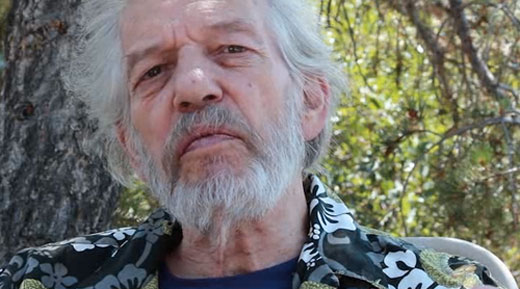

Stephen Levine: interviewed by Tom Ferguson MD: Many people think that if they came down with a fatal illness, they’d react by

grabbing a giant bottle of whiskey and an attractive sexual partner and spending their remaining time at the nearest warm beach.

But in working with thousands of dying people, we’ve found that virtually no one does that.

What people do is to begin looking into their own hearts and into the eyes of those with whom they share their lives. And all too often they find that these aren’t places they’ve looked very deeply before.

Fred

We just spend some time with Fred, a 54-year old bus driver for Greyhound. After Fred’s diagnosis of terminal cancer, he and his family decided that he would prefer to die at home.

Because of his work, Fred had spent most of his married life away from home. He’d never had a very close relationship with his children. He and his wife had dealt with most major family difficulties — including some severe sexual problems — by totally ignoring them. Fred had always felt he needed to keep up a macho image, and his wife felt trapped in her role as wife and mother. His children only used the house as a place to eat and sleep.

But as his disease progressed, Fred reached the point where he could no longer play his accustomed roles. He couldn’t be a tough guy any more. He had a lot of pain, and all the members of his family has to work like hell to take care of him. His teenage son — whom he formerly hardly spoke to — was now giving him baths and rubbing his back. His daughter would read to him when he had trouble sleeping.

As Fred’s cancer progressed, he and his family broke through one barrier after another. It wasn’t easy, but through it all the family members drew closer and closer. Everyone in the house learned to trust and confide in each other. Neighbors who came to visit would tell us, “I expected to find a house of death. Instead I find a house of life and love. This family has never been as close as they are now.”

In observing the changes in Fred’s family, we were reminded of the thousands of Brahma bulls that wander around India. They’re considered sacred. If two men are trying to kill each other with knives, and a Brahma bull walks between them, they’ll pull their knives away, because they mustn’t scratch the bull.

Dying people are like Brahma bulls. In their presence, so many of our petty hassles are simply forgotten. We realize what’s impermanent, and what’s of permanent value.

For most of the people we’ve worked with, the diagnosis of a fatal disease comes as a frightening experience. One of their most frequent comments is: “I feel like I’ve wasted my life.” So much of who they are has been held back. So much of their precious time was spent running away from their fears, waiting for the future, or remembering the past.

So little of their lives was spent actually living. Although they’ve been alive 40, 60 or 80 years, it suddenly feels to them as if they’ve hardly lived at all. They’ve been so buy striving for security and trying to live up to one ideal or another that they forgot to taste and savor the texture of their lives. They were so busy making a home, building their career, becoming solid citizens, that they forgot to live.

Daren

We shared some time recently with Daren, a 38-year-old Los Angeles man dying from a degenerative nerve disease. Two years ago Daren was handsome, successful, and vibrantly health. He had reached the pinnacle of professional success. he was a singer, dancer, and virtuoso guitarist, and was greatly sought after by many for the major Hollywood studios. He had a wife and two children, a lovely home, and ran five miles a day.

Today Daren is strapped to a wheelchair, unable to support his own body’s weight. His lungs are so weak that he must consciously draw in enough air to make his vocal cords work. He can no long move his arms, legs or body. He needs help to go to the bathroom. His flesh is slowly melting away from his bones.

At first Daren was in agony because he couldn’t play, couldn’t dance, couldn’t earn money, couldn’t drive his new Mercedes, couldn’t make love — in short, he could no longer live up to his models of who the thought he should be. But after a time, he began to see that it was not his illness that was the problem.

“It was those damn models,” he realized. “Those models were always a hassle for me. They’re like balloons with holes in them — I’ve had to keep puffing and puffing all the time to keep them from collapsing. They’re not really who I am.” And gradually he’s been able to let go of his identification with his models.

One day we were sitting and talking and he said to us, ‘You know, I’ve never felt so alive in my whole life. I can see now how all the things I used to do to ‘be somebody’ actually separated me from really being alive. For all my outward success, my life back then was just a sort of busy, numb dullness.”

He laughed and shook his head. “We’re such fools, aren’t we? We spend so much time polishing our personalities, strengthening our bodies, keeping up our social positions, trying to achieve this and that. We make such serious business of it all. But now that I can no longer do the things I thought were so important, I have so much love for so many things. I’m discovering a place inside I’d never looked at, never knew. None of the praise I received in the world brought me half the satisfaction I experience right now from just being.”

Few Well Prepared for Death

Very few of the people we see are well prepared for their deaths, and no wonder. We are taught to keep thoughts of death out of our consciousness, ignore illness, to do our best to disguise the natural changes of aging. We grow up believing — and teaching our children — that we are not supposed to suffer. We are not supposed to grow old. We are not supposed to experience loss or pain.

We end up carrying a heavy load — a great deal of fear of illness and death. When Ondrea had cancer, people were afraid to visit her. They were afraid to touch her. And if they did come, they were terrified.

The Pepsi Generation

One of the things we can learn from the dying is simply that it’s all right to die. It’s all right to be ill. It’s OK to be in pain. Sometimes we’ll be working with a group of cancer patients, we’ll say, “You know, it’s OK that you’re suffering. It’s OK to suffer.” And there’ll be a lot of shocked looks, like it has never occurred to them that it really could be OK.

It’s the American way to be hale and hearty, and it’s very difficult for us to accept the fact that illness and death are a normal part of life. Everyone in the Pepsi generation must grow old and suffer and die just like all previous generations. But our conditioning makes it very hard to accept that.

It’s hard for us to accept situations in which we are unable to live up to our models of what’s OK. Elizabeth Kubler-Ross used to say that someday she would like to write a book titled I’m Not OK and You’re Not OK and That’s OK.

We learn to work hard to be OK — whatever that means for us. The dying can teach us a great deal about the ways we learn to distort ourselves, to diminish ourselves, to reshape ourselves in order to conform to that OK model, how we are raised to be constantly posturing, constantly inventing an acceptable reality.

A Mosaic of Awareness

The ebb and flow of our awareness is like a complex mosaic made up of many tiles. But because we learn that some of those tiles — parts of ourselves — are considered unacceptable, we begin, at a very early age, to pick out — or cover up — the offending tiles: “Oh, no, I’m not supposed to be angry,” so we take that tile away. “That part of my mind is too crazy for anybody to see.” So we cover it up. “Oh, God, I don’t want anybody to see my hatred. Or my jealousy. Or my confusion. Or my greed. Or my envy. That self-hatred, that guilt — that can’t be who I really am. That’s bad. That’s unacceptable. That’s crazy. That’s neurotic.” So out they go, until what is left is a pale caricature of who we really are. But the dying tell us that is who we really are — that continually changing flow of thoughts, those conflicts in values, that continual confusion and not knowing. This is our life.

Accepting “Unacceptable” Feelings

The dying teach us that because of our efforts to drive those “unacceptable” feelings out of consciousness, we end up wondering if we have ever really lived. They teach that it is better to sit quietly with our unwanted states of mind, to accept the pain, accept the waves of unfashionable feelings, to accept our own confusion — rather than to let these painful events drive us out of awareness, into defenses that pull us away from life.

Perhaps the greatest gift the dying have to offer is the realization that we need not wait until we receive a terminal diagnosis to begin to relax our attachments to our images of who we think we should be. How much better, they tell us, to realize that we are not our fears, not our confusion, not our defenses. That it is possible to let those states of mind flow through us without identifying with them, without holding onto to them, simply doing our best to stay open to awareness.

They teach us that it is possible to let whatever needs to happen, happen — without being driven into the life-denying reactions our fears would lead us to. It is possible to experience it all, to be threatened by nothing, to withdraw from nothing, not even death.

Learning to be Substantial

We are taught to make ourselves substantial, to take on certain roles and play them with utmost seriousness, to be responsible members of society. The dying teach us that we must live more lightly, take ourselves less seriously, accept our own impermanence, our own no-knowing. Not to harden against life, but to soften into it. They teach us that real growth comes from coming to the edge of one’s model, then letting that model go, and seeing what comes next. The dying can teach us that it’s possible not to be “something” but just to be.

Thousands of years of meditation practice teach us that thinking in terms of “the mind” rather than “my mind” helps clarify what’s really happening. When you look at your flow of awareness as “my mind,” there’s confusion, because if it’s your mind, then you must be responsible for what’s in it. But when we look closely at our thought processes, we see that much of what arises in the mind is actually uninvited. We don’t invite guilt. We don’t invite anger. They come by themselves.

The Worst Possible Insult

Try this experiment: Think of the worst possible insult you can imagine, then suppose that you arrive home to find your living space broken into and that message scrawled across your wall. You would experience — involuntarily — a state of mind that you did not invite, expect, or want. Whose mind did that?

The mind is constantly rating us on our behavior, constantly comparing things as they are to imagined models of things “as they should be.” The mind finds everything wanting: us, others, and the world. It is never satisfied for long. Identification with the mind is the very definition of suffering.

To the extent that we identify with “my mind,” our lives will be in constant turmoil. We will be jerked up or down by any tray thought that drifts across our mind.

The dying teach us that to be able to accept ourselves in our true complexity, we must, without judgement, accept the craziness of the mind itself — accept it without mistaking it for who we really are.

Just Sleeping, Just Eating

For those of us who live in the mind, life is 99 percent an after-thought. It isn’t tasting, touching, smelling, loving, being alive; it’s mostly the mind thinking about what we are doing. An action occurs, and a moment later we think of ourselves as acting. We see a bird, and a moment later we are no longer seeing the bird, but thinking of ourselves looking at a bird. At other times we live in fantasies of the future or the past. If we start to experience our flow of consciousness as just the mind “doing its thing,” we find ourselves relating more directly to the world. It’s as though the mind, the “I” disappears, and there is just smelling, just dancing, just seeing the sunset, just sleeping, just eating our food, just being with someone we love.