what to leave alone.

Spoiler alert: It’s widely believed that vegans are at risk for vitamin A deficiency. But that belief happens to be wrong — as long as vegans eat a variety of fruits and vegetables, and include sources of carotenoids such as sweet potatoes, squash, or carrots in their daily diets. Apricots, cantaloupe, and leafy greens like spinach and kale also provide good amounts of carotenoids.

Side note: there are other carotenoids in foods, including lycopene, lutein, and zeaxanthin that are not converted into vitamin A and are therefore referred to as non-provitamin A carotenoids. While they offer other important health benefits, they don’t have any vitamin A activity.

Most of the vitamin A in your body is stored in your liver as retinyl esters. These are then broken down into what’s called all-trans-retinol, which binds to retinol-binding protein. After that, it enters your bloodstream so your body can use it.

How Much Vitamin A do You Need?

The US Recommended Dietary Allowance (RDA) for vitamin A is 900 micrograms (mcg) for adult men and 700 mcg for adult women. This begs the question, micrograms of what?

Because the body can handle so many different kinds of vitamin A and its precursors, RDAs for vitamin A are given as retinol activity equivalents (RAE), an accounting trick to help us compare the proverbial apples and oranges (in this case, carrots and kale).

Most people get enough from their diet, which is a good thing, because it’s really hard to measure the actual amount of vitamin A in our bodies. Labs typically measure blood plasma or serum levels of retinol and carotenoids because blood samples are easy to collect.

The problem is, blood levels are not always reliable indicators of vitamin A status because they don’t decline until vitamin A levels in the liver and other storage sites are almost depleted and because acute and chronic infections can decrease serum and plasma retinol concentrations.

If you’re concerned about your vitamin A levels, the most accurate way to assess them would be to measure your vitamin A liver reserves. Unfortunately, the most reliable way to do this is to biopsy your liver, which is highly invasive and therefore rarely done. Fortunately, there’s another method, called retinol isotope dilution, that is just about as accurate as biopsy. In that test, you’re given a small amount of “labeled” vitamin A (not radioactive — you won’t glow in the dark after ingesting) that mixes with your regular vitamin A for a couple of weeks, after which the ratio of labeled to unlabeled vitamin A is measured using mass spectrometry, which if you understand you should probably have won a Nobel Prize in Physics by now.

Vitamin A Benefits

Eye Health

The fact that Bugs Bunny never wears glasses has a scientific basis, apparently. Legend has it that Bugs Bunny eats a lot of carrots, which are an abundant source of (drumroll please…) carotenoids. Sufficient vitamin A stores may protect your eyes against age-related eye disease and help maintain normal night vision. Vitamin A is needed to convert the light that enters your eye into a signal sent to your brain. The active form of the vitamin, retinal, combines with a protein called opsin to form rhodopsin, which is found in the retina and is sensitive to light.

In fact, one of the first symptoms of vitamin A deficiency can be night blindness, a condition in which sufferers retain the ability to see during the day but experience reduced vision in low light.

Vitamin A also helps protect the cornea (the outermost layer of your eye) and the conjunctiva (the thin surface that covers your eyeball and the insides of your eyelids). Along with other carotenoids, vitamin A appears to help prevent age-related macular degeneration (AMD), which is the leading cause of blindness around the world. One long-term study of more than 100,000 subjects found that having higher amounts of carotenoids in the blood is associated with up to a 25% lower risk for AMD, replicating the findings of a 2001 randomized clinical trial run by the National Eye Institute.

Immune Support

Vitamin A triggers immune responses that help protect your body from infection and illnesses. It’s also involved in the creation of T cells and B cells, which are key players in the immune system and can thereby help your body fight infections. Low levels of vitamin A can actually increase the presence of pro-inflammatory compounds in your body — substances that work against the ability of your immune system to function well. It’s also important for wound healing, via its ability to enhance collagen production and skin repair.

Antioxidant Activity

Technically, oxidation means that an atom or molecule loses electrons during a chemical reaction. While this may not sound all that bad (I mean, there are plenty of electrons to go around, I assume), oxidation generally means some kind of wearing down or corrosion. Rusting metal is undergoing oxidation. And in your body, oxidation often comes in the form of free radical damage (those errant electrons causing havoc) that can increase your risk of a number of chronic diseases, including heart disease, cancer, diabetes, and cognitive decline.

Nutritional biochemists have argued for decades about whether vitamin A is an antioxidant. On the one hand, the vitamin does appear to enhance antioxidant activity in the body. On the other hand, it doesn’t behave like an antioxidant, and appears to affect the body by turning particular genes on and off. Recent research suggests that vitamin A is an “indirect” antioxidant, working to help regulate genes involved in the body’s antioxidant responses and helping to protect your cells from oxidative/free radical damage.

Diets high in carotenoids have been shown to be associated with a reduced risk for diseases like lung cancer, heart disease, and diabetes.

Reproductive and Fetal Health

Vitamin A is essential for both male and female reproductive development. Specifically, it’s needed for healthy sperm production and egg development. Getting enough vitamin A is critical during pregnancy for the health and development of the placenta, as well as fetal tissue development and growth.

Vitamin A deficiency is a public health issue for pregnant women in most developing countries. One study recommended public health programs to supplement nutrients like vitamin A in men and women of reproductive age in order to prevent fertility problems.

Potential Downsides of Vitamin A

Because vitamin A is fat-soluble and accumulates in the body, it’s possible to overdose on it, especially on preformed vitamin A from animal sources and from supplemental vitamin A. That’s why it’s generally advised to prioritize vitamin A from whole-food plant sources. Higher doses of supplemental vitamin A are not recommended for most people unless directed and supervised by your health care practitioner for a medical reason.

Acute vitamin A toxicity, also referred to as hypervitaminosis A, can show up days or weeks after someone ingests more than 100 times the RDA. Symptoms can include nausea, vomiting, vertigo, blurry vision, bone thinning, liver damage, headache, diarrhea, joint pain, skin irritation, and birth defects (when taken by pregnant women). If the overdosing continues for a prolonged period, it can even prove fatal.

While overzealous supplementation is the main danger, it’s also possible to consume too much preformed vitamin A from animal-derived foods. In particular, liver is a concentrated source, since, as we’ve seen, that’s where mammalian bodies store their vitamin A.

To prevent the possibility of hypervitaminosis A, it’s recommended that adults should not exceed 10,000 IU (3,000 mcg) per day.

What about those carrots and leafy greens? The good news is, you’re not likely to end up with too much Vitamin A from overdoing it on precursor-rich plants, thanks to a slow conversion process. Your skin, however — typically the palms of your hands, soles of your feet, and even your nose — can turn orange if you consume huge quantities of carrots and other orange-yellow vegetables, for example via drinking quarts of carrot juice a day. While potentially alarming, this condition, known as “carotenosis,” is not considered dangerous, and generally resolves once the carrot-tinted individual cuts back on the orange stuff.

If you supplement with vitamin A (even in the form of a multivitamin), be aware that the nutrient can interact with many medications, including anticoagulants like Warfarin, topical cancer drugs, certain weight loss drugs, and many others.

Vitamin A Deficiency

True vitamin A deficiency is rare among financially sufficient people in industrialized countries, but can be widespread in countries where access to/intake of vitamin A-rich foods is low. It’s a serious condition — according to the World Health Organization, insufficient vitamin A is the leading global cause of preventable blindness among children. Fortunately, when vitamin A deficient populations are able to grow carrots, squash, sweet potatoes, and other orange and green veggies, the incidence of blindness drops dramatically.

Because of its role in regulating the immune system, vitamin A deficiency also increases the risk of death from diarrhea, gastrointestinal infection, and measles. Even in the United States, children living in poverty, who may subsist on “calorie-dense and nutrient-poor” diets, can suffer from insufficiency and deficiency that predisposes them to infectious diseases like influenza.

Other groups at higher risk for vitamin A deficiency include pregnant/breastfeeding women who live in developing countries, individuals with cystic fibrosis or GI disorders, and premature infants.

Where to Find Vitamin A

While vitamin A is found in a wide array of animal-derived foods, like eggs, meat (especially liver), and dairy, these sources come with ethical, environmental, and health concerns. Fortunately, you don’t need to consume any animal-based foods to get all the vitamin A you need. Plants have got you covered.

Bearing in mind that the recommended adult dose is 900 mcg for men and 700 mcg for women, check out how easy it is to reach those amounts by eating a varied (and delicious) plant-based diet:

- Carrots: 1 medium carrot (509 mcg)

- Spinach: 1 cup leaves (141 mcg)

- Cantaloupe: 1 cup cubed (270 mcg)

- Mango: 1 cup diced (89.1 mcg)

- Sweet potatoes: 1 medium without skin (1,190 mcg — ding ding ding we have a winner!)

- Kale: 1 cup (50.6 mcg)

- Pumpkin: ½ cup canned (955 mcg)

- Collard greens: 1 cup raw (90.4 mcg)

- Red, orange, and yellow bell peppers: 1 medium sweet red pepper (187 mcg)

- Papaya: 1 small (73.8 mcg)

Most multivitamins contain some vitamin A. If you take one, check the label to see how much it contains per serving. If you’re rocking the vitamin-A rich fruits and vegetables, you may want to switch to a multivitamin that doesn’t contain added vitamin A. Of course, check with your health care professional to make sure your unique needs are met.

Plant-Based Vitamin A Recipes

Now that you’ve learned it’s easy for your body to make plenty of Vitamin A from its source — carotenoid-rich plant foods — are you excited to try out some yummy recipes? If you’re looking for one to help support your eye health be sure to try out the Autumn Sunrise Smoothie. Curious about foods that will support and optimize immune function? You can’t go wrong with the Rainbow Salad with Carrot Ginger Dressing. Or do you simply want to discover new and tasty ways to incorporate the mighty sweet potato? Then Buckwheat Sweet Potato Chili is the perfect weeknight meal for you and the entire family! No matter which recipe you choose, we hope you enjoy some of these wholesome ways to get your vitamin A.

1. Autumn Sunrise Smoothie

The Autumn Sunrise Smoothie may be the tastiest, easiest, and prettiest way to obtain your daily vitamin A! Carrots and mangoes provide a good source of vitamin A in the form of beta-carotene. Beta-carotene is abundant in yellow, orange, and dark green leafy plant foods. No wonder they come with a host of benefits! This gorgeous smoothie can help support immune and reproductive health, protect your eyes and heart, and make your skin look and feel rejuvenated — all thanks to vitamin A (along with a few other fabulous nutrients).

2. Rainbow Salad with Carrot Ginger Dressing

Looking for a recipe that will pack a vitamin A punch? Well, look no further! Rainbow Salad with Carrot Ginger Dressing is a delicious (and nutrient diverse) meal that provides an unexpected vitamin A source from kale. Although green and unassuming, this beloved veggie is a potent source of beta-carotene with around 50 mcg per cup. When paired with bright orange shredded carrots, as well as this delightfully sweet and savory Carrot Ginger Dressing, you could get approximately 800 mcg of vitamin A — just about the entire amount you need in a day. This dish sure sounds like a vitamin A winner to us!

3. Buckwheat Sweet Potato Chili

Sweet potatoes are one of the richest sources of plant-based vitamin A. They contain a whopping 1,190 mcg of beta-carotene from just one medium-sized sweet potato. Sweet potatoes are a versatile food that delivers a delicate and sweet taste, which makes them an excellent addition to many savory (or sweet!) dishes. Our Buckwheat Sweet Potato Chili is a comforting bowl of deliciousness that is packed with vitamin A (beta-carotene), B6, potassium, fiber, and vitamin C. The best part is this dish only requires chopping some veggies before adding all of the ingredients to one pot or a slow cooker.

Conclusion

Vitamin A is a fat-soluble vitamin that you can source from many plant and animal foods, as well as in supplemental form. And, just as certain other animals, like cows, convert plant-based Vitamin A precursors into their active forms, so do humans. Eating carotenoid-rich plants gives you the best of both worlds — adequate vitamin A intake, which is essential for healthy immune function, eye health and vision, fertility, and reproductive health; and, the ability to prevent potential vitamin A overdose and toxicity.

True vitamin A deficiency is rare in healthy people who eat enough food and a varied diet. Vitamin A supplementation, especially in high doses, is generally not recommended due to the potential for toxicity, interactions with medications, and the fact that most people get enough through food. Incorporating plenty of whole plant foods into your diet, like dark leafy greens and red, orange, and yellow fruits and vegetables, is a great way to get vitamin A.